A Sorry Cradle

- 1,830 India

- 1,077 Nigeria

- 554 DR Congo

- 465 Pakistan

- 365 China

- 321 Ethiopia

- 311 Afghanistan

Annual number of deaths under 5 years (in thousands)

***

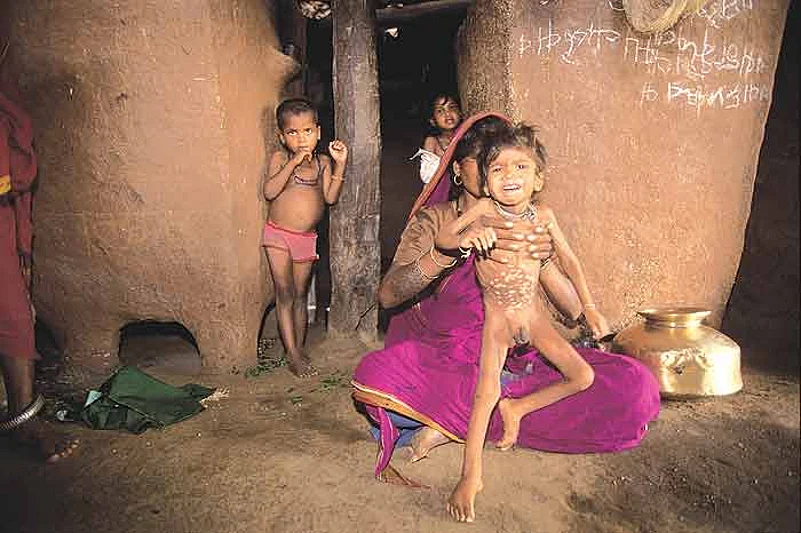

Last week, the central government celebrated five successful years of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and its outreach programmes. But an international report from the voluntary group Save the Children, to be released on May 3, comes as a dampener. The figures show India topping the global list for child mortality under five years. Nearly 20 lakh children die every year, 50 per cent of them in their first month. Most of the deaths are preventable.

Only a few years ago, there had been an improvement in child mortality. The current worsening indicates the healthcare system and the NRHM are not delivering expected results. What’s worse, India tops in another notorious statistic: neo-natal deaths, or those taking place within four months of birth. Experts say this is a primary indicator of a failed health delivery system. Under-5 mortality rates show dramatic rises when:

- Mothers get little or no pre-natal care

- Deliveries take place without access to medical support

- Infants aren’t breast-fed

- Children aren’t immunised

- Childhood diseases go untreated

The main causes of children’s deaths in India are pre- and post-natal conditions, lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhoeal diseases, malaria, measles, congenital anomalies, HIV/AIDS, tetanus, and protein malnutrition. According to health officials, simple intervention can prevent 90 per cent of diarrhoea-related deaths. Similarly, fatalities caused by other diseases can be substantially reduced. Keeping the newborn sufficiently warm, neo-natal resuscitation, regular intake of micronutrient supplements, using antibiotics for sepsis, pneumonia and dysentery—these are considered effective interventions for keeping mortality rates in check.

“Fifty per cent of deaths under the age of five are neo-natal deaths, and some 4 lakh children die within 24 hours of being born,” says Shireen Miller, director of advocacy for Save the Children. “Critical care for newborns and mothers during this period is not being done.” And Dr Aparajita Gogoi, national director for the White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood, an American NGO, says what is most disturbing is that a large number of these deaths can be prevented. “If communities and families are provided information on breast-feeding and not bathing the newborn for the first 5-6 days, and if the government implements some very lowcost interventions, there will definitely be a huge drop in the infant mortality rate,” she says.

The report, titled ‘Women on the Front Lines of Health Care: State of the World’s Mothers’, identifies countries that have invested heavily in training and deploying more female health workers to deliver care to the poorest mothers and babies. India’s neighbour Bangladesh has been doing this effectively. There, female community health workers with just six weeks of training are estimated to have contributed to newborn mortality reduction of 34 per cent and deaths under the age of five by 64 per cent. “Bangladesh has done much better than India in reducing its infant and maternal mortality rates. India needs to focus on its worst-affected areas. There are particular districts and tribal areas where the number of children dying is very high and the government is failing to target these. India has not tried to reduce its infant mortality rate in many years,” says Miller. “For neo-natal deaths in 1992, it was 49 deaths in every 1,000 births. Now, after nearly two decades, it’s 39 deaths in every 1,000 births. There is a huge shortage of health workers; the government needs to address this more seriously.”

Worldwide, there are 57 countries with shortage in the workforce meant for critical healthcare. India is among them.

In its latest update, the government says it is short of 74,000 accredited social health activists (ASHAS) and 21,000 auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMS). “While the NRHM has done well in areas such as institutional deliveries, post-natal care needs more resources,” says a senior health ministry official. “We are facing a huge shortage in manpower and this could be affecting the childcare programmes in different states.”

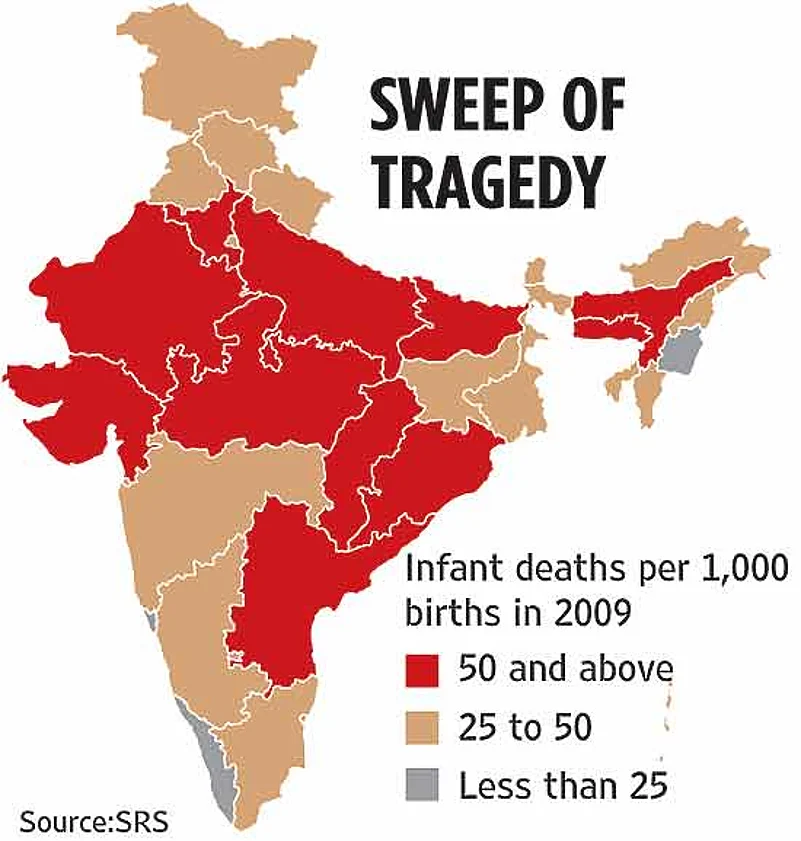

The recent CAG report on NRHM highlights the huge shortfall in health workers. It says institutional deliveries and immunisation have increased, but most women registering as pregnant are not going to health centres for delivery. ‘Micro birth plans’ and cards, meant for registered pregnant women so that they get all the benefits of the institutional delivery programme, have not been prepared in most states. More importantly, the CAG report notes the absence of a proper mechanism for collecting data on neo-natal deaths in the audited districts of 17 states. India’s current infant mortality rate is 53 (per 1,000 births) and the government wants to bring this to 38 by 2015. To work towards that, states have been conducting immunisation camps and special programmes for newborns along with midday meals to combat malnutrition.

The states with the highest infant mortality rates are Assam (64), Rajasthan (63), Uttar Pradesh (67) and Orrisa (69). These figures are all above the national average. The states with low infant mortality rates are Kerala (12), Goa (10) and Manipur (14). While the health ministry has assured Parliament there is no shortage of funds for implementation of childcare programmes, global health watchdogs are questioning the impact of its programmes and their effectiveness. After all, there’s no denying that 20 lakh children died in India this year.