On Bangalore’s busy Infantry Road, the most noticeable feature these days is the giant-size cutout of cine star Rajnikant in his latest maniacally frenzy-inducing flick, Sivaji. A group of youngsters at a cafe across the road though seem more interested in software codes, H1B visas, and the opposition in the US against outsourcing. It’s the changing mindset, and it’s reflected in the trail of leading global IT firms moving into India’s Silicon Valley.

A few hundred kilometres southeast of Bangalore, in Chennai, what strikes a visitor are the hundreds of white buses dotting the city roads. A closer look tells a story of the changing city. The buses are all leased/owned by Chennai’s IT companies, used to ferry employees on their unusual night shifts. Talk to young people on the streets and you realise software and technology is pretty much in their blood andDNA now.

The story is the same in Cyberabad. Far from the old city and close to Banjara Hills, abode of the rich and the famous, is Hi-Tech City. Just like the glass facades that stick out in the city’s otherwise old-world charm, there is a voluble, chirpy subculture on the rise. A different language is spoken here, one that’s easily understood by the Microsofts, Dells and Motorolas. The fact is, when it comes to setting up a facility in India, their search starts and ends in south India.

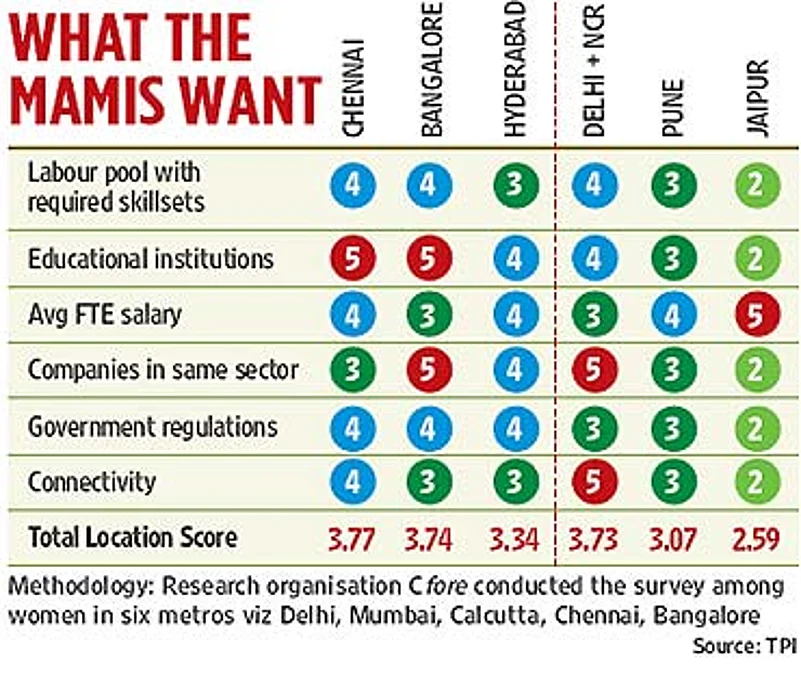

"If you have to come to India, you can’t get fired for choosing Bangalore, even at a higher price," says Prasad Ram, centre head (R&D), Google India. Adds Siddharth A. Pai, partner,TPI, a global outsourcing consultancy, "Companies go through significant analysis before deciding a location. This is based on parameters like availability of skilled people, accessibility from other centres, quality of infrastructure and government support. The southern cities have traditionally fulfilled them."

In fact, the south has emerged as the region with the best ingredients for any industrial/services clusters. For example, Bangalore has an innovation ecosystem for technology that can parallel Silicon Valley. For businesses, a lot of partners, like venture capital firms, incubation centres and consultants are also based in the city. The presence of leading academic institutions like the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) help in building a scientific environment that encourages research.

IISc Bangalore

The respective state governments have had more than their share in the success of these cities. Ex-CMs like Chandrababu Naidu (Andhra Pradesh) and S.M. Krishna (Karnataka) went out of their way to woo investment. Agrees Ravi Venkatesan, chairman, Microsoft India: "The state governments are extremely proactive. This attitude has remained despite changes in leadership." Adds Prabir Jha, senior V-P, Dr Reddy’s Labs: "While the IT industry put the flywheel in motion, the governments encouraged the development. Now there are efforts to develop smaller (southern) cities."

The knowledge story, though, began in the early 1980s, when Texas Instruments set foot in Bangalore, largely due to the availability of a talent pool in the city. S. Bhaskaran, senior director, Philips, agrees that "when we started our Bangalore facilities, it was because we wanted to be close to talent. Others have done the same. It’s the same effect as in Silicon Valley." Adds Susanta Misra, director, Hyderabad software centre, Motorola, "The social fabric in southern states stresses on engineering and science. So we see more engineers coming out of these states than from others."

Swati Piramal, MD, Nicholas Piramal, which recently set up a 1,000-member USFDA-certified centre in Hyderabad, says, "It was mainly the presence of good universities in the south that led us to establish this facility." Agrees Sarath Sura, MD, Sierra Atlantic, Software Services, an outsourcing product developer, "South India has a tradition of academics. Education has always been close to the hearts of South Indians. Parents of all income groups tend to ensure that their children are highly educated."

This is evident from the fact that there is an engineering college at every nook and corner in Chennai, which incidentally boasts of over 300 colleges. Bangalore has even more, 350, and Hyderabad over 200. A majority graduating from these colleges manage to find employment in their states as opportunities are higher. Bigwigs likeTCS, Infosys, IBM and Dell routinely recruit thousands of people every year. According to some estimates, nearly 25 per cent ofIITians come from Andhra Pradesh.

Microsoft—whose India Development Centre in Hyderabad mirrors its Redmond facility where product development, design, testing, and architecture are the thrust activities—recruits locally here. According to Srini Koppulu, MD and VP, a fifth of Microsoft’s employees are from Andhra, and others have been recruited from Anna University (Chennai),REC (Warangal) and BITS (Pilani). The Hyderabad centre is working independently on global offerings like RFID, mobile devices, virtual PC and Windows Vista.

Says Subhash Rao, director (HR), Cisco, "All of the top five cities are similar in infrastructure. It is the availability of people with suitable skills and experience that makes the southern states a winner. The people who started with traditional research institutions have formed the talent pool of today’s IT companies. In three years, 20 per cent of Cisco’s top talent, at all levels, would be resident in India."

This pool is becoming stronger due to another trend in Hyderabad. "Till a few years ago, IT in the city was basically bodyshopping. But now many Hyderabadis in their 40s, who went to the US 15 years ago, are relocating and finding the city a comfortable option for their businesses. The state’s policy is pro-education and plans are afoot to set up an XLRI and an IIT. This will help in nurturing more talent in the state," feels Sura.

Shanta Biotech, Hyderabad

What obviously helped the south was the society’s accent on higher education, which led to many national andPSU-driven research organisations to become based here. Post-Independence, many premier institutes like the Indian Institute of Science, and labs owned by public sector Hindustan Aeronautics, Bharat Heavy Electricals and Defence Research and Development Organisation came to be based in the region. It obviously helped create corporate-lab links.

Of course, more than this, it also created a technology sub-culture that established a partial commercial-driven research mindset. This also aided in global companies making a beeline to Bangalore, Hyderabad and Chennai, which provided world-class facilities for R&D. Explains a senior research head in an AmericanMNC, "The culture of Bangalore is close to that of international corporations. This helps while interacting with the outside world. Other cities have a very ‘Indian’ corporate culture."

Thanks to a combination of all these factors, the southern states are becoming innovation centres, rather than a mere outsourcing hub that’s largely driven by cost advantages. Says Venkatesan, "Earlier, it was cost arbitrage, but now no global company can have an innovation strategy without India being a part of it." Agrees Rahul Bedi of Intel, "What started as a cost-driver is today a talent-driver. Last year, much of the work on our Centrino Duo chipset was done in India."

For Motorola, over 50 per cent of its mobile phone software is developed at its Bangalore and Hyderabad offices. Says Motorola’s Misra, "We have gone up the value chain in R&D. Now we work on products from conception to commercial deployment. More ideas are generated in India for global applications and, globally, Motorola is critically dependent on what’s being done in India." Motorola’s India facility is its biggest outside the US and Misra, who holds the first patent developed by Motorola India, claims the India centre has filed for nearly 100 patents.

But this is peanuts when you consider Cisco Systems, which has filed for over 600 patents for products developed in India. And already, over 150 have been awarded to the company. Similarly, Philips India, has filed for 376 patents (and got 88) from its innovation centre in Bangalore. The lab has developed new global products like its new water purifier and the AmbilightLCD TV, which changes its backlighting coordinating with the on-screen colours. The Philips research head in India, SrinivasGutta, himself has 72 patents in his name. And he’s applied for 198 more!

Old warhorse IBM too has several patentable disclosures to its name in India. Their Bangalore R&D facility is probably the largest outside the US. Says Kalpana Margabandhu, director at the Bangalore software lab, "There are five product pillars thatIBM works on and only the India lab works on all five product lines." The importanceIBM attaches to its India operations is evident from the fact that last year IBM’s annual global meeting—which CEO Sam Palmisano has with institutional investors and industry analysts—was held in Bangalore, the first time it was held outside the US.

Some of the later entrants to the research arena in India are also now eyeing high-end work. Companies like chipmaker amd, which entered India two years ago, started with core development work. Says Deepanshu Sharma, GM (marketing and strategy), AMD, "Earlier, only low-level maintenance jobs came to India...but the value proposition has changed since then. ForAMD at least, critical work is happening here. The India centre is working on our quad-core chip which is truly cutting-edge research."

Still, even with all this, here’s one question in the subconscious minds of all these optimists: can Bangalore, Hyderabad and Chennai continue to drive global research and innovation? Also, these cities are getting crowded and expensive, so wouldn’t global firms be seeking alternative locations? True, the trend towards new research cities has started but no one’s still looking north. They are eyeing Tier II and Tier III cities in south India, Kochi’s Smart City being a major contender. But places closer to existing hubs still hold an edge.

Says TPI’s Pai, "Even in the search for smaller cities, south India provides more options. Not many north Indian locations can boast of such infrastructure. And typically, most companies look at the proximity factor with the existing hubs to set up new facilities." Adds Venkatesan, "With existing infrastructure and facilities in cities like Bangalore and Hyderabad, companies are now expanding around the corridors or beltways in directions that are close to these cities." Even when push comes to shove, when global firms feel they must look to go to a new city, it’s in the southern states only.

So while there is some activity in the Mumbai-Pune corridor, and in Delhi’s National Capital Region, most of the new names being bandied about are Mysore, Hassan and Hosur, which are accessible from Bangalore. Other places include the Dharwad-Hubli twin cities in Karnataka, Coimbatore and Madurai in Tamil Nadu, and Vizag in Andhra Pradesh. Even domestic giants are setting up campuses in these new cities.

The only caveat: infrastructure will need to come up really fast in the newer innovation centres. Or the state governments will have to quickly beef up infrastructural gaps in Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad. The millions of residents in these cities would definitely agree with that part.

by Arindam Mukherjee and Madhavi Tata