All night they kept arriving, by the tens of thousands, clambering down from the roofs of buses, spilling out of trains. They streamed into Taregna, a tiny railway “halt” that isn’t quite a station—nothing but a nameboard and two benches serving as a landmark for local passengers, who walk across the open track to reach the village at the tail-end of a small town, Masauri. By the time Bihar’s chief minister Nitish Kumar arrived around 4.30 am from Patna, driving on a road built specially for the occasion, and now lined with police and CRPF troops, the public enclosure was already packed, and latecomers had to settle down where they could—along the railway tracks, on electricity poles, on rooftops, some even on top of Masauri’s telephone tower, patiently awaiting a celestial spectacle that tradition had taught them to shun as evil.

6:16 AM Taregna: Waiting, expectant crowds minutes before the eclipse

6:27 AM Taregna: The area plunges in darkness during the total eclipse

No one had heard of Taregna until a few months ago, when a team of astronomers searching for likely places to view this century’s most spectacular solar eclipse zeroed in on the village of some 200 to 300 cramped homes of brick and mud. It fell right on the “line of totality” (the few places on earth from where one could see the moon’s shadow totally covering the sun for an unusually long three-and-a-half minutes). The astronomers also discovered that the village, according to local legend, was the site of the ancient Indian astronomer Aryabhatta’s observatory, from where it got its name, Taregna (Counting Stars). The team, all members of a voluntary organisation dedicated to popularising the study of stars, SPACE (Science Popularisation Association Of Communicators and Educators), decided it was the ideal place to bust the average Indian’s myths and fears about eclipses. But even they did not quite anticipate what this potent mix of recovery of lost heritage and modern carnival would soon trigger.

Ask Amitav Ghosh, head of Patna’s planetarium. When he was first alerted about SPACE’s plans for a public viewing of the solar eclipse both in Patna and Taregna, Ghosh placed an order with a private company in Delhi for 1,000 solar glasses—the polymer film-coated plates which filter out the sun’s harmful rays. It was a reasonable order, going by the demand during previous eclipses. But, to his surprise, they were sold out within days. His next order was more ambitious: 3,000. That too was snapped up, and Ghosh placed yet another order for 3,000. But on Monday, two days before the eclipse, Ghosh found himself in a fix: the queues at the counter outside his office were getting longer and more vociferous, and customers were coming to him with recommendation letters for buying the glasses. He called his supplier to courier him whatever stocks they had. They sent him only 5,000 more. Ghosh wisely shifted the sales out of the planetarium, near the main gate, where for the first time in its history, a mile-long queue wound its desperate way to the counter. Other voluntary organisations, like the Bombay-based Navnirmiti, also ran out of filter glasses, despite making 1,00,000 pairs.

Another nation-wide science organisation, Gyan Vigyan Samiti, which brought 500 astro-enthusiasts from across the country to view the eclipse from Patna, was similarly taken aback by the enthusiastic response to the Suryagrahan Utsav they organised in Patna’s Gandhi Maidan. With a shortage of solar goggles, they devised an ingenious solution: they ordered one-metre strips of polymer film sheets which they mounted on wooden frames, so that 10-20 people could view the eclipse simultaneously.

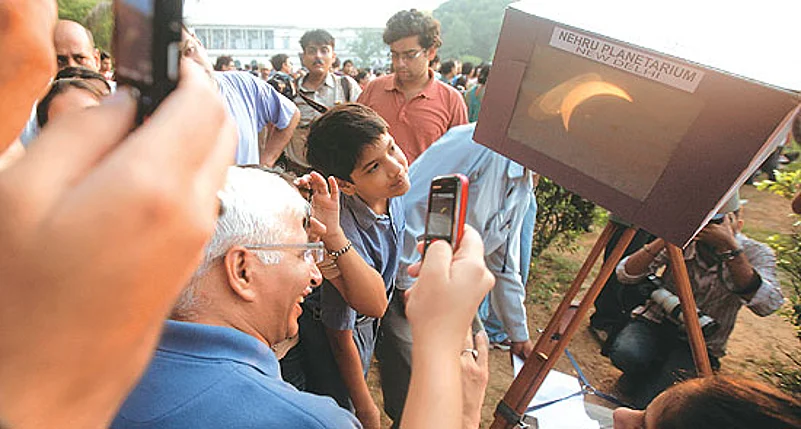

At Nehru Planetarium, Delhi, during the eclipse

Even the city’s opticians say that during the run-up to the eclipse they got several customers a day demanding solar glasses. “We had to direct them all to the planetarium,” says Ramchandra Prakash, proprietor of the city’s leading Crown Spectacles shop, who belongs to the old school which believes in the malevolent effects of an eclipse on health and fortune. But with the eclipse being such a hot topic of discussion among his family and friends, he could not resist going up on his terrace with his family to watch it. But before that, he took the precaution of consulting his guru, who prescribed the recital of 108 mantras before the eclipse and a special puja afterwards to counter its ill-effects. And in response to the demands of his other devotees, his guru had to finally inscribe on a blackboard outside his ashram the mantras and pujas to be offered as expiation by those who succumbed to the reigning temptation.

Scientists, of course, count this sudden willingness on the part of astrologers to bend their rules to accommodate popular sentiment as a victory over the enemy they’ve been fighting for decades. For instance, during the total eclipse in 1981, as SPACE organiser Sachin Bahmba recounts, “It was almost as if there was a curfew in the country, thanks to the fears instilled by astrologers. Doordarshan scheduled three feature films for the day because people refused to stir out of their homes.” In 1995, things were beginning to change a bit—scattered bands of enthusiasts were willing to overcome their fears and go out to view the eclipse. But it was the astrologers who had a field day even then, spreading fear and superstition through the many TV channels that had sprung up by then.

During this eclipse, however, scientists encountered little or no public resistance. Science educators like D. Raghunandan of the Delhi Science Forum, here for Patna’s Suryagrahan Utsav 2009, attribute it to the scientific temperament that has been inculcated over several solar eclipses. The real breakthrough came during the last total eclipse in 1995, according to him, when scientists made a determined effort to motivate ordinary people to go out and see the celestial phenomenon for themselves. But what scientists are perhaps missing is the new profile of eclipse-chasers that have emerged out of the 7/22 event. People like Pavan Kumar, who had travelled 120 km from Lakhisarai to Patna to put in his application for further studies at the Indira Gandhi Open University. Straying into the tent where the Suryagrahan Utsav was taking place in Patna’s public grounds, Pavan was pleased to discover that anyone was welcome to come and watch the much-talked-about solar eclipse, that too under the guidance of India’s best astronomers. So he decided to return the next morning from Lakhisarai with several of his friends for the public eclipse viewing. “That generation which was suspicious of eclipses is now dead,” he explains. At Taregna, schoolgirls like Rina Kumar, a ninth standard student, persuaded their parents to let them attend the utsav by arguing that it is part of their education.

But it’s more than the aspirations of thousands of youngsters eager to be part of the Shining India dream that resulted in record crowds of eclipse viewers in Bihar—1,50,000 at Taregna alone, while thousands more turned up in stadiums in neighbouring districts as well as Patna. It’s also Bihar’s sense of ownership of the century’s most-touted celestial spectacle. As Nitesh Singh, a student at one of the many private colleges that are mushrooming in the state, explained, “It’s a moment of great pride for us Biharis battling the image of backwardness. The world has discovered the village where Aryabhatta lived, and we are discovering our own heritage of great scientists.”

In the end, the fickle clouds robbed the crowds of the celestial show they had turned up to see, but nothing could dampen their pride and enthusiasm. They listened avidly to the scientists’ explanations and when the earth turned totally dark for a few minutes, a loud cheer went up. Leela Kumari, who had taken a bus to Taregna with her husband the previous evening, insists it was well worth the trouble: “It was an unforgettable experience. So what if we didn’t watch the eclipse occur? At least I saw stars in the day, something that I hear won’t happen for another 114 years.” Standing next to her is Asha Kumari, a housewife who walked in the dark with her five children, including an infant in arms, to see what was going on in Taregna. Show or no show, Asha is now convinced that the eclipse has been a good thing. “Otherwise, do you think so many people, including world-famous scientists, would come here?” This was good news for scientists and volunteers of SPACE, who had been fervently hoping that this eclipse would not be a repeat of 1999—a total eclipse that turned out to be a total washout, thanks to the monsoons. “Once people are willing to come out and see things for themselves, it’s bound to affect the nation’s scientific temper,” points out Raghunandan. But for Bihar, it was more: a hope, perhaps, of a second sunrise like the one they’d just witnessed.