The green room is a constructive place. And in a folk festival like the Jodhpur RIFF (Rajasthan International Folk Festival), it packs a curio angle too—all the folks’ instruments have to pass through these gates to get to the main stage. It’s also the most well-informed space the press card dangling from your neck can give access. Just hang around and observe all these artistes walking in and out with their gear, often meeting each other…jamming impromptu.

Sanaf, who plays the ‘tar’—a six-string Iranian instrument—as part of Tehran-based artiste Makan Ashgvari’s trio, finds a corner to tune her instrument. She’s soon approached by kamaicha maestro Dharra Khan, who politely enquires, “You’re from Iran. What is this instrument? Do you know of the kamancheh?” The ensuing conversion ends up in a minor scale jam: the percussive, individual string plucks of the tar and the sonorous glissando of the kamaicha wound by steady dholak thumps. An etymological curiosity becomes the starting point to tie two far-away cultures in melodious ways. Kamancheh literally means ‘little bow’ in Persian. And it’s spread in various forms across central Asia.

Kayamb player Tiloun Depatater

Judging from the line-up of the 11th edition of the five-day Jodhpur RIFF held this October—its schedule peppered with collaborations between local and international artists—someday, the kamaicha of Rajasthan may meet the Iranian kamancheh (one of them is the derivative of the other, one strongly suspects) in one of these folk festival green room jams—or, indeed, on stage—much before ethnomusicologists map the connections. In that sense, the proliferation of roots music festivals across the world in the past few decades makes way for imagining a global folk musician community of sorts, a space where INStruments peculiar to the mainstream eye criss-cross. Jodhpur RIFF, which is held in the majestic Mehrangarh fort of Rajasthan’s ‘Blue City’, has partnered with a few international festivals, including the Edinburgh International Festival, Woodford Folk Festival, Australia, and Cervantino International Festival in Mexico.

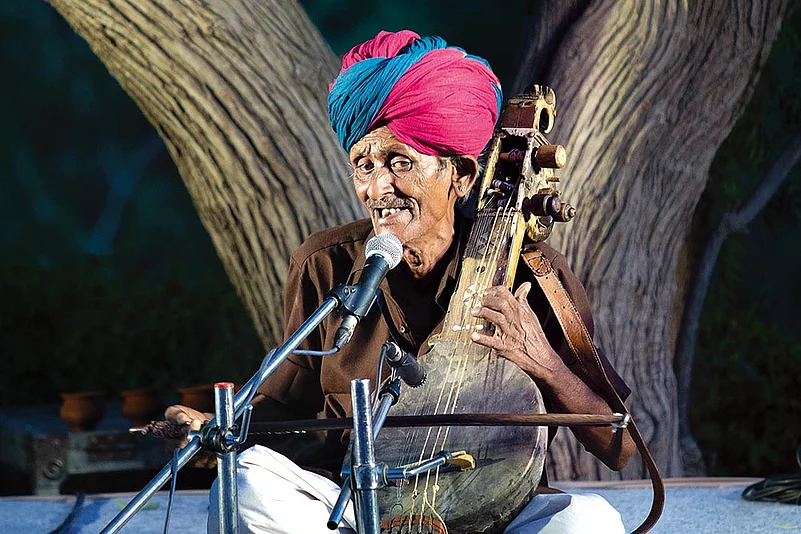

In one of the collaboration events of the fest, Dharra Khan jammed with an instrument from another part of the world to roaring applause—Grammy-winning South African musician Wouter Kellerman’s flute. Dharra’s schedule for the festival was tight—a day before the collaboration with Wouter, he had played late into the night (till almost 2 am) as part of a special performance for the festival. And he’s not the only kamaicha player at the festival. Apart from his elder brother Ghewar Khan’s performance, a kamaicha ustad by the name of Dapu Khan played to an intimate gathering in Mehrangarh on one of the evenings under the “living legends” category of the festival.

The prominence of the kamaicha at the festival bodes well for the instrument. It’s the Manganiar community’s own instrument. Made out of mango wood, with three strings prepared from goat intestine, the other 14 (or less) resonant strings made out of metal and a goat hide used to cover the belly, the kamaicha is complex to craft, hence difficult to procure. It’s also the toughest to master among the Manganiar instrument set, which includes the dholak, khartaal, sarangi, and increasingly, the harmonium.

Iranian tar player Sanaf jams with a khartaal master on stage

“It’ll disappear eventually,” says Dapu Khan in an after-show chat without much consternation, matter of fact. “Kids today go and study, they feel a bit embarrassed taking it up.” For the Manganiar community of Rajasthan and Sindh, music has been a caste-occupation. “You’ll not find it outside Jaisalmer and Barmer...maybe some in Pakistan.” Umarkot district in Pakistan, which has some Manganiar people, is the other place for the last remaining kamaichas. The place finds mention in ‘Moomal’, a folk song about a girl from Jaisalmer, who pines for her lover in Amarkot (the older name for Umarkot). The song is an essential part of Dapu Khan’s traditional repertoire.

Dharra Khan too acknowledges the challenges his instrument faces, but he has reasons to be optimistic. Dharra mentions that a few years ago, the Mehrangarh trust and Jodhpur RIFF’s organisers, along with the Manganiar community’s support, started camps in his village in Jaisalmer district where children could train under the current experts. “It’s a seven-day camp held after every six-eight months. We call out those kids who want to learn the kamaicha, since it’s the most difficult to pick up,” he says. And the signs of a revival can already be gauged. “Only two kids had come for the first camp. The number went up to four...then five. By the last camp, we had twenty students,” says Dharra Khan. He has also been sourcing unused kamaichas from Manganiar homes in neighbouring villages. I got one from a village in Jalore district, one from Barmer...I have four-five kamaichas in my house now.”

On another day of the festival, the green room resounds with a different set of indigenous instruments, this time from Réunion Island, an ‘overseas department of France’ in the Indian Ocean. When frontman Tiloun Depatater and his crew take the beats to the stage, the audience is unaware that they are headed for a party. Tiloun plays the kayamb, a rectangular instrument made out of sugarcane reeds, which is filled with canna, or other, seeds. Played by shaking it through the wrist to produce rustling triplets, the kayamb lays the foundation for the rest of the percussion to join in. Their music is called the Maloya, a music that has been as much political as traditional in Réunion. “It was banned till the 1980s by the government,” says Tiloun “As Maloya was a part of political meetings.” In the 19th century, when plantation workers were first brought to Réunion—indentured labour from India included—the Maloya eventually became a secret way to communicate among the workers.

On the night Tiloun’s beats entranced the audience, Australian drummer Gene Peterson took charge of the stage as the “rustler”, a Jodhpur RIFF conductor of sorts. It was a jam session—almost as if the green room had been shifted to the stage, a welcome intervention as far as the criss-crossing of instruments is concerned. Sharing the stage with him were Manganiar musicians, all percussionists, who had been accompanying Dharra Khan’s kamaicha all through the festival. Sanaf joined them on her tar for a number. Tom Thum, the phenomenal Australian beatboxer was also part of this global folk jugalbandi. The old got interpreted through the new and vice-versa.

By Martand Badoni in Jodhpur