All the lonely people/Where do they all come from?/All the lonely people/Where do they all belong?

Eleanor Rigby

The Beatles

When Imtiaz Ali was busy casting for his last film Tamasha (2015), the lead pair of Ranbir Kapoor and Deepika Padukone may have been an obvious choice for various reasons, but there was an element of surprise in the second half of the film. Vivek Mushran, who made his debut as the ‘Ilu Ilu’ boy in Saudagar (1991) with Dilip Kumar as his grandfather, played the role of a middle-aged boss to Ranbir. It was odd, yet nice to see Mushran on the big screen again. Once known for his boyish charm and his resemblance to Dev Anand, he essayed the part-funny, part-evil role of a tough boss with great ease. This at a time when his contemporaries are still playing leads in commercial hits.

In 1991, Mushran could not have asked for a better debut than with hit director Subhash Ghai, but he just trailed off after that, doing films like Prem Deewane (1992), Ram Jaane (1995) and Bewafa Sanam (1995). The Indian film industry, as any entertainment industry, is full of people like Mushran. Actors and directors who did one or two films, ruled the day while there was still light, and then vanished into the sunset. Some had a dream launch because of their family ties, like Kumar Gaurav and Esha Deol; some were handpicked—the Rahul Roy and Anu Agarwal pair in Aashiqui (1990), Gracy Singh in Lagaan (2001), Antara Mali in Company (2002), Gayatri Joshi in Swades (2004). The light-eyed Sneha Ullal, who got a big break against Salman Khan in Lucky (2005), and was noticed for her likeness to Aishwarya Rai, also failed to hold on to the hype. After Mani Ratnam’s hits Roja (1992) and Bombay (1995), the suave Tamil actor Arvind Swamy became the ideal husband every woman dreamed of. Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998) shot J.D. Chakravarthy, opposite Urmila Matondkar, to the moon. But soon after their promising debuts, both these actors faded out of public memory. Even in parallel cinema, actors like Chitrangada Singh, who debuted with Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005), struggled to deliver that kind of hit later in her career, despite the talent.

Imtiaz Ali, the director of Tamasha, chose Mushran over 10-12 actors, including those from NSD, through auditions. He believes this category of actors are “specially evolved” because of their journey. “He could portray the character so well also because he comes from north India and has seen such people. He could speak without any sense of tragedy. He was eager to learn and was enthusiastic. He said things might have been different if he had known what he knew about acting now. The journey to popularity may not always coincide with the journey of the actor,” says Ali.

“The audience doesn’t compare you to the first big film all the time,” says trade analyst Komal Nahta. “You got to shine in the other films. The point is your choice of films and delivering the goods. Public memory is short and they view each film afresh. The industry is so fickle, it’s all a matter of being at the right place at the right time with the right people.” Take Kumar Gaurav, who was the darling of the fans after the superhit Love Story (1981). “But he tried other genres and got exposed as an actor and didn’t stand out,” adds Nahta.

Among the directors, one who had a tremendous debut is Kundan Shah. The laugh riot Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron (1983) (JBDY) was made on a mere Rs 7-lakh budget with NFDC funds. It is a cult comedy to this day. Shah says that film became big much after its release. “It is difficult to say how it has survived. When anything becomes a cult, even mistakes are appreciated,” says Shah. “It was a novel way of treating humour and it was not just comedy for comedy’s sake. It has a larger cause but it was made in a vacuum. We were not bothered about the release because nothing got released those days. It was a mad script and I should thank the mad committee which passed it. Nonsense is most difficult to replicate, you see,” he adds. Shah remembers that he had no offers to direct films—except one that was then titled ‘Ek Phool, Char Kaante’—after JBDY’s release. He later made some memorable films such as Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa (1994) and Kya Kehna (2000), but then nothing seemed to match JBDY. His latest film, P Se PM Tak (2014), also tanked at the box office. “The critics dug my grave by comparing all films to my first film,” Shah says wryly. “They don’t realise it was a different wicket altogether when I was making the other films. Also, no one has shown interest in making a film similar to Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron in all these years.”

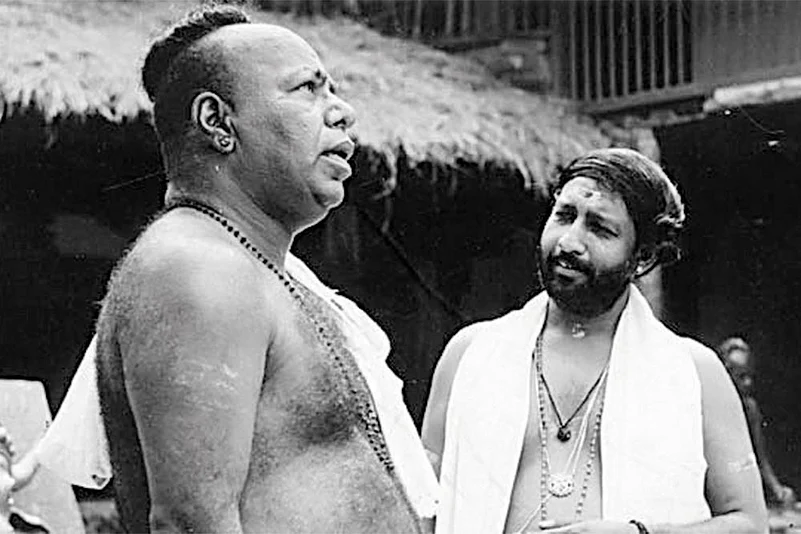

Even today, some of those who have experienced the award-winning Malayalam film Perumthachan (The Master Carpenter, 1991) are known to make that crazed journey to a remote village near Ochira, Kerala, to meet the film’s own master crafter, director Ajayan. His life has all the makings of a classic tragedy—the film that enthralled the world and won critical acclaim also saw the curtains down on his career. His brilliance seems to be entwined with a tragic flaw. What happened after his first film? “Perumthachan is fraught with tension. I was looking at perfection,” says Ajayan “Every scene in the film is dear to me. Actor Thilakan, the protagonist, had heart problems. In the scene where he had to kill his son, I got him to climb on top of the scaffolding. I couldn’t match its perfection.”

Today Ajayan, who is the son of Malayalam film director and playwright Thoppil Bhasi, is cocooned in his own memories and reluctant to engage with the outside world. He says there are two films that he wants to do—one is the autobiography of his father Ollivill Ormakkal (Hidden Memories) and the other is M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s novel Manikyakallu. “Manikyakallu was the first book I read completely and I have treasured it ever since. Even before I joined the Adyar Film Institute, I had stayed with director Bharathan for four to five years. I enjoyed working with Bharathan the most.”

Ajayan was a first rank holder from the Adyar Film Institute in Chennai. Following his success with Perumthachan, he got M.T. to write the script for Manikyakallu. He went abroad to study special effects to bring alive this children’s fantasy story, but it did not materialise even after four years. Though producers were initially interested in Ajayan doing the film, soon they distanced themselves for he was prone to excessive drinking and the desertion of producers caused him to slip into depression. Director Mohan, who has seen his work from the early ’70s says, “There is no one else in Malayalam cinema like him. He directed so brilliantly and then disappeared from the scene.” Ajayan still longs to direct Manikyakallu, which he says was what brought him to films in the first place. “There are actors like Asha Jayaram (Onnu Muthal Poojyam Vare, 1986) and Ramachandran (Novemberinte Nashtam, 1982) who acted in single films and then disappeared from cinema altogether. But nothing is as tragic as Ajayan’s story,” says film journalist Prema Manmadhan,

In the Bengali film industry, actresses like Ri and Jaya Seal Ghosh stand out for that one film—Ghosh for Hotath Neerar Jonnyo (2004) and Ri for Cosmic Sex (2015), for which she won a best actress award. “Artistes don’t think of themselves as ‘one-film wonders’ or ‘one-book authors,’” says Odissi exponent Alokananda Ray, who acted in a television series on a special request, but says that it was a one-time stint only. “Art is an inspirational output. So if an author has a story to tell and decides that he or she doesn’t have anything further to convey, he or she may not write any more. Actors can also decide to either take a break or call it quits completely if they feel it is not something that they want to pursue. Dance is my main profession. I did act in a television serial briefly but it was something that I think was a one-time thing for me.”

Many women who had a splendid start in film have chosen to marry and ‘settle down’ or are pursuing a television career. Gracy Singh, who was adored by the audience as Gauri in Lagaan and Dr Suman in Munnabhai MBBS (2003), says artistes like her are misunderstood sometimes. “From 1997 till 2006 I was continuously acting. Nothing has changed. I was part of a dance troupe. I have done 35-40 films in all languages and worked with some very reputed Punjabi directors. I am also acting in a mega TV serial and working in an international project,” says Gracy, who appears to be at pains to shrug off the ‘one-film’ tag.

Experts say it is best if they adapt to the changes and consider good roles, like TV show Santoshi Maa for Gracy. It seems that this phenomenon was more prominent in the 1980s and 1990s and not so much in the past few years, save for examples such as Neil Nitin Mukesh and Chitrangada Singh. There is a reason for that too. “Nowadays talent agencies are handling stars, from A-listers to juniors. They work to keep them alive. Earlier, there were no casting agents and a lot of different secretaries managed stars,” says Nahta. “Then there is the social media. Web series and advertisements can keep you in the spotlight till the next good role comes your way.”

However, not everyone is malleable or can be. At times, nothing conspires to that perfect film ever again. “We were surrounded by insurmountable problems during the making of JBDY. But the film was made with a lot of innocence. I never got on to that wicket again,” says Shah. And the loss, as much as theirs, is ours too.

By Prachi Pinglay-Plumber with inputs from Minu Ittyipe in Kochi and Dola Mitra in Calcutta