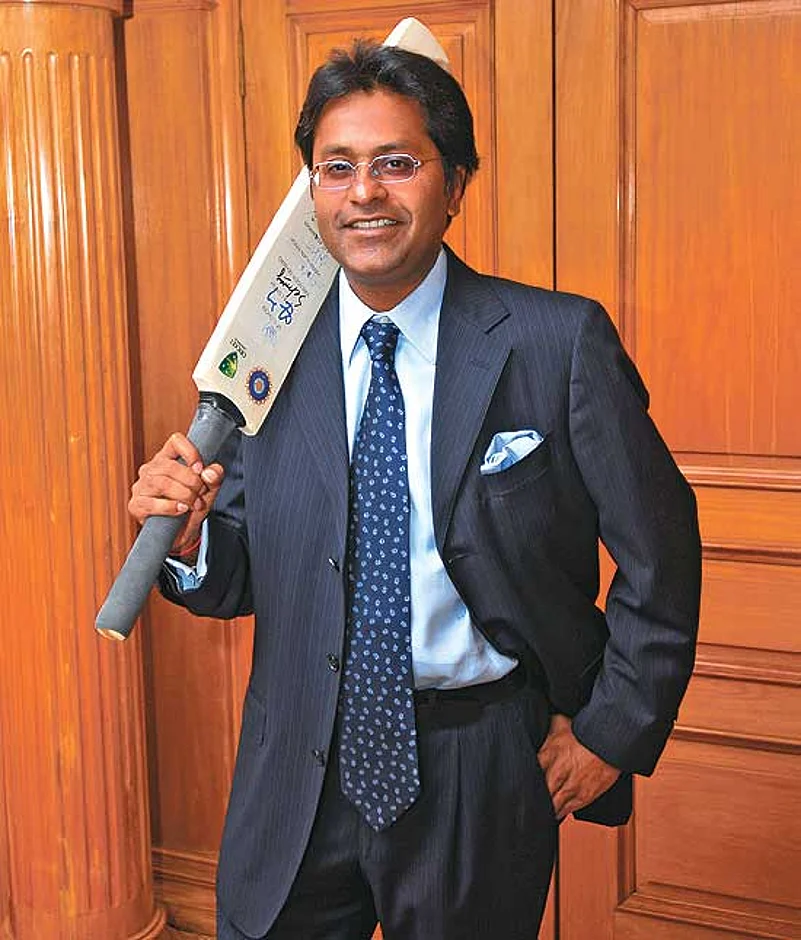

When Lalit Modi rose to speak at the magnificent celebration of his parents’ 50th marriage anniversary in Bangkok in the last week of August, he didn’t indulge in the grandiloquence of his days of glory and infamy as IPL commissioner. He was among family and friends, people who know him really well. He spoke briefly, from the heart. Modi, according to a guest, said he’d been always in some sort of trouble all his life, right from his childhood. He thanked his parents for supporting him and extricating him from trouble through his life.

But it’s unlikely that even his father, K.K. Modi of Modi Enterprises, can save his son from the clutches of law, if and when he does return to India. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) is closing in on him, seeking his presence to answer questions over FEMA (Foreign Exchange Management Act) violations and even the possibility that he had been laundering money into two IPL teams, Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab.

The BCCI has suspended its contract with the two teams. It’s also lodged a police complaint against Modi “for criminal misappropriation of BCCI funds totalling Rs 470 crore”. The annulment of Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab has sent the cricket world into turmoil and Modi into a rage—but only on Twitter.

There are no signs of Modi returning to India to wage battle defending his innocence and establishing the guilt of his enemies who, as he said before leaving, were hell-bent upon destroying the IPL. There are enough indications that Modi, actually, wants to make a home in another country. A source familiar with Modi’s movements over the past several months says, “He’s been trying to get some sort of residency in Panama or Iceland. But it’s likely to be Iceland.” There’s a good reason for that, he says. The first lady of Iceland is Dorrit Moussaieff, a Jerusalem-born UK citizen from a family of famous jewellers. Growing up, she and Minal, Modi’s wife, lived in the same apartment building at Grosvenor Square in London. “They’re childhood friends, and Modi’s trying to use that connection to get residency rights in Iceland,” he says.

For His Sake: Zuma, a Japanese restaurant in London, where Lalit Modi is often seen

Modi, it’s learnt, is keeping a low profile in London, but he has been making vigorous efforts to get in among the upper crust of British society, and Mark Shand—the brother of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall—is a favourite of his in this enterprise. Says another source, “He’s been trying to get thick with businessmen of Indian origin.” Modi lives in a rented apartment at Cadogan Square and has brought his home staff from Mumbai with him. He’s frequently seen at two well-known restaurants: Zuma, a Japanese restaurant owned by an Indian family of Sindhi background well-known to Modi’s wife; and China Tang, a Chinese speciality restaurant. There’s a family connection here too. The K.K. Modi Group has acquired the India franchise for a luxury brand, Shanghai Tang, launched by China Tang owner David Tang.

Modi’s son Ruchir, who’s opted out of the exclusive Le Rosey school in Switzerland, has joined the American School at St John’s Wood with help from Shand. Sources say Ruchir isn’t proving to be a very popular scholar. “He went to school wearing an extremely expensive watch and was reprimanded by the principal for it,” says a source.

Modi has been travelling around Europe—his private plane is usually parked in London—to ensure he does not qualify as a resident of the UK, and therefore liable to be taxed. And though he’s been citing a live security threat against him as the reason why he has evaded questioning in India, this hasn’t prevented him from taking pleasure trips. He was spotted in the south of France recently, and at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza last month. At Monza, those who met him did detect an air of embarrassment around him, now that the government authorities—and not the BCCI—are keen to have a word with him.

Modi is a frequent guest of his friend Vijay Mallya, owner of Bangalore Royal Challengers, who has been critical of the BCCI’s recent move. “What else would Mallya do?” asks a senior board official. “He’s a friend of Modi’s, and if Modi had been around as commissioner, it would have only helped Mallya.”

Clearly, the BCCI wasn’t looking to resolve the issue of FEMA violations through conciliatory measures, acting decisively as it did against the two teams thought to be guilty. The ED believes Modi was laundering money into IPL through his nri relatives who invested heavily in the Punjab and Jaipur teams via off-shore firms. In case of a dispute, there’s provision in the agreement between the BCCI and the IPL teams for resolution through arbitration. “The BCCI resisted that,” says a Rajasthan Royals source. “Even if there was violation of laws, the penalty is to be imposed by the authorities, not by the BCCI! Why wasn’t action taken against Kolkata for similar offences?”

An official with another franchisee says that apart from Mallya, there’s no anxiety among the others about the IPL. “It’s clear the agreement with the BCCI was violated in a serious manner,” he adds. “The bid was made by someone, someone else became the owner, and then they changed the ownership pattern more than once. The BCCI can terminate the contract—it’s clearly stipulated.”

BCCI president Shashank Manohar did indicate in May that things would come to such a pass; and as Modi’s ship listed dangerously, the rats fattening in its depths started abandoning it. The most adroit turnaround was made by Sundar Raman, IPL’s CEO. In May, asked what he thought about Raman physically pushing around Delhi Daredevils official and former cricketer Sunil Walson, Manohar had said that he was “behaving like his boss (Modi)”. Raman got the message, is giving evidence against Modi, and, no wonder, retains his job.

The belated action against Modi and the two teams hasn’t absolved the BCCI of its share of blame—why did it not detect the illegal activity earlier? “All our decisions were communicated to the IPL and the BCCI,” says a Rajasthan Royals source. “These very people who’re in the BCCI were on the IPL governing council then. How’s it that they find problems now?” Adds lawyer-activist Rahul Mehra, “You can’t take such a decision without giving the other party a chance to be heard. They have no option but to go to court over this.”

But Modi seems to be getting a taste of his own medicine. When he was part of the BCCI, he didn’t see any problem in India Cements—in which secretary N. Srinivasan is a majority stakeholder—owning an IPL team. Now, in trying times, Modi is crying his heart out over this obvious conflict of interest. But it’s obvious wars aren’t won in absentia, certainly not by flailing about on Twitter. Modi needs to join battle at home—a remote possibility for a self-exile who wants to set up home in an icy, foreign land.