- In the past few years, over 4,000 farmers have killed themselves, trapped in a vicious cycle of debt, crop failure and penury.

- Nearly half of Indian farmers are gripped by debt. 82 per cent of Andhra's farmer households are indebted; it's 74.5 per cent in the case of Tamil Nadu.

- While agricultural incomes are rising by only 1.5 per cent, consumption expenditure is going up by almost 4 per cent.

- The total short-term credit required for crops is about Rs 1 lakh crore a year. Financial institutions supply only 12-14 per cent of this.

- The share of long-term credit to agriculture declined from over 20 per cent in the 1970s, to 15 per cent in the 1980s, and to 12 per cent in the 1990s.

- From 16.4 per cent in 1979-80, plan outlay for agriculture slumped to 6 per cent in the 1980s, and to 4.9 per cent in the Ninth Plan (1997-2002).

Surrounded by other neighbours—all widows—P. Sunitha of Nalgonda, Andhra Pradesh, braves the blistering May heat to sit on dharna with her two-year-old son, clutching a photograph of her husband Rangaya hanging from the rafters of their hut. In the past few years, over 4,000 farmers, many from the cotton and dryland belt of Andhra, Maharashtra, parts of Kerala and Punjab, have killed themselves, trapped in a vicious cycle of debt, crop failure, penury and extreme hopelessness.

Rangaya, a chilli farmer, took his own life after his crop failed for the second year. "Two years ago, he borrowed Rs 20,000 for a borewell. The well dried up, he took a second loan, but no water this time too," says Sunitha. Rather than face humiliation at the hands of the moneylender, Rangaya took the silent way out.

Punjab, Andhra, Maharashtra. Prosperous states with a rich output of food as well as commercial crops. Industrially vibrant, politically aware, technologically and financially up-to-date. Yet, in their villages, the soil in places has cracked to a spider's web, the skies are unyielding, the water that flowed so noisily has dived deepinside. And the helpless tillers of the land, the faithful sons of the merciless soil, are succumbing to a tempting longnoose. Or to pesticides that proved so ineffective at their real job.

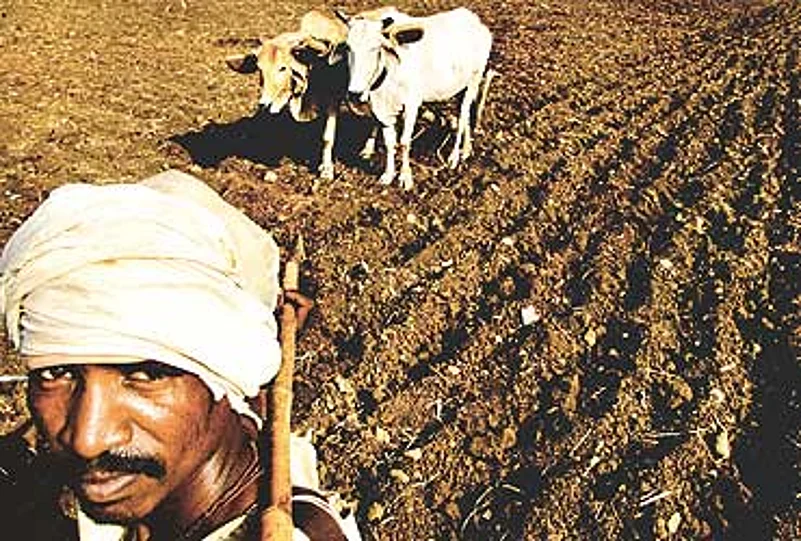

Sitaram Mali, Village Loni, District Yavatmal, Maharashtra : This farmer may have his own three acres of land but he also has a loan of approximately Rs 40,000 on his head pending for the last 3-4 years. To make ends meet, Mali works as a labourer in someone else’s field at Rs 45 a day.

Repeated crop failures, overcapitalisation of farming, costly inputs and implements, lack of electricity, inadequate irrigation, increasing fragmentation of land holdings...many reasons, one solution. Indian agriculture, which contributes a quarter of the gdp and is a source of income to 60 per cent of our people, is getting increasingly risky, expensive and water-dependent, driving the farmers even in rich states like Punjab (see box) to a riskier remedy: more and more credit.

An Indian farmer household has an average debt of Rs 12,585, says a recent survey by the nsso (59th round). The Punjab farmer tops the list with Rs 41,576, followed by Kerala with Rs 33,907, Haryana Rs 26,007, Andhra Rs 23,965 and Tamil Nadu Rs 23,963.

Nearly half of Indian farmers are gripped by debt. Half of them again belong to five states—UP, Andhra, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh. But in relative share, Andhra tops the list with 82 per cent of indebted farmer households. Tamil Nadu follows with 74.5 per cent and Punjab, 65.4 per cent. More than half of them have taken loans for capital or current expenditure in farm business. Marriages and ceremonies are the next major cause—11 per cent. Banks lent the maximum—36 per cent—followed by moneylenders with 26 per cent. Scheduled caste and other backward caste farmers were the worst off.

Says Dr Ramesh Chand, acting director,NCAP, Pusa: "Indian agriculture is heading for a crisis. We have been debating reforms for long, but there are hardly any decisions and implementation. There is too much degradation of natural resources. There is still no proper institutional mechanism that allows farmers to sell their produce freely. So, income growth has slowed down and credit is not translating into asset creation of similar value. While consumption expenditure in the agrarian economy is rising by up to 4 per cent, incomes are going up by only 1.5 per cent. The resulting gap is increasingly met by credit."

He's right. The share of non-food items in the rural consumer basket has grown from 26 per cent in 1969-70 to 41 per cent in 1999-2000 and perhaps close to half by now. Even credit availability is up, from 10.8 per cent of total credit supply in the '70s, to 15.5 per cent in 2001-02. But the number of farmers tapping institutional channels like banks and Nabard is still very low.

Says Prof Ajay Dandekar of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) who headed the study on farmer suicides in Maharashtra at the request of the high court: "The chasm is huge. The total short-term credit required for crops in India (crop loans) is about Rs 1 lakh crore a year. But financial institutions supply only 12-14 per cent of this."

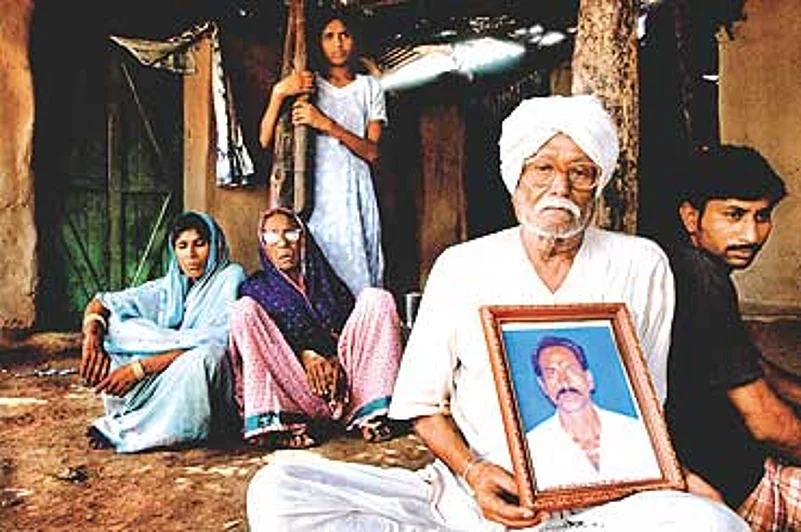

Shamji Turi, Village Pandhri, District Yavatmal, Maharashtra: Shamji holds the photo of his son Govind who took his life on June 25 last year as cottonproduce from his 2 ha of land declined steadily. Saddled with a debt of Rs 55,000 and with four daughters to marry off, Govind opted for death.

Even thinner is the access to credit for small and marginal farmers—marginal farmers have a landholding size of less than 1 hectare and small farmers, 2-4 hectares (semi-medium and medium—4-10 hectares; large over 10). A 2004RBI study for Andhra and UP, our biggest borrowers, proves it. While 24 per cent of all Andhra farmers have access to formal credit channels, only 12 per cent of marginal farmers were so lucky. The numbers for UP were 19.4 per cent and 13.5 respectively. An average holding in India is just about 1.4 ha in size, and only 15 per cent of farmers can be called large.

According toRBI, the share of long-term direct institutional credit to agriculture fell from over 20 per cent in the '70s to 12 per cent in the '90s. Short-term credit was stagnant at around 14.5 per cent. Even now, banks typically go in for large loans, ignoring repayment capacity and quality of loan.

And this credit comes with strings attached. A defaulter, even for natural reasons like crop failure, never gets another loan. Even kisan credit cards, which have a limit of Rs 5,000 per acre, are not reusable unless the borrower has repaid the first loan inpart/full. The reason for such circumspection is not clear because non-performing assets (bad debt) of public sector banks due to agriculture sector was only 14.4 per cent in 2004, compared to 17.6 per cent due to small industries. And the small, voiceless farmer is the one most impacted by this policy of abundant caution.

Mansaram’s family, Village Marocha Iswari Singh, Barabanki, UP: Cheated first by the middleman who took away the tractor his father had bought on a bank loan and then returned an old one; this also wasauctioned along with sale of pledged land for loan recovery. Mansaram hanged himself.

The final report of the TISS study notes: "There is a general crisis of credit in the agrarian economy, reflected more in the medium and small landholdings. The debt trap is due to the inadequate credit supply to the cultivators at an affordable price and due to the rising costs of production that cannot be met."

Says 45-year-old Siddaramaiah, who owns six acres of land in Kenchanguppe village on the way to Mysore: "I invest over Rs 20,000, but recover only Rs 12,000. This Rs 8,000 is a recurring debt. When it becomes too big, we sell a bit of land. The banks have become very strict. You have to plead with the localMLA or a zilla/taluk panchayat president. The politics is disgusting."

As a result, the village loan shark, whose pincer-grip the banks with their priority sector mission were supposed to replace, has thrived with his 20-35 per cent interest rates. Today, these are mostly the commission agents (a respectable term for middlemen) who arrange everything for the unlettered farmer—selling produce, securing a bank loan, procuring modern seeds, and so on. They also act as agents for tractors, seeds and pesticides, often giving wrong advice. (Dr Chand says a tractor is an unnecessary expense for a farm of less than five acres.)

Says Dr Surjit Singh of the Institute of Development Studies, Jaipur: "If merely availability, and not cost, was the problem, the moneylenders would have developed the rural sector long ago. The small farmer operates under a low level of equilibrium, hence there is the danger that raising the cost of credit by even 2-3 percentage points may convert the viable to the unviable. A farmer who cannot afford the cost of exploiting his land rationally by applying fertilisers and pesticides cannot expect high returns. Credit has no place in subsistence farming."

Singh should know, the son of a farmer with 24 acres of land in Punjab. "When I appeared for the PhD viva, I was asked why I rejected a farmer's life. What a question! Already, this land is divided between my brother and me. And my father, the diehard farmer that he is, is happy that he's getting Rs 50,000 every year from his fields. If Indian farmers started doing a cost-benefit analysis, half of them would prefer doing odd jobs in the city".

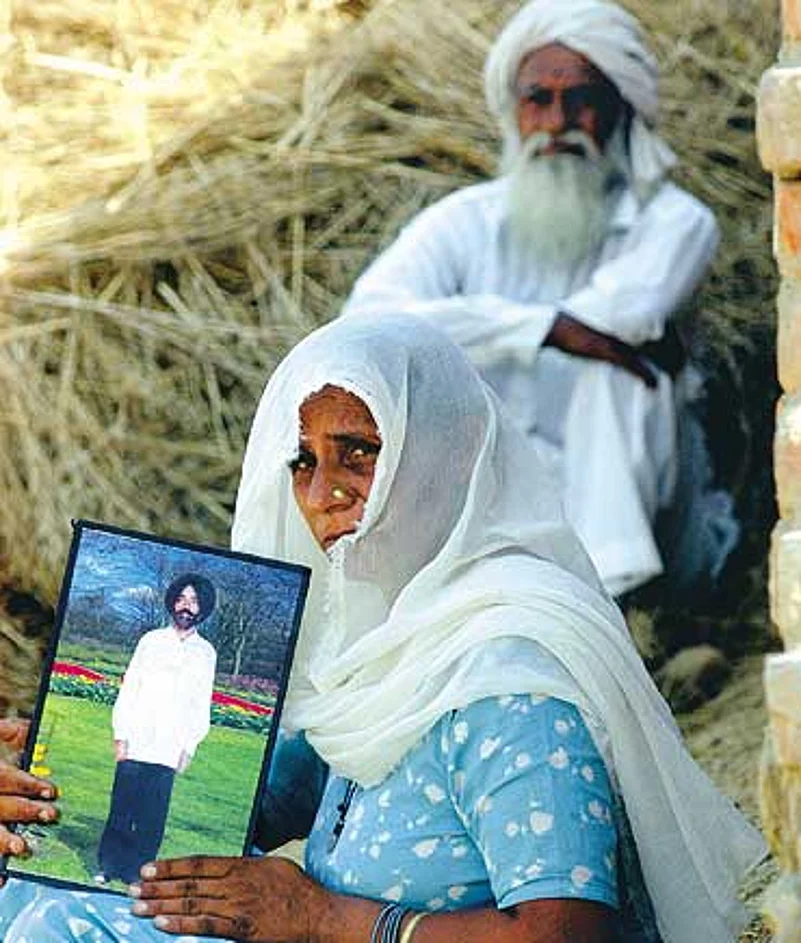

Jaswinder Kaur, Village Jawaharwale, District Sangrur, Punjab: She lost her husband Diwan Singh to debt in 2003.Says she, "We do not have the money to sink deep tubewells. But the outsiders who are buying up our land are putting them in. We are labourers on our own land now."

Yet, despite several commissions and RBI reports, the Centre and state governments (agriculture is a state subject) have remained deaf to the farmers' collective woes—we say collective because small and marginal farmers make up 60 per cent of the total 100 million farmers. The decline in agriculture started with the decline of public investment in the sector—in irrigation, marketing infrastructure like warehousing, mandis, etc, and seeds and extension services. This began in the '80s, coinciding with theIMF loan. From 16.4 per cent in 1979-80, plan outlay in agriculture and allied activities slumped to 4.9 per cent in the Ninth Plan (1997-2002), making farming, always the most privatised, independent business, a totally support-less venture in these liberalised, globalised times. The skewed pricing policy allowed production to concentrate either on water-heavy paddy and wheat or commercial crops whose prices fluctuated with global market movements.Yet, states still don't allow free movement of grains among themselves.

Says Vijay Jawandhia, president, Maharashtra State Cotton Producers' Organisation: "After globalisation, input costs increased but price of produce fell. This was a double blow. While US cotton producers enjoy a subsidy of $4 billion, we have imported over 100 lakh bales of cotton post '95.A 'khandi' of cotton fell from Rs 22,000 to Rs 16,000 over the past year, hitting the growers naturally, but even the consumers did not gain." While politicians catered to isolated farmer lobbies, keeping their stranglehold on land intact, Indian farming, already a victim of fragmentation and irregular rains, inched close to disaster.

Siddaramaiah, Village Kenchanguppe, Mysore, Karnataka: This 45-year-old has six acres of his own land. But his despair is evident when he says, "We spend half our lives hoping for a good monsoon. When we have one, we don’t get the prices we expect. Agriculture is not at all profitable."

Adds P. Chengala Reddy, Andhra MP and farmers' leader: "Lack of irrigation facilities and total dependence on erratic rainfall has pushed the state to the top of the list of rural indebtedness. Especially for AP farmers tempted by high-value crops like cotton and chilli." In the past decade, thousands of small and marginal farmers have turned wage workers on their own land. Utkarsh Sinha, farmers' activist in UP, says farmers raising cash crops—sugarcane, potato and wheat—are usually debt-ridden. Middlemen take away over half of what these subsistence farmers manage to make. Yet, few states barring Karnataka have amended their Agricultural Marketing Acts to allow private buyers.

Says Dr Singh: "The two-volume Rajasthan 10th plan document contains just a para on drought-proofing. Imagine this in a state where oilseeds and bajra, both rainfed crops, are staple." Bengal, which took pride in its land redistribution of the '80s, is now reporting starvation deaths. Kerala is underNHRC pressure to investigate farmer deaths. Even Karnataka is reporting suicides. Banks now treat infotech as a priority sector, while farmers borrow and toil their way to disaster not having recourse, like industrialists, to debt recovery acts or insolvency declaration.

Sums up young Girish from Guddehalli village, Chikmagalur, Karnataka: "It requires a lot of money to do farming. And then there's no guarantee of rains. We are not cultivating anything on our land now." To repay his accumulated debt, this part owner of 50 acres of family land is driving a taxi in the city.He's better off without the tension and humiliation. Smiles Girish, sadly: "Farmers have loans on everything, the ox, the bullock, the implements and also on their own sweat."