- In peak season, 5 lakh devotees visit the shrine every day

- The Pampa river is heavily polluted. State pollution board studies says the river water is of sewerage grade.

- Plans to develop infrastructure have been hanging fire for decades

- Experts say priority should be the setting up of a 3 MLD sewage plant

- Pilgrim facilities should be moved a few kms away to reduce congestion

***

The story is typical of modern, pan-Indianising trends. Ayyappa as a deity has a strong local flavour—though his birth is assigned to the union of Shiva and Vishnu (in his female avatar, Mohini), he was specific to Kerala and proximate areas of Tamil Nadu. But over the years, the hill shrine has grown in esteem well beyond this original radius. The throng of devotees, typically clad in black and in a reverie punctuated with almost slogan-like incantations, swells more and more each year. During the two-and-a-half-month-long main season, as many as five lakh pilgrims take the 5 km trek from the Pampa base station to the sanctum sanctorum, at an altitude of 4,135 ft, everyday. A 20 per cent increase has been noticed in the number of bhakts year on year in recent times. Unfortunately, the infrastructure at the shrine has not kept pace and is now struggling to cope with the rush.

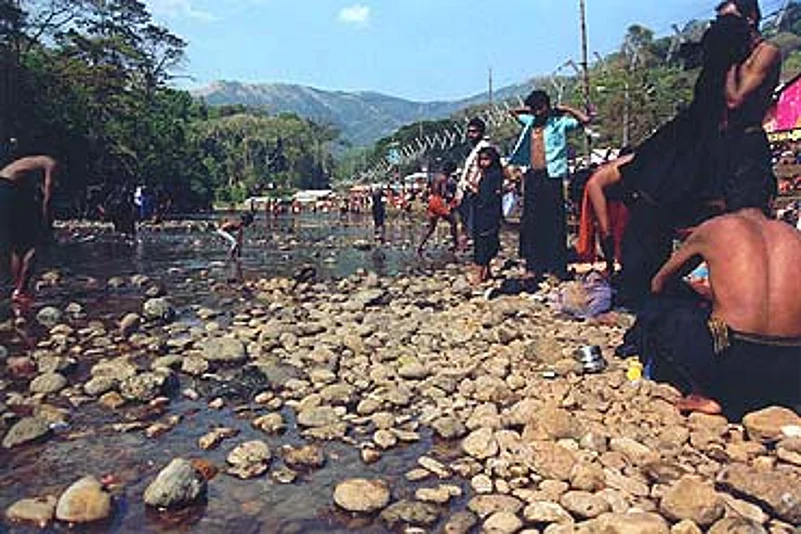

The worst hit is the Pampa, or the 'Dakshin Ganga'. Nowadays a dip in the river—an integral part of the pilgrimage—is by all estimates a health hazard. During peak season, faecal coliform bacteria count is at an alarming 60,000 per 100 ml (as against a permissible upper level of 300/100 ml), says a 2006 study by the Kerala State Pollution Control Board. Unsuspecting pilgrims still savour it, after all it's teertham (holy water).

Garbage—empty bottles, plastic packets, leftovers and what have you—is routinely dumped into the river. However, the main source of contamination is the "overflow from latrines" that line the steep terrain along the riverbanks. Even at the sanctum sanctorum, the sewerage drains into a part of the hillock and gets washed downstream into the Njunangar rivulet that joins the Pampa.

Why is the situation so bad? The Travancore Devaswom Board, which runs Sabarimala and 1,200 other temples in Kerala, is flush with funds. Sabarimala's revenue last fiscal was Rs 100 crore, so that's no excuse for not developing the infrastructure. Several projects have been hanging fire for decades now. The Centre had okayed a Pampa Action Plan, involving an investment of Rs 319.70 crore, in '02. This was to be finished in three phases: the Pampa was included in the National River Conservation Programme. It had top priority since the Pampa is the main source of drinking water for 30 lakh people living downstream, up to Kuttanad in the coastal Alappuzha district.

But it stayed on paper. N.K. Sukumaran Nair of the Pampa Parirakshana Samity, an NGO working to save the river, is bitter. "Precious little has been done even on the initial listed work, estimated at Rs 13 crore. This involved construction of toilets, sewage treatment plants and drains as stipulated," he says.

After a four-year delay, the first phase of the Pampa Action Plan finally kicked off this May with work on three check dams across the Pampa and two other streams. But one dam was washed way in the monsoon rains. Incidentally, construction of the shutter dams across the Pampa is to check the sewage flow through the Njunangar rivulet.

Choked gills: Devotees and the Pampa

Experts fault the whole plan. They say priority should have been accorded to building a three million litre per day (MLD) sewage treatment plant at Sabarimala and a 1.5 MLD plant at the Pampa. Sukumaran Nair says a "lack of coordination among government departments and the absence of an independent implementation agency have botched up the work." Whatever little has been done, he says, owes to the efforts of T.K.A. Nair, principal secretary to the PM. The latter, who hails from Pathanamthitta district where Sabarimala is located, had suggested setting up a state-level nodal agency, the Pampa River Basin Development Authority (PRBDA), to implement the integrated Pampa Action Plan. But the project got clubbed with the ambitious mega Sabarimala master plan to develop the shrine into a pilgrimage tourism centre. As a result, there's been little forward movement in cleaning up the river.

Experts say the 250-acre Devaswom land at Nilakkal, 12 km downhill from the Pampa base station, must be used to set up a proper complex with comfort stations and other amenities to reduce congestion at the top. But no one seems in any hurry. Says a Devaswom official: "It'll be difficult. There's commercial interest in ensuring there are crowds at the two places where all the lodges and restaurants are located. Shifting them elsewhere would hit the hoteliers."

To add to all this is the Travancore Devaswom Board, which may not be short on funds but is in every other way a complete mess. Board president C.K. Guptan, son-in-law of late Marxist titan E.M.S. Namboodiripad, is at loggerheads with the other two members of the three-man committee—ironically, nominees of the CPI and RSP, allies of the ruling Left coalition. The government now plans to increase the number of members, pack the board with CPI(M) men so that the president can have his way.

Guptan admits to problems in Sabarimala, but does not subscribe to the idea that a panel of bureaucrats, with proven track record, run and manage the shrine. "What if they turn out to be corrupt?" asks Guptan. The next season, he vows, will be more hygienic. Guptan can take comfort from the fact that, as a rule, the demand for development dies down after the pilgrimage season ends. And January is not that far off. What of the Pampa and the poor pilgrims, though?