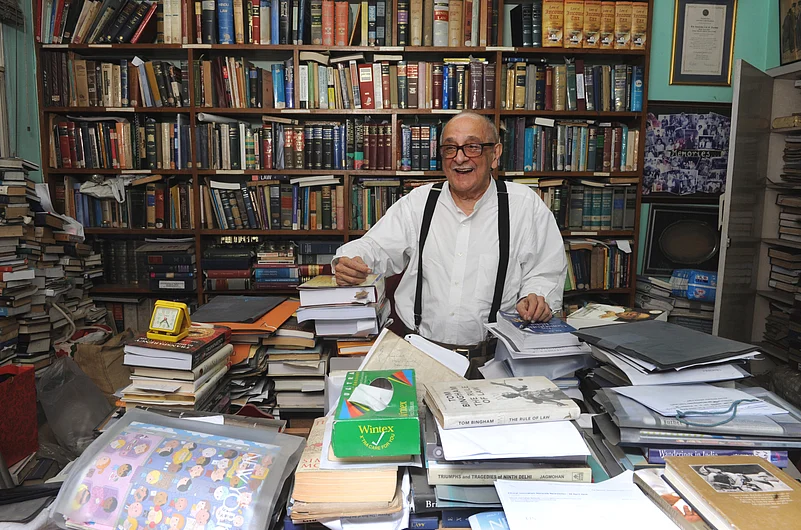

Fali Sam Nariman, one of the most eminent jurists and senior advocates of India, has passed away at the age of 95. A doyen of India’s legal history, his place in the annals of law in India remains uncontested with a luminous career dotted with landmark cases and lifelong contributions to constitutional law.

Born in 1929, Nariman graduated from the Government Law College in Bombay in 1950. He started his legal practice in 1949 at the Bombay High Court and was appointed as a Senior Advocate in the Supreme Court of India in 1971. He served as the Additional Solicitor General of India from 1972 to 1975, following which he resigned upon the declaration of Emergency by the Indira Gandhi government in 1975. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1991 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2007.

Besides serving as President-appointee member of the Rajya Sabha between 1999 and 2005, from Nariman had also served as the President of the Bar Association of India; Vice-Chairman of the Internal Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce; as an honorary member of the International Commission of Jurists from and a member of the London Court of International Arbitration. He was also appointed to the Advisory Board of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, and served as Chairman of the Executive Committee of the International Commission of Jurists from 1995 to 1997. Throughout his life, he had advocated for the rights of people on the fronts of equality and secularism, and championed for the protection of Constitutional values.

In his autobiography ‘When Memory Fades’, Nariman has talked about his desire to “die in a secular India” having lived and flourished in a secular India as well. He has been critical of verdicts like the Supreme Court’s stand on the abrogation of Article 370. In an interview with The Wire last year, he talked about the situation in India today being “like a veiled Emergency, but with the added prevailing mood of anti-Muslim, anti-minority sentiment”.

Following the news of Nariman’s death, the country’s legal community came together to pay homage to the person and his contributions to constitutional law and advocating for its basic structure. “A great son of India passes away. Not just one of the greatest lawyers of our country but one of the finest human beings who stood like a colossus above all . The corridors of the court will never be the same without him,” said Senior Advocate and politician Kapil Sibal.

Here we list some of the landmark cases that Nariman was part of.

I.C. Golak Nath v. State of Punjab

In this 1967 case, Nariman argued for the petitioners that Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution under Article 368 did not include articles contained in Part III of the Constitution which dealt with fundamental rights.

The Supreme Court bench, by a thin majority, agreed with the petitioner’s submissions, pointing out that Article 13 (2) states that Parliament cannot make a law which infringes on fundamental rights as mentioned in the Constitution. Justice Subba Rao, the then CJI, used the doctrine of prospective overruling for the first time to preserve the constitutional validity of the Constitution (Seventeenth Amendment) Act, the legality of which had been challenged. It was held that a constitutional amendment, also being an ordinary law within the meaning of Article 13, could not be in violation of the fundamental rights chapter contained in the Constitution and all such amendments thus far were deemed void.

The Collegium system of appointing judges

Nariman’s contribution to the Indian judiciary is majorly embodied in the three cases that established and upheld the Collegium system of appointing judges. These are the Second Judges case, 1993; the Third Judges case, 1998; and the challenge to the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) in 2014.

1993: In The Second Judges Case, the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA) v. Union of India, Nariman represented the SCAORA to challenge the decision a five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court took in 1981 where it gave the central government the final say in matters regarding judicial appointments and transfers, where the President could refuse recommendations made by the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and there need not be concurrence. Nariman argued that the consultation with CJI must be seen as binding. If not, it infringes on the independence of the judiciary, as the judges would provide a more competent understanding on the appointment of judges, argued Nariman. In 1993, the nine-judge bench agreed with Nariman’s arguments and the Supreme Court Collegium was established, which is tasked with making binding recommendations for the appointment of judges to the apex court and High Courts, and is in place till date.

1998: Nariman made submissions to assist the court in answering a reference made by then President KR Narayan, regarding clarification on the procedure for appointment of judges following the second judges case. The court, answering the reference in 1998, clarified that the CJI must consult other judges of the Supreme Court before making any recommendations for judicial appointments. The size of the Supreme Court Collegium was also expanded to five senior-most judges from three.

2015: The National Judicial Appointment Commission Act, 2014, amended the Constitution to add Article 124A which created a commission for judicial appointments comprising the CJI, two other senior SC Judges, the Union Minister of Law and Justice, and two “eminent persons'' who would be nominated by a committee comprising the CJI, Prime Minister and Leader of Opposition. Nariman, for the SCAORA, argued that the commission would muscle in on the independence of the judiciary with central government and the legislature playing a part in the selection and appointment of judges. In 2015, the NJAC was struck down, reinstating the collegium system for judge appointments.

TMA Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka

In this 2002 case, Nariman argued for the right of private educational institutions to establish and manage their establishments, a right safeguarded by Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution, ensuring the freedom to practice any profession or occupation.

The Supreme Court in addition to affirming that the state has the right to frame regulations applying to minority-run educational institutions, and the status of religious or linguistic minorities and religious and linguistic minorities, who have been put on a par in Article 30, will have to be considered on a state-wise basis. The court also held that the government’s regulations cannot “destroy the minority character of the institution or make the right to establish and administer a mere illusion”.

Union Carbide Corporation vs Union of India

Nariman represented Union Carbide in the case against the Union of India where a fatal chemical leak from the company’s plant had led to the major calamity in Bhopal in 1984, killing over 3000 people instantly and around 15,000 people subsequently, according to various estimates. The hearing of the case began in 1988 in which Nariman helped the company make a deal with the Government of India that gave victims $470 million as compensation. However, in his autobiography, he reflected on navigating the moral layers that the case brought with it and expressed his regret about taking it up.