Managing the faultlines of migration in an India on the move is a challenge that hasn’t been receiving the attention it should. When things reach a flashpoint, there is some chatter, but it soon fades into indifference. Sadly, this unresponsiveness hasn’t changed over the decades—as in the 1960s, when Bal Thackeray led a hate campaign against south Indian migrants in Mumbai; or in the 1970s, when Assamese youth erupted against the Bengali influx in a rebellion that took on contours of unforeseen complexity and whose ripples haven’t yet died out completely; or in recent years, when Thackeray’s nephew Raj launched another hate campaign in Mumbai, this time against north Indians. Perhaps the cause of this indifference is that the faultlines of migration to the big cities usually affect an underclass our elite are not much concerned with. But, it must be noted, these faultlines are exploited by politicians who ultimately, albeit indirectly, serve the regional and national elite—groups that will probably not countenance even the suggestion that they might be benefiting from such discord.

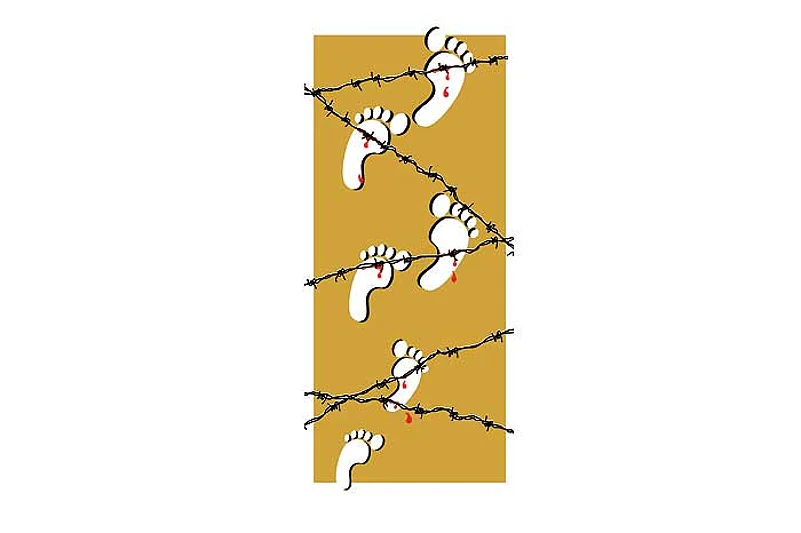

Tension usually builds up slowly over several years. Consider the dynamics in a midsize city like Jaipur. From an hour after sunrise to noon, groups of casual, semi-skilled and unskilled workers wait for small contractors and middlemen to pick them up for the day’s odd job or two. These job-seekers are from the hinterland districts of Rajasthan. Earlier, they would work on infrastructure projects in the city or in their own districts, jobs that assured them a few months of employment. But now, the firms that take up such projects prefer to bring in low-paid labourers from Bihar, keep them at the sites only for the duration of a project, then move them to another project elsewhere. Migrants from the districts of Rajasthan see them as job-snatchers. The resentment this breeds is readily transferred to migrants from other states who, unlike the rapid-deployment labour brought in by big companies, have become part of the city, performing jobs intrastate migrants are unable or unwilling to take up, for they tend to go off to their villages more frequently. All three groups—the short-term brigades brought by big firms, the intrastate migrants, and those from other states—live in deprivation. Competition for jobs and space escalates the risk of crime, conflict, conflagration.

Land sharks, labour contractors, businesses that need labourers in large numbers, politicians—they all feed the middle-class anxiety such a situation creates to make the migrants even more vulnerable. For instance, in Jaipur and Ajmer, a perverse reduction is being deployed: all migrants are Bengali speakers, all Bengali speakers are in fact illegal Bangladeshi Muslims, all crime and terrorist activity is their work. Whipping up communal frenzy in this way makes it easy both to deliver up slum clusters as real estate to builders and constituencies to politicians of a certain hue. Similar processes—not confined to Jaipur or Ajmer, and which other political parties are certainly not above using—create volatile situations exploited to the hilt by the predators who create them.

There is also another kind of faultline, created when powerful migrants arrive to prey upon weaker locals. The tribals of Jharkhand have long resented the Diku, or the outsider, first British, then Bengali, and later Marwari or Bihari, who exploited them. The tribals of Dantewada and Bastar too have similar terms to express their resentment for migrant communities that have long exploited them. Reduced to a minority in their own land, Jharkhand tribals first sought a separate state; now they are entwined in the Maoist insurgency. In Dantewada, many tribals are fighting a near civil war against the State, again under Maoist leadership.

Other not so visible faultlines are also forming in subaltern India. For instance, female foeticide and a falling sex ratio have created such a situation in Haryana and parts of Rajasthan that women from far-off Jharkhand, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and even Sikkim are being trafficked to the alien macho-rural milieu of these states. Scholars need to look at these and other faultlines too, study their dynamics, and map the resentments they create before it is too late. There’s no telling how they might ultimately erupt.