Has the aam aadmi slipped from the radar of the Congress-led UPA government? Presenting his first full budget in Parliament, finance minister Pranab Mukherjee strove continuously to emphasise that the aam aadmi was the primary focus of the government’s biggest accounting exercise. In fact, he called it a vision for high but inclusive growth that would improve the common man’s lot.

But who, after all, is this proverbial aam aadmi? Is he the average middle-class taxpayer, who is relieved that the tax slabs have been rejigged for the next financial year to help the family hold on to a little more money, thereby mitigating the impact of high inflation on the household budget? Or does he represent the hundreds of millions who are struggling to eke out a living in the villages or urban slums? Isn’t he the marginal farmer trying to produce enough on his small piece of land to meet the family needs and get out of debt?

Actually, there seems to be some confusion here. Perhaps that’s got something to do with the hosannas the finance minister has been hearing during interactions with industry bigwigs about his ‘delicately’ balanced budget. There are few to point out that the real aam aadmi has not been identified, much less provided for, in the budget. “The aam aadmi, according to this budget, is now a taxpayer, addicted to the corporate English-language news programming on television,” civil activist Biraj Patnaik comments cynically.

Running on Empty

- Agriculture: Total allocations see a dip; lower fertiliser subsidy, increased urea price; special regional needs overlooked; poor focus on irrigation

- Food management: Lower allocation for food subsidy; drop in public sector investment

- Inflation: No plan to dampen high food inflation—higher fuel prices may add to price pressures

- Rural development: Less than 6 per cent increase in allocation for special programmes for rural areas, where good civic infrastructure largely remains a dream

- Health: Funds don't match needs to upgrade facilities and tackle malnutrition; maternal and child health get less attention

- Employment: Inadequate provision to meet multiple challenges—like skill development, upgrading ITIs

- Social security: Encouraging start, particularly in health insurance for migrant labour; and now a social security net for unorganised workers

- Education: Funds to improve facilities inadequate to bridge the existing gap

- Energy: Sharp 51 per cent reduction in allocation

Growth In Social Sector Spending

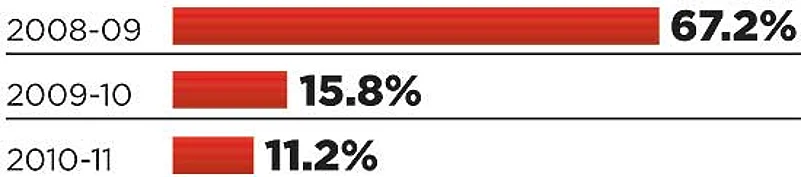

Spending on social sector schemes compared to the year-ago budget

No doubt, life is tough even for a middle-class family in these inflationary times, but it does not compare with the hardship faced by those living on the street or slums, doing odd jobs or living off begging. It’s not, it must be stressed again, an insignificant number: more than half of the country’s population lives in poverty. The 2010-11 budget has little or no provision to ensure them a life of dignity.

On the face of it, a 37 per cent allocation of the plan budget for social services—including education, employment, social security, water and sanitation, among others—speaks well of the government’s intentions. But probe a little deeper and you find there is a nearly 13 per cent drop in allocation for social security and welfare. Again, there’s just a 6 per cent rise in allocation for meeting nutrition needs at a time when India has one of the worst malnutrition levels. Shockingly, there’s also a drop in provision for food subsidy and no provision for implementing the Right to Food legislation, currently awaiting Parliament approval.

| “We have received more complaints of ‘starvation’ deaths in the past one year than in the last three years put together. It’s ominous.” Biraj Patnaik, Advisor, Food Security |

| “There is no connection between what the government says it will do and what it does. That strategy has not changed.” Ashok V. Desai, Economist |

| “I wonder why there is not enough political anger at the very high inflation, as used to be seen in earlier days.” Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Centre for Policy Research | ||||

| “Irrigation, agriculture’s most important input, finds no special mention, though Bharat Nirman would have provisions for it.” M.S. Swaminathan, Agriculture scientist |

| “I am disappointed that while Pranab talks of the budget being a vision document, it doesn’t talk of things concerning the poor.” N.C. Saxena, Former advisor to the PM |

| “Had the FM got into pure aam aadmi mode and tweaked social sector expense vastly, it would’ve been a disaster for business.” Mukesh Butani, Tax head, BMR Associates | ||||

| “In the last 20 years, most money for employment generation has gone to the formal sector but created less than 1% more jobs.” Ashish Kothari, Kalpavriksh |

| “The reduction of subsidies without steps to improve the supply chain would be a short-lived solution. It will have price effects.” Shashanka Bhide, Economist, NCAER |

| “At the raw end are the Dalits and the Scheduled Tribes...the gap can be bridged if the funds are innovatively designed.” Paul Diwakar, Dalit activist |

Unlike in 2007-08, when it stepped up its social sector allocation by a steep 67 per cent to operationalise the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) across the country, there’s a marginal increase of Rs 1,000 crore in its allocation this fiscal. Though there is a rise in allocation for health and education, it is not enough to meet the demand. Particularly disappointing is the lack of focus on children, who constitute 41 per cent of India’s population. Take, for instance, the right to education—the commitment to implement it is belied by a marginal increase in share for literacy and school education from 2.7 per cent to 2.81 per cent of budget allocation.

The problem, we are told, is managing the fiscal deficit—government expenditures have to be curtailed to manageable levels by cutting down on ‘populist’ measures. This belt-tightening marks a shift in tack for the Congress-led government, which got re-elected in 2009 on the plank of its concerns for the poor and the under-privileged. Given that food inflation is at a high 17 per cent—this, of course, hurts the poor the most—and that growth is not yet fully on the rebound, the budget gives treats to only a small, prosperous part of the electorate. Is that the complete India story?

How do you reduce food subsidy in a country where millions go hungry?

“I simply don’t know whether this budget is giving a nudge towards job creation...I wonder why there is not enough political anger at the very high inflation, as used to be seen in earlier days,” says Pratap Bhanu Mehta, head of the Centre for Policy Research. Worse, the budget not only cuts allocations to the poor, but also doesn’t seem to have a clear vision to solve the many problems in delivery of resources. Many of the real issues have been glossed over in this budget, feels Ashish Kothari of Pune-based NGO Kalpavriksh. For him, the talismanic aam aadmi is really the “over 70 per cent of the population who are out of the tax net as they are either below the poverty line or only slightly better off”.

For instance, though the National Development Council had made clear rules in 2004 directing all ministries to make plan allocations for the marginalised communities in development schemes, only half-hearted measures are seen. “Though development has taken place, at the very raw end are the Dalits and Scheduled Tribes. There is massive denial of these allocations,” says Paul Diwakar, general secretary of the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights. There has been an 80 per cent jump in allocation this year for the ministry of social justice and empowerment—unlike other ministries, where there is no such focus.

Unfortunately, with no fixing of clear responsibility on the utilisation of funds, they often get diverted. Two major flaws with the budget, economist Ashok V. Desai states, is that it does not encourage growth-promotion activities nor does it seek to provide succour to those who need public assistance, such as the poor, the old and the children in a manner that it reaches them. “The budget’s strategy has not changed—as such, it is largely irrelevant to the aam aadmi.”

Take a look at agriculture, the mainstay for more than half of India’s population. Despite the avowed intention to boost farm production and productivity to realise the target of 4 per cent annual growth, the finance minister has cut the allocation for agriculture and allied activities by almost two per cent. What is upsetting experts is that the thrust on boosting pulses and oilseeds production is to be realised with Rs 300 crore for 60,000 villages—that works out to Rs 50,000 per village. Similarly, a measly Rs 400 crore has been allocated for replicating the Green Revolution in six states.

While corporates and taxpayers have gained, concomitantly there has been a 13 per cent drop in allocation for social security and welfare.

Agriculture scientist M.S. Swaminathan, though muted in his criticism, states that while a roadmap for farm sector growth has been indicated in the budget, “the achievement of the goals of above steps will be possible within the very small amounts provided in the budget only if state governments can introduce a ‘deliver as one’ approach” for dovetailing different projects to achieve desired results. Experts feel this is going to be a tough order: in the case of oilseed and pulses, it’s not funds but lack of will by the farmer that is affecting production. But who can blame him when he gets only Rs 4-5 per kg for whole pulse? After processing, it gets sold in retail market for over Rs 50 per kg.

Despite the many deficiencies in the rural development focus, some experts are happy that the finance minister has recognised the participation of women in farm economy by proposing a Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana with an initial outlay of Rs 100 crore. Also, steps have been taken to improve social security for unorganised sector workers with plans to set up a special fund with Rs 1,000 crore. Of course, one wonders how the amount will suffice for over 450 million people working in the unorganised sector.

Though happy with the focus on welfare schemes, rural employment and social security thrust, National Council of Applied Economic Research agronomist Ajaya Sahu is critical of the fact that the “government is not specific about investments in irrigation and improving productivity. This should have been given more stress. However, only allocation of funds is not enough. How they are utilised is more important.”

This is the fate of the aam aadmi in Bihar. Civic infrastructure will remain a dream for many as the rural development budget has gone up by just 6%.

Many others share the disappointment at the government not addressing real issues. Says N.C. Saxena, former advisor to the prime minister, “Pranab Mukherjee says the budget is a vision document, but does not talk about things that concern the poor—whether land acquisition or Forest Rights Act. There seems to be a conspiracy of silence about the non-taxpayers.” Though there is continuing support for the largest rural employment scheme, NREGA, many are turning critical. With no proper assessment of the outcomes, many like Saxena and Kothari see it fast becoming a dole instead of creating assets like drought-proofing and other infrastructure.

Similarly, with very little coordination between implementing ministries, many of the programmes for the poor continue to see inadequate fund utilisation or outcomes that are below expectations. This is particularly so in the case of education and health programmes. As Mehta puts it succinctly, “If most of the programmes like NREGA, health and education, road construction work effectively, then only will the aam aadmi benefit from what the budget says.” In another crucial area—food security—the government is going slow. “Not a single rupee has been allotted for the National Food Security Act,” avers Patnaik. “This reflects an intention not to implement it in the next financial year.”

There is a disappointing lack of focus on children, who make up 41 per cent of the country.

Sadly, things haven’t changed for a long while. The situation is akin to 1980, when Indira Gandhi had stated that the benefits of the five-year plans were not reaching the people who deserved it, particularly the marginalised. It can be argued that budgets don’t, and can’t, change much. But for a self-stated vision document, it seems that the corporates’ proximity to North Block delivers the only clear rewards from this budget. That is strange coming from a government that had figured out the magic formula, and returned to power riding on the back of the aam aadmi.