My debut work of fiction, Patna Blues, is mostly set in Bihar’s villages and mofussil towns. I wanted to give my novel a distinct flavour by incorporating socio-cultural elements unique to these places. One day, walking down memory lane, I rediscovered the treasure trove of folklores my brothers and I had grown up with. Those fantastical tales were mostly about jinnats (djinns), pandooas (river ghosts) and rakas (demons with a thousand eyes), and had been in circulation for centuries. They were an integral part of our collective imagination. Given the way our elders narrated the stories, we believed those supernatural beings existed in reality.

As a kid, whenever I walked through the streets of my village alone, I felt the lurking invisible presence of some paranormal creature.

We had a family myth about the guardian djinn, a friendly spirit who had been protecting our family for the past 300-400 years. We called that imaginary djinn ‘Jinnat Dada’ (Grandpa Djinn). I have been told Jinnat Dada, like the big brother in George Orwell’s 1984, kept watch on us, and that, if we did anything morally wrong, he would punish us.

Interestingly, there were some stories that were used for treating different kinds of ailments. Since my village didn’t have easy access to a qualified doctor or a proper hospital, we were totally at the mercy of quacks, faith healers, witch doctors and practitioners of alternative medicine. Some of the healers just told you stories in order to restore your health, nothing else—no bitter pills, no painful injections. When I was 10 or 11, I had gone through such a treatment. My memories of that day are still fresh. I even used that amusing experience with slight changes in my novel in which the protagonist Arif Khan goes through similar treatment for his illness.

In the early 1980s, I had fallen sick with fever and chills. I trembled and shivered continuously. My mom consulted the local quacks and homeopaths, but their medicines didn’t offer any respite. Worried, she talked to my uncle and got him to take me to the doctor in the nearest town, which was five to six hours away by a bullock cart.

Meanwhile, one of my grandaunts told my mom that I was possessed by Jarwa-Jaraiya, hence normal medicines wouldn’t work. “You must call someone who knows the rituals to get rid of Jarwa-Jaraiya. Inshallah! Abdullah will be fine by tomorrow,” my grandaunt insisted. A few other relatives agreed with her.

A few hours later, a frail-looking woman with silver-white hair, arrived at our house. Looking at me, she confirmed it was Jarwa-Jaraiya indeed. She asked me to come out in the courtyard and sit on a mat on the floor because Jarwa-Jaraiya needed an open space to fly away. Then she got ready to start the ritual, which began with the telling of a story, the story of Jarwa and Jaraiya.

Once upon a time, a beautiful widow lived in a village with her only son. Her son was very mischievous. One day he broke something precious and, in anger, the widow hit him on the head with a wooden ladle. He started bleeding. Enraged by his mother’s behaviour, the boy left home for the city, where he was adopted by a rich, childless couple. Twelve years passed.

After the death of his adoptive parents, the boy inherited all their property and business. One day he was passing through the village alone on business. He thought the place looked familiar and decided to stay in the village for a few days. The same evening he saw his mother, but did not recognise her. Memories fade in 12 years. He fell in love with her. In those 12 years, the boy had become an elegant and dapper young man. So, the widow too failed to recognise him. When he proposed to her, she instantly said yes. Finally, they got married. Soon after her marriage, the widow became pregnant.

One morning, while massaging her husband’s head, she saw a deep gash. When she asked him, he told her that when he was a child, his mother had hit him with a stick and he had run away from his village when he was perhaps six or seven years old. He could not recall the name of his village or his mother’s face. But the woman looked at his face and understood why this man’s face resembled that of her first husband so much.

When they came to know that they were mother and son, they were so ashamed and sad that they decided to commit suicide. They prepared a pyre and jumped into it. Even in death, their souls did not find peace. The man became Jarwa and the woman became Jaraiya. Now they trouble people by possessing them, making them shiver. Whenever the story of their shameful liaison is repeated in the presence of the person they possess, they run away.

“O Jarwa and Jaraiya, if you have shame, go away from here. If you don’t go away, I will repeat the story of your sinful liaison again,” the old lady spoke in a very loud voice, looking directly into my eyes as soon as she finished the story.

I had listened to the story with great attention and, in fact, enjoyed this unusual treatment. The very next day my fever was gone and I stopped shivering. And, within three days, I was perfectly alright.

For many years, I believed that the story had cured me. However, now I think it was a kind of placebo effect, coupled with the homeopathic medicines I was taking, that might have done the trick. And, a few months back, when I talked to my daughters—one of them is 11—about that incident, they laughed and wondered how I could believe that listening to a story would be a cure for any kind of ailment.

In response, I could only smile.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Story Can Cure You")

ALSO READ

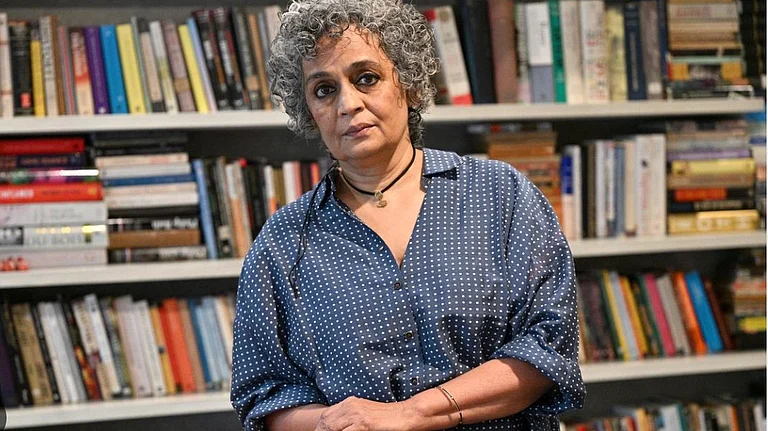

Abdullah Khan mumbai-based novelist, screenwriter, literary critic and banker