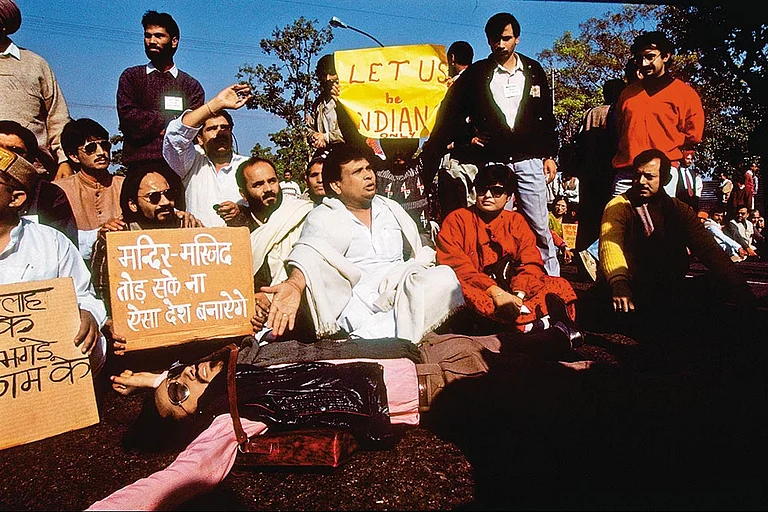

During the partition of India, one of the most heated discussions was around the nature of the state that our country would adopt. Ultimately, after a series of discussions and debates, it was decided that the state would not have any official religion and would follow secular tenets. This was an inspiring decision as swinging towards majoritarianism is quite easy, and even enticing at times, than taking the right stance.

In Secularism: How India Reshaped the Idea, political philosopher Nalini Rajan goes deep into its philosophy while also covering its gradual evolution in Indian polity. Published by Speaking Tiger, this is their latest addition to their Ideas of the Indian Constitution series.

The book is divided into four main segments. In the first chapter—Understanding Secularism—the author initiates the conversation by defining secularism as ‘the belief that the state, morals, education, etc. should be independent of religion’, but goes on to disagree with the limited understanding around it and presents a much more contextual and multifaceted meaning.

She traces the first mention of equal treatment to all religions in the Indian subcontinent to the Proclamation of Queen Victoria issued in 1858 just after the revolt of 1857. But as India moved forward to form its own constitution, it was already established that separate electorates for Muslims would not be possible. But simultaneously, the Constituent Assembly realised that just the promise of equal opportunity won’t be enough to correct the historical wrongs that several castes have suffered through. Hence, it worked on several provisions like the application of corrective measures, including reservations in education, services and legislature.

The conclusion of the Constituent Assembly Debates (CAD) guaranteed people the right to propagate and practice their religion but also cemented its secular structure.

In the following two chapters—Debating Secularism and Judging Secularism–Rajan goes on to deconstruct the layered aspects of secularism while keeping the historical aspects in the background. The CAD also shows how critical and sensitive the issue of secularism was for a country that had recently suffered a partition based on religious identities.

But an interesting statement made at the CAD by Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib Bahadur on majoritarianism caught my eye where he stated, ‘Can you think of any parliamentary democracy where there is no Opposition? Unless there is Opposition … the danger of its turning into a fascist body is there’—a comment which still stands true and something with which we are still struggling as a democracy.

In the concluding chapter—Deepening Secularism—the author poses several important questions about the state of minorities in India and whether we have progressed or regressed when it comes to safeguarding their rights. The 2006 Sachar Committee Report burst the bubble of the mythical Muslim appeasement politics proving that there has been minimal materialistic development of the largest minority group in the nation and goes on to state the data about their dismal representation in government services.

In a country like ours, which has a fractured communal past attached to its freedom from colonialists, it becomes important to analyse the materialistic conditions of all communities and take appropriate steps to aid in their holistic development. Today, as we see a rabid form of majoritarianism engulfing our mainstream politics and discourse, it poses an important question about whether we did enough to actually instill a feeling of secularism that is contextual to the demands of our country into the minds of Indian citizens. This book helps the reader to understand the journey that secularism in India has gone through and make sense of its deficiencies. It also enables the reader to pose pertinent questions regarding the same and demand for necessary changes.

(Chittajit Mitra is a writer-translator and co-founder of RAQS)