- Consistently high GDP growth rates

- Positive agri-growth in six quarters

- Infrastructure yet to catch up

- Social sectors slacking in growth

- Manufacturing rising at over 10%

***

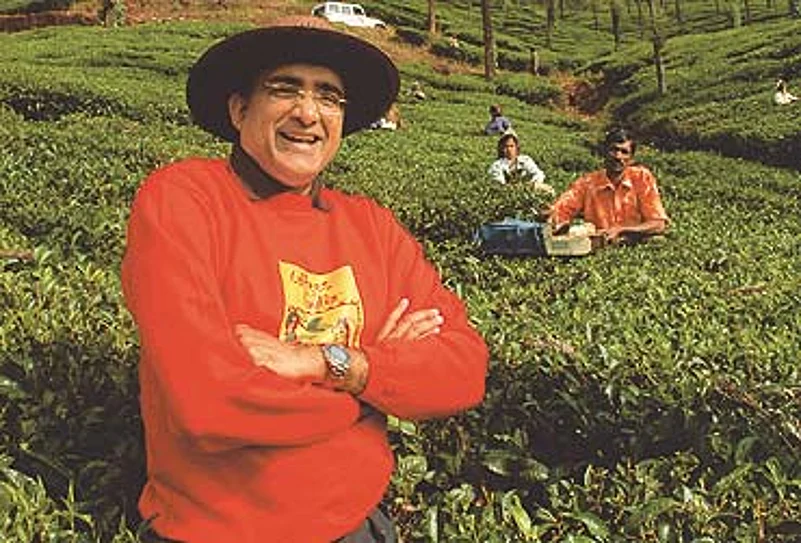

Even in the still and serene surroundings of his 2,000-acre estate on the Sahayadri slopes in Chikmagalur in the Western Ghats, Ashok Kuriyan can feel the hustle-and-bustle and the pace of the Indian economy. At Balanoor Plantations, the "feelgood" factor has gripped every worker, including its MD Kuriyan. After all, despite a huge rise in input costs, it netted a cool profit of Rs 30 lakh this season, compared to a "no-profit, no-loss situation" in the previous one. "If we had not got the Rs 25 lakh subsidy last year, we would've been in serious trouble," says Kuriyan.

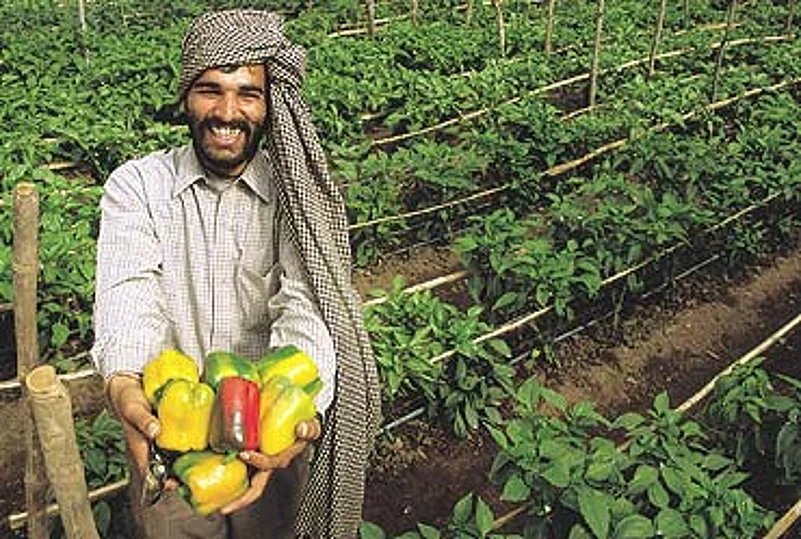

Thousands of kilometres up north, in Bilaspur, Himachal Pradesh, Jagdish Thakur has sold 2.5 lakh carnation stalks, grown on a part of his 13-acre plot, in the last seven months at the wholesale mart in New Delhi. His earnings: Rs 10 lakh. In neighbouring Punjab, Jaswinder Singh of Bhondli village in Ludhiana is making hay by selling vegetables, instead of traditional crops like wheat and rice. From the 22 acres (of the 35 he owns) devoted to vegetables, his annual income is Rs 14-15 lakh. Today, he wants his son to be an engineer, he's building a Rs 35-lakh mansion, and waiting to ink a contract farming deal with either Reliance Industries or ITC.

Pradeep Kumar, a farmer in Himachal Pradesh, shifted from the traditional maize to grow coloured capsicum. His income from just one crop this April: Rs 9 lakh.

Farmers, and agriculture, are a critical component of India's growth story. It's agriculture that has inevitably derailed it in the past. It's here that you still find farmers in far-flung rural areas who seem untouched by 15 years of economic reforms. It's in this sector that you witness an inherent contradiction that has always plagued the Indian economy—thousands of farmers earning higher profits, and similar, or more, committing suicides. And unless agriculture becomes less dependent on monsoons, India's GDP growth will invariably remain skewed.

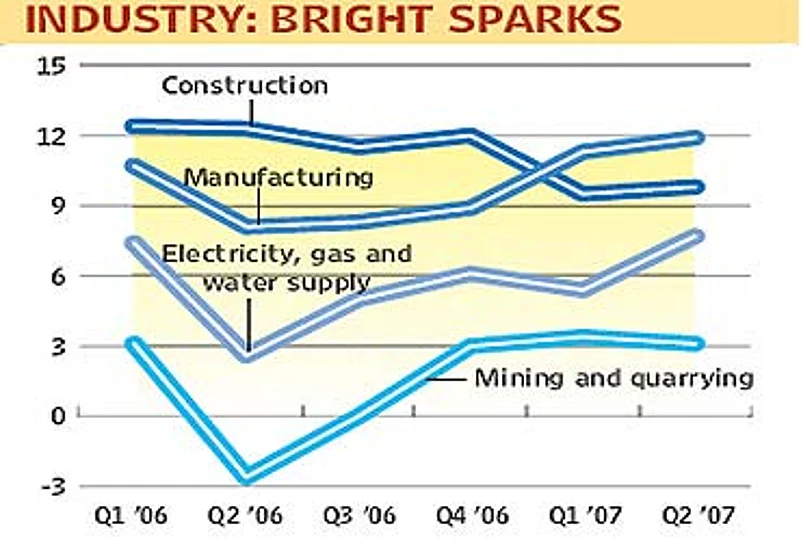

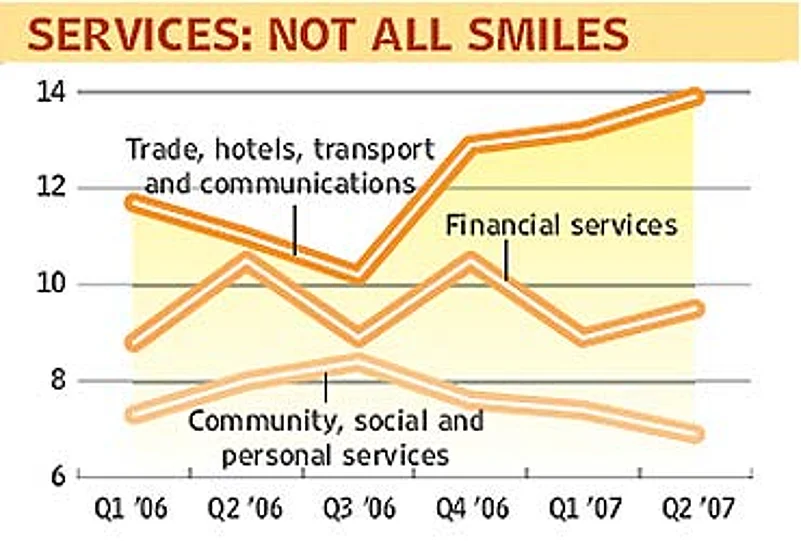

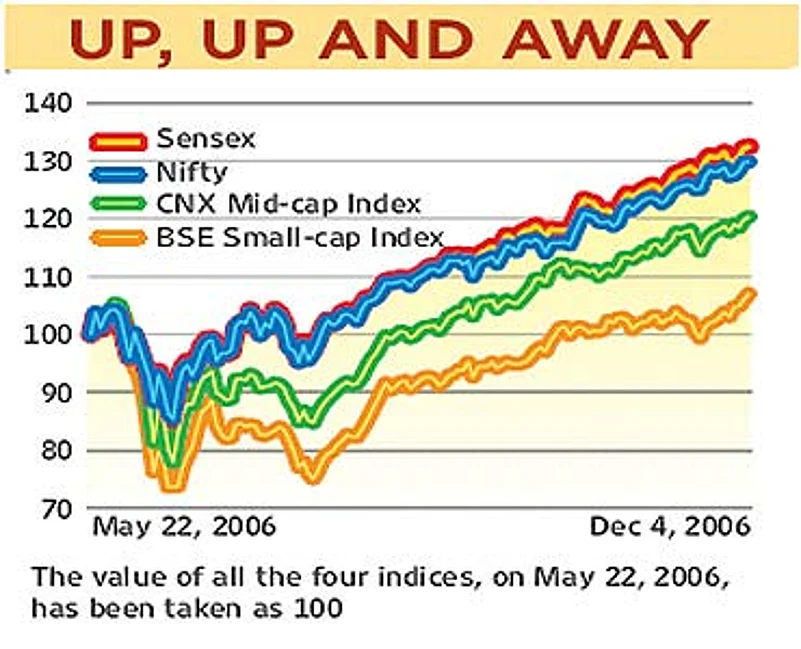

Fortunately, the rain gods have been benevolent, which has enabled agriculture to clock a positive growth in the past six quarters. Given the fact that industry and services have been galloping away at a frenetic speed, the country has witnessed unprecedented GDP growth rates—9.2 per cent in Q2, 2006-07 (see graphics). More importantly, it seems to be on the verge of doing the impossible, that is, achieving a 10 per cent-plus growth in the near future. Looks like Planning Commission's Montek Singh Ahluwalia's claim that India is likely to witness a double-digit growth during the 11th Plan period will turn out to be true.

All figures in per cent

"This is a critical inflection point in India's economic journey. All sectors are performing; very rarely have all of them fired at the same time in any country. What's happening in India is reminiscent of what happened in the US in the 1950s and 1960s, when it emerged out of World War II and started rebuilding its economy," explains Arun Jain, chairman and CEO, Polaris Software. Adds Kishore Biyani, CEO, Pantaloon Retail, "The world is moving from a knowledge economy to a creative one, which works on imagination, speed, collectiveness and seamless functioning—and India is certainly joining in."

In the midst of an all-encompassing euphoria and collective confidence in ever-enlarging sections of the Indian society, there are several crucial questions that loom large. What's driving India's GDP? Is it related to global, local, or glocal factors? Is the country, like China and Brazil, creating pockets of prosperity that's helping the classes and leaving the masses in disarray? Finally, is this unbelievable economic saga sustainable?

We start this trek by grappling with the obvious: the causes that have led to this enthralling dance of the economic elephant. At both the global and domestic levels, a demand upsurge and an almost unabated rise in prices of commodities and other products has helped. Take the case of Balanoor's Kuriyan, who has gained because international coffee prices rose 10-12 and aggressive marketing helped the plantation extract premium prices from global buyers. Local prices too have shot up; for instance, Balanoor benefited from a 20 per cent rise in India's rubber prices, thanks to booming demand from tyre companies.

Anand Mahindra’s M&M had a winner in its SUV Scorpio. The vehicle saw a 20% growth in Q2, ’06-07.

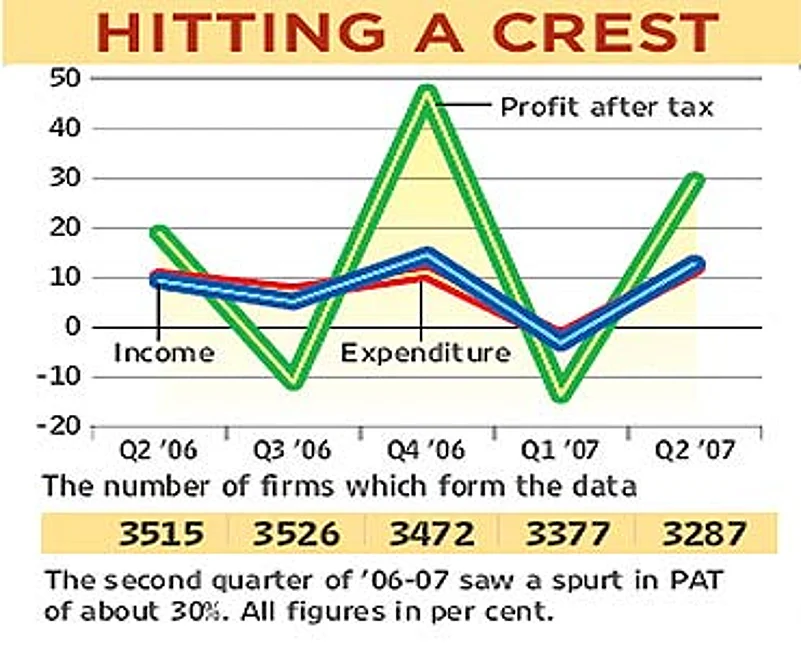

A similar combination yielded spectacular returns in manufacturing. To cite just one example, M&M's Scorpio SUV registered a 20 per cent volumes growth in Q2, 2006-07. Nothing epitomises this better than the revenues and profits of India Inc. In the past five quarters (June 2005 to September 2006), the growth in income of over 3,000 firms has been positive in four quarters. The trend for net profits is not as exciting as they were in the red in two quarters. But the impressive fact is that in two quarters—Q4, '05-06 and Q2, '06-07—net profits zoomed by over 47 per cent and just under 30 per cent, respectively.

But all good things have a negative tinge. The price rise has led to a hike in input costs, and raised apprehensions of an inflationary flare-up. Complains Kuriyan, "Diesel and petrol prices have gone up enormously. This has upped our power costs, as we depend on diesel pumpsets that cost twice that of state-supplied electricity. Wages have gone up due to an increase in variable DA. Plantations are unique as they have allied social costs on housing, medical, and schools for the families of employees. Despite this, we made profits."

The same story is reiterated by other entrepreneurs, and most companies have been able to absorb the impact on raw materials, increase prices of their final products, and still push volumes. This is clearly visible in the fmcg sector, which has been wracked by price wars between HLL and P&G in the recent past. But HLL managed to increase the price of Lux by seven per cent and Surf Excel Blue by three per cent. As Ketan Karani of Kotak Securities told Outlook last month, "Both volumes and pricing is up, and it has taken growth to another level."

All figures in per cent

India Inc's resurgence is also reflected in its capex, or investments in adding or building new capacities. A recent research showed that manufacturing and services firms spent over 1,00,000 crore; a majority of it to buy plant and equipment and the rest on capital work-in-progress and fixed assets (land and building). The figure was 29 per cent higher than the previous year, and the compounded annual growth rate has been 17.55 per cent in the past five years. Not many have seen this kind of capex in recent corporate history.

What's important is that Indian groups are eyeing high-profile overseas acquisitions and aiming to become global players. The Tata group's $8-billion bid for the UK-based Corus is an indicator; so is the fact that between January and October 2006, Indian firms doled out thrice the amount to buy foreign firms, compared to what the mncs spent to take over Indian ones. A banner headline in a British newspaper, after Corus accepted the Tata bid, captured the new Indian mindset. It read: 'The Empire Strikes Back'. Ratan Tata hinted at the newfound self-belief among Indian entrepreneurs when he called it the "defining moment" for Tata Steel.

All figures in per cent

Polaris' Jain traces the short history of this transition. In 1999, as the world panicked over being inflicted by the y2k bug, dozens of Indian software firms helped provide solutions to global firms. It marked the beginning of the outsourcing, and later offshoring, momentum that propelled Infosys, Wipro andTCS into the big league. It forced the brick-and-mortar Indian firms to think differently. "As a lot of attention was diverted to software companies, it made the old-economy ones straighten up and think of new strategies. That was the time several decisions were taken by the latter, which is holding them in good stead today," he explains.

The manufacturers acquired a sharp focus, a penchant for building brands, and clear-cut strategies. It also nudged them into looking at the globe as the market for their products, as was the case with software services. That led to a strategic evolution, and Indians started selling to the world, especially in areas like pharmaceuticals. Take the case of Dr Reddy's Lab, whose Q2, 2006-07 revenues and profits pole-vaulted by 250 per cent and over 300 per cent, respectively, and was labelled a "landmark growth" by its MD Satish Reddy.

But the bulk of its revenues, at 88 per cent, came from foreign markets, and North America accounted for over 50 per cent of the Q2 turnover. A mix of growing its core businesses, and overseas acquisitions, contributed to this phenomenal growth. Another pharma major, Ranbaxy Labs, has eight overseas plants, and earns four-fifths of its revenues from these units. Its CEO, Malvinder Singh, told Outlook recently that "there's a growing realisation that we've no option but to go global". G.V. Prasad, vice-chairman and CEO, Dr Reddy's Lab, echoed this sentiment, saying the Indian market was not enough to "sustain our growth momentum".

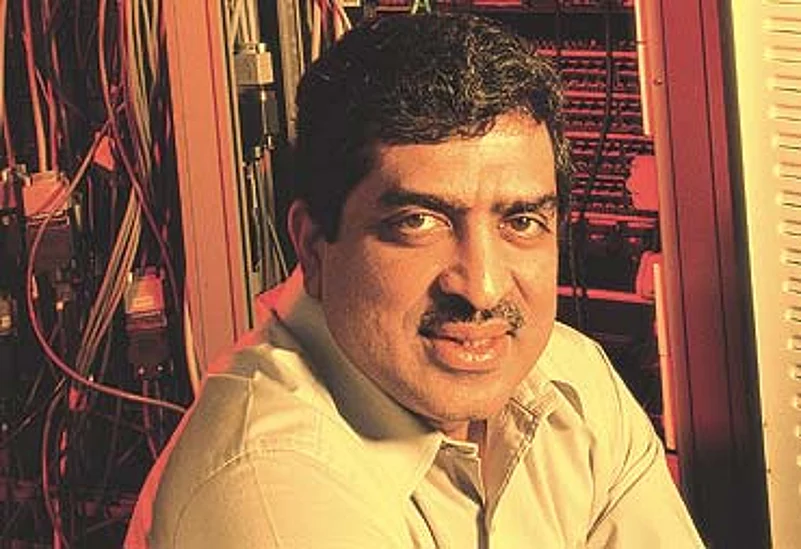

Nandan Nilekani of Infosys. Software firms like these hit the big league this century.

As Indians turned into software czars, as offshoring moved lakhs of jobs to India, as the new economy fever gripped the world (including Indians), as domestic manufacturers looked outwards, and as the India brand became global, the character of the Indian businessman too changed. Suddenly, his appetite for risk went up, he became more ambitious and adventurous, and he wasn't afraid to enter new sunrise sectors that were opening up domestically and internationally. In a nutshell, he became an entrepreneur.

Once again, we turn to agriculture to establish some of these facets. For, nothing can do it more authentically than a few examples of how farmers have begun to change. Yet again, we go back to the stories of Jagdish and Kuriyan. In 1997, when Jagdish experimented with gladioli flowers, it turned out to be a dismal failure. "I incurred a loss of Rs 20,000, was chided by my father for not focusing on traditional crops like ginger and maize. I threw the bulbs into the Sutlej, and vowed never to grow flowers again," he remembers.

But he tried again, because the market environment changed. The greenhouse technology helped increase yields. The farmers could ship their products directly to Delhi-based commission agents, without depending on local middlemen. Finally, the demand for flowers boomed in the past few years. Today, Jagdish talks like a CEO: "Just 0.01 per cent of Indians use flowers, compared to 80 per cent in the developed nations. So, the prospects for growth are huge. A Dutch company wishes to import my produce. I think I will also experiment with coloured capsicums as my neighbours are getting handsome returns from it." The family of Pradeep Kumar, another Bilaspur farmer, is making a killing by growing red and yellow capsicums, which sell at Rs 100-140 per kg in Delhi and each plant yields nearly 10 kg. His income from just one crop sowed on a small portion of his 20-25 acres (most of which is devoted to traditional crops like maize) this April: a whopping Rs 9 lakh.

Ashok Kuriyan’s Balanoor Plantations in Chikmagalur diversified and made profits.

In Kuriyan's case, external factors made him think differently. A decade ago, coffee prices crashed and, in the last 10-12 years India lost out in the tea exports market to more reliable suppliers like Sri Lanka, Kenya and Vietnam. In a jiffy, the two crops that Balanoor depended on lost huge sums. "It was then that we realised that relying on a single (or double) crop was disastrous," he says. Now, both tea and coffee gardens are interspersed with timber trees, which are embraced by pepper or vanilla creepers. The estate also grows rubber, areca and cardamom. Such a mix has benefited him this year too; the losses from tea, whose selling price is Rs 10/kg less than costs, have been more than made up by profits in others.

The same taste for diversification and risk-taking has afflicted others. Pantaloon's Biyani talks about how he realised that India was witnessing the mushrooming of a new consumption class and retail would be the next big thing. "We felt we could help people consume more. We understood that the new growth would be pushed by a new generation which, unlike ours born to socialist parents, is born to democratic ones and has a consumption mindset. In business, timing is important. Nothing can succeed ahead of its time," he says.

He was bang on target. Organised retail is the fastest-growing sector today and KSA Technopak predicts that the annual market size will treble to over $21 billion by 2010. Just the top ten players, including Reliance Industries, Pantaloon, Bharti, Spencer's Retail and Tatas, will invest $18-20 billion in the next five years, and generate annual revenues of $50-60 billion. Pantaloon's retail space will go up from 4 million sq ft to 30 million within four years. Spencer's, which has witnessed a seemingly incredible sales growth of over 100 per cent in the past 18 months, plans to add over 3,800 stores in the next five years.

Promoters who've been able to spot such opportunities—in telecom, retail and technology—have become billionaires. According to Business Standard's annual magazine, The Billionaire Club, the number of billionaires has nearly quadrupled in the last seven years—from 99 to 391. In just the past one year, the number has grown by over 20 per cent. Not surprisingly, over two-thirds of these entrepreneurs owned small and medium-sized businesses. Obviously, the recent market bull run has been a major factor in their cumulative wealth going up by 75 per cent in the last 12 months.

But this is just one side of this boom story. Apart from the billionaires and the millionaires, there are hundreds of millions who are below the poverty line, although their numbers are reducing. Another few hundred millions fall into the category of lower middle class; they comprise people who have lost jobs, youngsters who can't find new ones, others who are being pressurised to quit under VRS, and many who still find it difficult to live a reasonably comfortable life. For these people, the boom has no meaning—it's creating jobs for the elite, and enriching the pockets of the educated or opportunistic classes.

Reddy’s Lab, pioneered by Anji Reddy, above, gets 88% of its revenues from overseas markets, 50% from the US.

At the same time, policymakers are concerned about the possible overheating of the Indian economy. The country's central bank, theRBI, has expressed apprehensions about the rapidly rising real estate prices and has tried to curb lending in this sector. Similarly, analysts feel that Indian stock prices are probably "overvalued" and, at 14K Sensex, it's time for a correction. A below-average monsoon too can easily dent and stymie GDP growth. There are fears that inflation can easily spoil the rollicking party. Finally, a global slowdown—or one in the US economy—will stop the elephant's rock-n-roll.

Despite his unending optimism, Biyani himself sounds a cautionary note: "India doesn't have a designed direction as to what it wants to achieve as an economy. When the whole world—developed nations and others—is moving towards consumption, we're still talking about promoting savings. The country's design and direction is ordinary and there's often a myopic vision on a number of issues. In many cases, while solving a problem, we create a new one."

Hopefully, while growing at this breakneck speed, the economically backward, the have-nots, with neither hope in the future or faith in the system will not be just a blur in the rearview mirror.