As the Dalai Lama marks his 90th birthday, the question in everyone’s mind, from China’s Xi Jinping, to India’s Narendra Modi, and America’s Donald Trump, down to his faithful followers, is the same. Who will take over his mantle as the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists?

While speculation about his likely successor has been doing the rounds for decades, the question is now gaining urgency as age is catching up with the Tibetan leader. A spiritual icon and a global celebrity in his own right, the Dalai Lama is also a master strategist and has skilfully navigated his way through exile, repression of his people in Tibet, the power of Communist China, but managed to keep his flock together and the Tibetan question alive.

Now, with Beijing eager to install a pliant successor of its own choosing, the Dalai Lama is quietly but deliberately working to ensure that China’s plans to control Tibetan Buddhism’s future are thwarted. This is a spiritual leader who remains a formidable political force.

Along the way, he has faced criticism from restless young Tibetans challenging his non-violent middle-path, his decision to remain within China but with cultural and religious rights intact instead of independence, and a few missteps that has stirred controversy.

Simple Monk

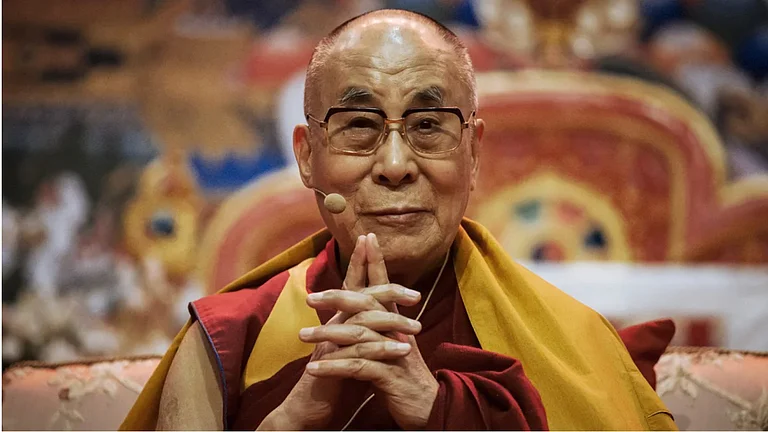

"I am a simple monk", is how the Dalai Lama describes himself. Dressed always in the maroon robes of his sect and sometimes sporting a Rolex watch on his wrist, the Dalai Lama is one of the most recognisable faces in the world. His message of peace and non-violence has resounded across frontiers and won him the Nobel Peace prize in 1989. He has an enviable fan following among the rich and famous.

Hollywood actor Richard Gere has been a devotee for at least two decades and more. So is Eva Longoria, Lady Gaga, Sharon Stone, Selena Gomez and a host of other A-listers. He has met with presidents and prime ministers and charmed them as much as he has his hordes of supporters, not just among devout Tibetan Buddhists but ordinary people all over the world.

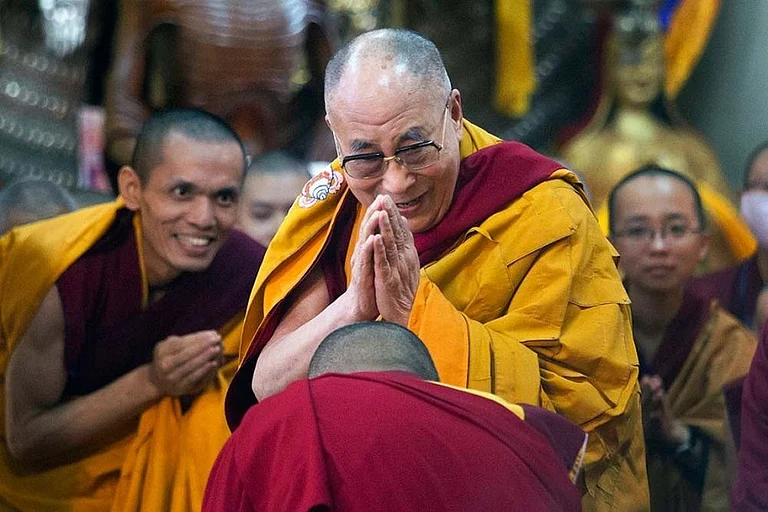

“There is something about him that hits you when you are in contact with him. I remember my first meeting with him in Paris, when I was at the airport to receive him. I was tongue-tied and overwhelmed in his presence", says Amitabh Mathur, a senior Indian bureaucrat and an adviser to the Home Ministry on Tibetan Affairs, recalling his first meeting with the Tibetan leader. He was there to greet him as the Dalai Lama was on his way to Oslo to receive the Nobel. “There is a kind of energy and compassion that flows from him and touches all those around him,” he adds.

Everyone who has interacted with the Tibetan leader speaks of his playful nature, his instinct to pull a beard whenever he sees one. This could be a throwback from his childhood, where he recalls pulling at his father’s moustache: “I remember pulling at his moustache once and being hit hard for my trouble.” He loves making faces at children who are delighted. But his love for kids has also landed him in a major controversy in 2023, when a video surfaced of him kissing a young boy on the lip and then asking him “can you suck my tongue.” That naturally led to a huge backlash. His office later apologised, and a Tibetan cultural commentator, who said it was a likely mistranslation of a phrase and is often a playful gesture between elders and children in Tibetan culture.

Reincarnation

The Dalai Lama has kept the world guessing on his succession. He had once said in 2011 that the institution could end with him. Again, he had jokingly said that a woman and a “blonde woman” could succeed him.

In his latest book, Voice for the Voiceless, he was more forthright, writing that his successor would be born in the ‘free world’, obviously outside China. But now he has made his views more explicit. He has said in a recorded message at a religious ceremony in Dharamshala on June 30, that the next Dalai Lama would be found and recognized according to tradition laid out and that the search would be entrusted to the Gaden Phodrang Trust, that he founded in 2015 and manned by trusted senior monks that he had chosen to oversee religious and spiritual matters. So, the reincarnation and choice would be with those he trusts. He laid to rest earlier apprehension that the 600-year-old tradition of reincarnation of the Dalai Lama would end with him. He was explicit that the Dalai Lama’s office has the sole authority to recognise the reincarnation. "No one else has any such authority to interfere in this matter", he emphasised, making it clear China cannot choose his successor.

China’s foreign ministry quickly rejected the Dalai Lama’s claims: "The reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, the Panchen Lama and other great Buddhist figures must be chosen by drawing lots from a golden urn, and approved by the central government", said foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning at a regular press briefing, referring to a selection method introduced by a Qing dynasty emperor in the 18th century.

Geo-Politics of Succession

In most cases, the succession of a religious leader rarely causes a ripple beyond the faithful. But the impending succession of the Dalai Lama is almost a geopolitical flashpoint, drawing in three major powers: China, India, and the United States. For Beijing, the stakes are high — control over the next Dalai Lama is part of its broader strategy to tighten its grip over Tibet and legitimise its rule. The Chinese foreign office's reaction has made it clear it will appoint its own reincarnation, a pliant figure who toes the Communist Party line and weakens the Tibetan resistance.

India, home to the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile since 1959, finds itself in a delicate position. It will likely hedge its bets, providing quiet support to the Tibetan cause while avoiding a direct confrontation with China. India and China are just about getting back to repairing ties after the 2020 confrontation in Ladakh.

Kiren Rijiju, parliamentary affairs minister and an MP from Arunachal, quickly asserted after China’s statement that only the Dalai Lama’s office will decide on the successor. Many within India's strategic circles believe the time has come to play the "Tibet card' a symbolic reminder to China that New Delhi, too, can stir the pot in Tibet, considering China’s ironclad support for Pakistan on Kashmir. The MEA’s response, unlike Rijiju’s, is guarded. “The government of India does not take any position or speak on matters concerning beliefs and practices of faith and religion. Government has always upheld freedom of religion for all in India and will continue to do so,” MEA spokesman Randhir Jaiswal said on July 4.

US-CIA

The United States, has little ambiguity in its stance. It has consistently supported the Dalai Lama and the right of Tibetans to choose their spiritual leader without interference. Backing the Dalai Lama’s wishes allows Washington to challenge China’s expanding influence and open yet another front in its broader effort to contain Beijing’s rise. The CIA was involved in Tibet from the late 1950s to 1970. The Americans saw this as an opportunity to thwart the spread of Communism. By this time, the ideological warfare between Capitalism and Communism had begun. The US actively helped in training, arming, and funding the Tibetan resistance, besides extending diplomatic support to the Tibetan freedom movement. The CIA contacted the Dalai Lama’s brother Gyalo Thondup, who organised a group of Tibetans to travel to Colorado for arms training. The trained group was parachuted back to Tibet but was quickly caught and executed by the Chinese authorities. The CIA called off operations after Nixon and Kissinger broke the ice with a visit to China and a meeting with Chairman Mao Zedong.

But America’s honeymoon with China is now over. Successive US administrations, including that of President Donald Trump, regard China’s growing political and economic clout as a challenge to its power. So, Washington will certainly finger China if it tries to impose an official candidate as the next Dalai Lama. So, the choice of the next Tibetan spiritual leader is not just a matter of faith, but one of global power play.

Early Life

On a cold winter’s day in 1935, a search party sent out by the Tibetan government to identify the new Dalai Lama landed at a modest home of a farmer’s family in the village of Takster, in north eastern Tibet. The death of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1933 led several parties to fan across the country searching for the baby believed to be the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama.

The party zeroed in on Lhamo Thondup, a two-year-old born into a farming family who was able to identify some of the possessions of the previous Dalai Lama. He was taken away from the family and brought up and educated by senior lamas. In the winter of 1940, Lhamo Thondup was taken to the Potala Palace, where he was officially installed as the spiritual leader of Tibet.

In 1950, the Chinese Communist Party, which had established itself in Beijing, turned its attention to Tibet. The CPC claimed Tibet was a part of China. A seventeen-point agreement was signed between the Chinese and the Tibetan local governments and ratified in October 1951. The Tibetans later said that they were made to sign the agreement under duress. The Chinese initially let Tibet remain much as it was, but gradually began to uproot what it dubbed as the “feudal serfdom” that was in place in Tibet and promoted by the lamas of the Potala Palace.

The People’s Liberation Army began cracking down on supporters of the Dalai Lama to 'free' Tibetans from serfdom. The crackdown led to a series of armed revolts in eastern Tibet areas of Kham and Amdo in 1956, that was put down with an iron fist.

On the 10th of March 1959, after nearly a decade of repression by the soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army, Tibetans gathered in protest and surrounded the Potala Palace in Lhasa, fearing that China would arrest the Dalai Lama. The failure of the uprising forced the Dalai Lama to flee to India through Nepal. In India, he was welcomed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He and his followers were settled in Dharamshala, where the Dalai Lama set up a government in exile. The Tibetan leader has been an exile ever since. In 2011, he handed over power to a democratically elected prime minister and retired from temporal affairs.