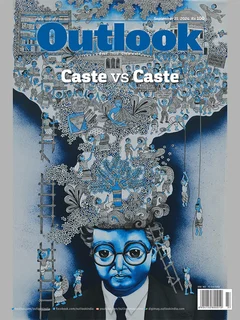

PasThis is the cover story for Outlook's 21 September 2024 magazine issue 'Caste vs Caste'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

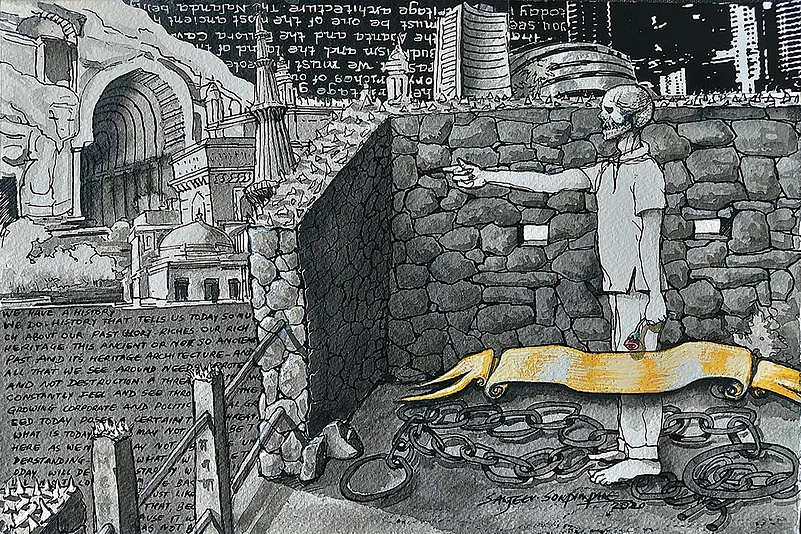

The political processes in India, particularly since Independence, have uncannily pushed Indian Muslims to the margins. The push, quite evident since the 1990s, is largely the result of three interrelated conceited-imageries in Indian politics. One, the burden of partition is ominously placed onto the Muslims, even to those who stayed back in India, either by choice or necessity, and inferably were stereotyped as traitors, anti-national and untrustworthy. Since partition days, India as an ‘imagined community’, or perhaps as a ‘spectacle democracy’, reproduces its collective ethical identity, where we find, at times, the corrosion of secularism, and, at times, the near-complete exclusion of Muslims. The past, of course, has been undeniably rocked by communalism, violence and persecution of Muslims. Two, Islamophobia emerged as the dominant mode of prejudice against Muslims, leading to widespread exclusion, hate crimes and disparagements. The Hindutva project, tracing its roots to the iterations of Veer Savarkar that Muslims are enemies of the Indian nation, has fuelled an even more extreme demonisation of Muslims and has exacerbated the climate of fear and violence feeding into the rising Islamophobia. And third, the neo-liberal project, with its in-built proclivities to exclude vulnerable groups from the market distribution of resources, and more precisely from the labour market, has taken a toll on Muslims.

Indian Muslims, going by the Sachar Committee Report, are defined by those having low income, high illiteracy, widespread poverty, irregular source of income, poor health records and quite a low morale. To understand Muslim marginalisation, it is also imperative to explore their class-compositions intermeshing with their caste-categories, so to say, to locate the circle within circles. Muslims in India are possibly imagined as a monolithic religious minority, but empirically they are quite a diversified and heterogeneous community, notably more in the anthropological/sociological sense. They are differentiated along ethnic and socio-cultural lines into various groups and sub-groups and also in caste and tribe groups. Their stratified social order is akin to any other religious community in India and that makes them a bit unique when compared to their counterparts in Islamic countries and elsewhere. Their diversity, and the large-scale subalternity, drives us to make an effort to know them from below.

Although the Muslims in India share a few basic Islamic precepts, and in times of extreme communal crisis, act as a single religious community, they are in normal conditions both horizontally and vertically divided vis-à-vis their socially constitutive categories. Even during the ascendency of Islam, the Arab society was organised on the basis of the ‘notion of honour and status’, ‘birth and unity of blood’, ‘tribal aristocracy’, with traders and chieftains having wide control over diacritical symbols. The desert society was more horizontally stratified than vertically, because in the early phase, marked by the expanse of the Islamic empire, the groups did not have much material difference and so less elaborate class stratification. With the expansion of Islamic empire beyond Arab territory, the Arabs started calling non-Arabs ‘ajamis’, or dumb, and even called Indian Muslims ‘mawalis’, or subservient, resulting further into the elaborate system of social stratification.

In India, when Islam entered around the 8th century CE, the differentiation among Muslims was between the descendants of ‘foreign ancestors’, who were proudly called as ‘ashrafs’, and the local converts, predominantly Dalits and untouchables, who were contemptuously referred to as ‘Ajlafs’. Ashrafs got further sub-categorised, the basis being their ethnicity, domicile, class status, civic and religious leadership and aristocracy, and were named as Sayyed, Shaikh, Mughal and Pathan. The former two are believed to have descended from Arab ancestors and the latter two from Mughal (Mongol) and Afghan conquerors. The Ajlafs—the coarse rabble—are the toiling masses and peasants, with no noble ancestry but with innumerable occupational groups. The social gradations among Ajlafs are marked by the past caste characteristics having close resemblance with the Hindu varna and jati systems. At the bottom of the Muslim’s class-caste compositions are the ‘arzals’ or ‘raizals’, basically engaged mostly in scavenging, sweeping and other menial jobs. E A Gait in Census of India, 1901 (Bengal Report), said that the distinction between Ashrafs and non-Ashrafs correspond to the ‘dwijas’ and ‘shudras’ of the Hindu caste-system, and in E A H Blunt’s book, The Caste System in Northern India (1969), we find castes among Muslims in some detail.

Pasmanda, which literally means ‘those who remain(ed) left-out’, is the group that combines largely the Ajlafs and Arzals and has gained currency in its usage as a religious-neutral term. The Pasmanda movement, mainly led by former Rajya Sabha MP Ali Anwar, says that Pasmanda is a term, not necessarily applicable to any specific religion, that locates its ideological moorings in the anti-caste (Ambedkarite) and social-justice (Lohiaite-Mandalite) politics and treats the RSS-BJP as a Brahmanical-Manuvadi communal formation. Like Pasmanda-Dalits, Pasmanda-Muslims are looking for equality, dignity and rights. In recent decades, particularly since the late 1990s, Pasmandas as marginalised Muslim groups have been organising and articulating for their empowerment and self-development.

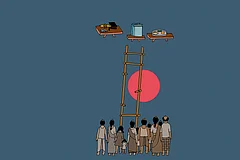

When it comes to affirmative action and reservation policies for Muslims, particularly Pasmanda Muslims, the Indian state hasn’t evinced much interest, despite the fact that the Indian Muslim groups are relatively more deprived in terms of education, income, employment and poverty than the Dalits and Adivasis. The Sachar Committee report shattered the whole myth of so-called ‘Muslim appeasement’. Muslims have relatively poor access to physical assets, including landholdings, and remain at the lower end of the labour market hierarchy. They have a low political and institutional representation—there is not a single Muslim in the incumbent council of ministers—and suffer from widespread discrimination leading to their overall socio-economic backwardness. The moot questions, in such a milieu, are (a) whether the State’s affirmative actions, including reservation in jobs and educational institutions, need to be addressed to the Pasmandas only or to the whole community, and (b) should Pasmandas be further sub-categorised with a chunk of them given Schedule Caste (SC) status?

The Ranganath Misra Commission Report (2007), set up to look into various issues related to linguistic and religious minorities, recommended (a) 10 per cent reservation of seats for Muslims be given in non-minority educational institutions, and 10 per cent in government jobs, (b) SC status be given to Dalits in all religions—which, in effect, meant Muslims and Christians, as Sikhs, Hindus, and Buddhists already have their Dalits in the SC status, and (c) sub-quota of 8.4 per cent for religious minorities in the 27 per cent Other Backward Class (OBC) quota, with an internal break-up of six per cent for the Muslims. The post-Sachar Evaluation Committee (2014), headed by Amitabh Kundu, also recommended affirmative action for Muslims, including reservation quotas, to offset the near absence of their cultural capital related to educational access and entitlements mainly in northern India.

Since the establishment of the Minorities Commission in 1978, there have been numerous committees set up to look into the political and socio-economic questions of Muslim marginality. The Sachar Committee undoubtedly brought into the public discourse the central issues of Muslim’s deprivation, discrimination, representation and exclusion. However, the question of affirmative action in the form of a series of policy measures and reservation, and the modalities of categorisation and sub-categorisation remains to be seen on the ground. It is important to note that reservation, as argued by Prabhat Patnaik, achieves the goals of both efficiency even in the short run and distributive justice.

And, reservation for Pasmandas, which is religion-neutral, can be defended on the grounds of the same principles and articles of the Constitution that defend reservation for the SCs, STs, and OBCs, or even Dalits among Sikhs and Buddhists. The fact that Pasmandas are underrepresented in almost all socio-economic and political institutions and are continuously discriminated against and targeted, basically by the stereotypes (re)produced by Islamophobia at large, requires their active political participation. They must participate in the progressive and secular movements that have the potential to address the oppressive and exploitative policies of the neo-conservative governments, backed by neo-liberal power elites, and also have the potential to counter the ultra-nationalists’ urge for unapologetic violence and communalism. As for the incumbent government, it must take the Ranganath Misra Commission report seriously and implement it, provided that the K G Balakrishnan Commission—looking into the possibility of giving SC status to Dalit converts to Islam and Christianity—comes out with some better and more radical reforms.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Tanvir Aeijaz teaches public policy and politics at the University Of Delhi and is honorary vice-chairman at centre for multilevel federalism (CMF), New Delhi

(This appeared in the print as 'Circle Within Circles')