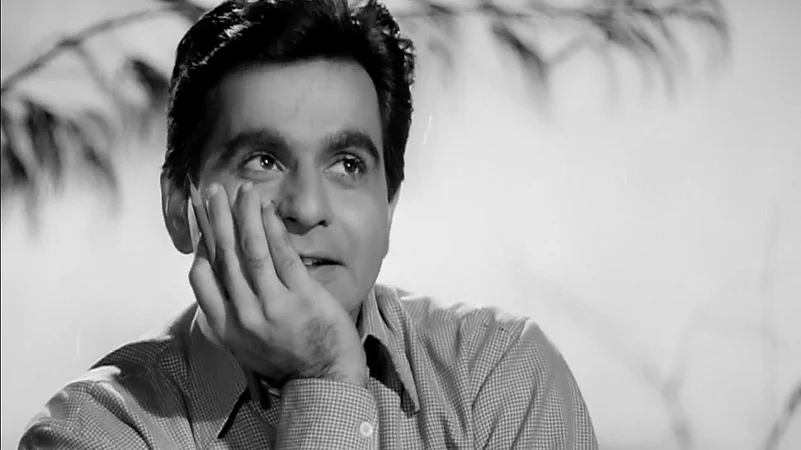

The early years of Dilip Kumar, born Muhammad Yusuf Khan, are marked by a remarkably sensitive take on masculinity—one that is charming, feels deeply, exhibits love and vulnerability, tires of failures, is afraid and isn’t afraid to accept it. He cries in loneliness, is broken in his sorrows, and his anguish permeates through the screen to reach audiences in a way that never has since. Soft expressive eyes, an even softer gaze, a voice laced with emotion, depth and fragility, Dilip Kumar’s masculinity was fearlessly sensitive, bravely restrained. Details in his portrayals, subtle facial movements, control over body language, languid yet statuesque appearances have cemented Dilip Kumar as an actor of specifics, sensitivity and softness. With a voice that was mostly measured and controlled—especially in his early work, before the tropes of toxic masculinity cast him in roles of the proverbial patriarch—and dialogue that used the beautiful elasticity of language to convey more than just meaning, Kumar shaped the contours of the hero for commercial Hindi cinema, that was as human as human can be. He was not the larger than life hero who fought innumerable number of goons to emerge victorious single handedly; neither was he the tall, well-built man, who refused to fall in pain when hit—tropes that would later come to define the ‘hero’ in Hindi films. Kumar was the man who held his own in the face of blatant wrongs and loved with a full heart.

These traits are visible across some of Kumar’s most powerful performances, which in turn are Hindi cinema’s most crucial milestones. The 1950s were a time of celebrations of idealism. While Raj Kapoor’s hero was the struggling commoner fighting class disparities in post independent India, Dilip Kumar’s hero was also an idealist, looking for ways to ensure equity and the ‘right’ thing to do across his worlds. Whether it was the lawyer in Mehboob Khan’s Andaz (1949) as the unrequited lover who takes a step back for his love to live a happy life with the man she loves, or Mehboob Khan’s Amar (1954), whose conscience post raping a woman kept calling out to his sense of justice (the moral compass however still being his love interest- Anju- played by Madhubala). In both these films, Kumar is definitely the more privileged version of the idealist than Raj Kapoor’s socialist struggler, and Dev Anand’s swashbuckling blend of a hero-anti hero. He does the ‘right’ thing—by himself and the society, both in personal and political. In Amiya Chakravarty’s Daag (1952), we see his tryst with alcohol, and his willingness to give it up in the face of hope and responsibilities towards a life that he wishes to lead. In each of these films, Kumar’s protagonists have been dramatic, but have felt a range of emotions—from guilt, to despising self, to turmoil, to anger, to resistance, to sacrifice, to love, to hurt and so many more. Each layer has been peeled and exposed to the viewer, since each has been bravely felt. This was a reality slowly eclipsed from Hindi cinema, when feeling men symbolised weakness, as the ideas of an invincible masculinity that doesn’t flinch became mainstream.

Kumar’s collaboration with Bimal Roy unlocked sensitivity to much greater levels. The expression of innocent and pure love across the beautiful hills in Madhumati (1958); the anguish that follows at her being attacked and death; the sheer desperation to avenge her one way or the other and finally finding a way to do so; or the cut backs to present day versions of the protagonists where the story first begins—each sentiment, each layer of Kumar’s portrayal as Anand and Devendra is laced in emotion that is visible for all to see. His shock at discovering the familiarity of the deserted mansion he has stumbled into, recognising his own brushstrokes in a painting he hasn’t seen before, the genuine disbelief at uncovering his own past, is told with beautiful, breathtaking honesty in his performance. “Dil tadap tadap ke keh raha hai aa bhi jaa” from the film only has Anand walking through hills, and you can’t help but rejoice in the romance of the space, and in the idea of the discovery of love.

No piece on Dilip Kumar is complete without the mention of two films, which have come to define the epitome of pain, sacrifice and unrequited love for generations, as well as the performance of pathos on celluloid. Formidable milestones of Hindi cinema, synonymous with the name of Kumar, are Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955) and K. Asif’s magnum opus Mughal-e-Azam (1960). The man who forsakes his love for the sake of societal conformity and the one who fights against it for love, are as opposite as characters can be—but are united by the sensitive, romantic and understated acting by Kumar. While Hindi cinema had been born from the dramatic and overdone portraits of theatre, Kumar’s restraint was both natural and nuanced. In Devdas, his measured and deep melancholy, his ability to portray two distinct kinds of love for Paro and Chadramukhi—one that devours him, and one that enables him to live—are what text books of method acting are made of. Furrows on his forehead, a face deeply drowned in sorrow, with Kamal Bose’s camera unrelentingly capturing the anger and angst behind the sadness are testimony to the range of emotions he was capable of. The genius of Bimal Roy and his own sensitivity allow the viewer never to judge Devdas. By the end of the film, the audience is able to view him with kindness, despite his innumerable flaws, and being a victim of circumstances of his own creation.

On the other hand is the eternal Mughal-e-Azam (1960)—the film synonymous with rebellious love, with popular culture creating a new mythical love story on the same lines as great epics like Heer-Ranjha and Romeo-Juliet. Here Salim is the headstrong prince, who believes that love needs complete commitment, and is willing to die for it. He expects the woman he loves to exhibit the same bravery for love as he does. Barring the sequence where Salim slaps Anarkali (Madhubala) in his frustration and heartbreak, when he’s made to believe that she has chosen her freedom and life over love and the resultant punishment that would come with it, every single scene is laced with love, affection and sensitivity. Salim understands Anarkali’s fears, he promises her marriage and not just love—with the promise of that marriage comes acceptance across the class divide, societal legitimacy and recognition. The feather scene is one of the most romantic and seductive scenes in Hindi cinema. Salim’s profession of love, silences perforating the film, interlocking gazes, his ability to both sacrifice and fight indicate the depth of his desire. Alongside, his understanding of the futility of war persists. At the beginning of the film, we are treated to Salim’s beating heart that continues to write poetry even from the battlefield. In the course of the film, he arranges for Anarkali to be freed and chooses not to fight. The film is an ode to love—the willingness to embrace all odds, even a violent death. The scene where he pleads with his mother, the queen Jodhaa bai (Durga Khote) saying, “Aap mujhe apne keemti hindustan mein se ek zarra na dein, lekin Anarkal mujhe bheekh mein de dein,” has his heartbreak and vulnerability etched across his face.

Then there is the other defining film of Kumar’s early repertoire, B. R Chopra’s Naya Daur (1957). The plight of the tongawalas in the face of modernisation throws into sharp relief the cost real people bear for ideas of ‘reform’. The film—that came four years after Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen (1953)—was critical, both from the perspective of performance and narrative. Kumar broke away from an urban portrayal of protagonists and embedded himself into a village, living through struggles of livelihood, love and confidence. Films like Naya Daur and Do Bigha Zameen are also crucial because they highlight the human cost of ‘development’, presenting a potent critique through narratives of class disparities and genuine struggles—a feat that seems close to impossible today, with such protagonists invisible in Hindi cinema.

Kumar’s command over Urdu and English, his knowledge of poetry, his recitations are legend. His ideas about the role of art in political thought have been a part of discourse for a long time. He refused to return the award conferred to him by Pakistan in 1999. Referring to the statement by the Shiv Sena leader that if he doesn’t choose to return it, he should leave the country and live there, he called it an “abominable pronouncement by a responsible person, which had no legal validity.” “One feels wronged. It hurts one's dignity…,” he had reportedly stated. What is crucial to note is that there was time in India when a star of his stature could fearlessly speak his mind on the politics of the day and be respected for it—an affordance that the biggest stars no longer have in contemporary times. They are called “anti-national”, their families are targeted and they are eventually forced to bow before the regime. In such a climate, how does the artist retain their sensitivity and their politics? How do they articulate their roles in society? And what then is the role of civil society in protecting the artist’s freedom of speech?

For more Dilip Kumars to exist, we must introspect on our roles as audiences and active society members.