The premise that Islam is something that can be a closed or an open religion may not be the best one. Islam, in its many forms, methods and practices, is a reflection of the person who practises it (just like any other religion). If your view on dealing with other people and their faiths and intellectual backgrounds is rigid and closed, then your practice of Islam or whatever faith you practise will also be rigid and closed. There are innumerable ways to approach one’s spiritual relationship and so the question will be whether those who claim to be adherents of Islam will take a rigid approach as opposed to an ostensibly open one. That is a function of many issues—economic, social, cultural and, of course, political. In societies where we perceive Muslims as being closed, they are often subject to repressive regimes (both secular and religious) where their closed practice of Islam is highly correlated to the nature of their rigid society, with limited basic freedoms (expression, speech and, yes, even religion).

Those who are making such closed/open claims about Islam are liberals, and liberalism has always been associated with racism, authoritarianism, extreme violence and efforts to destroy non-European ways of life. Muslims, like other non-European peoples, have always been targets of liberal violence, and they have responded to defend themselves, albeit not always in the most appropriate or ethical of ways.

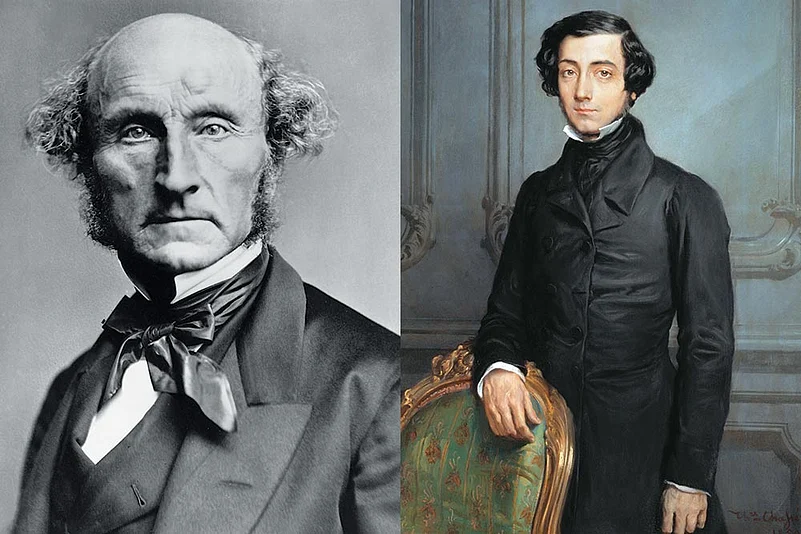

John Stuart Mill (1806-73) is the leading theorist of liberal imperialism and the civilising mission. Mill spent his life employed as a high-ranking officer for the British imperial regime in India, where he formulated policies to govern the subcontinent’s Muslim and Hindu communities. Mill argues for placing non-Europeans under dictatorships in the form of imperial rule (i.e., “despotism”). These dictatorships exercise their power to compel adoption of western civilisation. Championing this policy, Mill remarks: “There are…conditions of society in which a vigorous despotism is in itself the best mode of government for training the people in what is specifically wanting to render them capable of a higher (i.e., western) civilisation.”

Mill goes on to make another important point: dictatorship (despotism) need not be applied by an outside country. It can also be applied within a country by the civilised elite. In these circumstances, a ruler drawn from the elite should govern through dictatorship for the purpose of coercing the masses to adopt western civilisation. Put differently, the ruler should use dictatorship to undertake a civilising mission. Hence Mill remarks, “The case most requiring consideration in reference to institutions is the not very uncommon one, in which a small but leading portion of the population, from difference of race, more civilised origin or other peculiarities of circumstance, are markedly superior in civilisation and general character to the remainder. Under these conditions, government by the representatives of the mass would stand a chance of depriving them of much of the good they might derive from the greater civilisation of the superior ranks.”

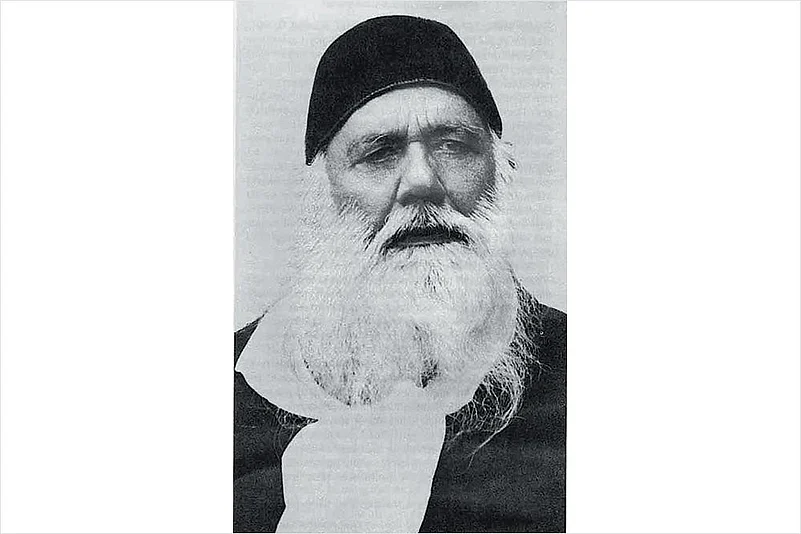

Historian Mohammad Sajjad rightly observed: “Sir Syed (Ahmed Khan) is relevant today for his rationalist enquiries and engagements…. (He) took to writing rebuttal and refutation of William Muir’s expositions against the Prophet. Unlike today’s hard-headed radicals who don’t know how to engage intellectually and resort to ominous violence, Sir Syed hated pan-Islamic, extra-territorial loyalties, and believed that India could march ahead only with its polychromatic character and inter-faith harmony. He instituted scholarship exclusively for Hindus in his Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College, to make its enrolments heterogenous. He did not allow beef in the hostel mess of Aligarh College. He campaigned for free press to build modern India. He braved the ire of conservative clergy”.

The liberal notion of imposing western civilisation through imperial rule licenses European warfare across the globe, and opens the door to the wholesale destruction of non-European religious and cultural traditions (including Islam). These issues are taken up by the political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-59), arguably the most celebrated French liberal of his era. Tocqueville was a member of the French parliament and frequently corresponded with Mill on political matters. Like Mill, Tocqueville was a staunch proponent of imperialism, championing the French conquest and colonisation of Muslim Algeria. He travelled to Algeria in 1841 and 1846, becoming the French parliament’s leading expert on Algeria and a key policy-maker on Algerian issues.

John Stuart Mill (left), theorist of the civilising mission; Alexis de Tocqueville, who told the French parliament in 1840 to let France participate in military campaigns in the Orient

Speaking before the parliament in 1840, Tocqueville addresses the role of French imperialism in the Orient, including the Muslim world. Tocqueville argues that France, like Britain and Russia, must take part in military expeditions in the Orient, establishing its power, while destroying indigenous religions and cultures and replacing them with European civilisation. He compares Europe’s current military expeditions to the Christian crusades against the Muslim world, but asserts they are far more intense and destructive. “I do not like war, I just said it; but there are extreme situations in which war would appear to me a benefit; and I believe it is my duty to declare these extreme situations in front of my country,” writes Tocqueville. “There is one extreme situation that one should escape even by war. It would be to abandon from now on and forever the hope of playing any role in the question of the Orient. You will answer me. Great things have been said about the question stirred up this moment on the banks of the Bosphorus, but we have not said anything; what is happening in Egypt and Syria is only the edge of a giant picture, it is only the beginning of a vast scene. Do you know what is happening in the Orient? It is an entire world which is being transformed. From the banks of the Indus to the shores of the Black Sea, in this giant space, all societies are being shaken, all shaking, the religions are fading away, all nationalities are disappearing, all the lights are going out, the old world of Asia disappears; and in its place we see a European world gradually arise. Nowadays, Europe does not only accost Asia through a corner, as it did at the time of the Crusades; Europe attacks Asia in the north, the south, the east, and the west, from all sides; Europe puntures Asia, envelops it, subjugates it. Do you believe a nation that wants to remain great can attend such a show without taking part in it? Do you believe we should let two peoples of Europe (Britain and Russia) seize this giant inheritance with impunity? Rather than suffer this, I will say to my country with energy, with conviction: Rather war!”

To be clear, I do not mean to suggest that liberalism intrinsically legitimates racism and authoritarian rule, or that it intrinsically disavows them. Liberalism is a deeply ambiguous discourse, which can be (and has been) interpreted in different ways. Indeed, proponents of liberalism have habitually made use of this ambiguity, which has allowed them to strategically promote or disavow racism and authoritarianism depending on the circumstances. This behaviour is criticised in a famous 1883 text by James Fitzjames Stephen, a prominent liberal and former high imperial official in British India. In the text, Stephen criticises other liberals for failing to honestly acknowledge the character of liberal imperialism. Like Stephen himself, these other liberals wish to retain a racist authoritarian regime in India. Nevertheless, unlike Stephen, they are not willing to admit this fact. Stephen writes, “(The British imperial regime in India) is essentially an absolute Government, founded, not on consent, but on conquest. It does not represent the Native principles of life or of government, and it can never do so until it represents heathenism and barbarism. It represents a belligerent civilisation, and no anomaly can be so striking or so dangerous as its administration by men who, being at the head of a Government founded upon conquest, implying at every point the superiority of the conquering race, of their ideas, their institutions, their opinions and their principles, and having no justification for its existence except that superiority, shrink from the open, uncompromising, straightforward assertion of it, seek to apologise for their own position, and refuse, from whatever cause, to uphold and support it.”

Syed Ahmed Khan didn’t allow beef in Aligarh College

Stephen’s views were echoed by countless others during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Nevertheless, discourse of this kind developed variations across nations. In this respect, it is useful to contrast British and French discourses on liberal imperialism. French writers pointed out that the British actually endorsed two types of imperial policy. In lands that the British wished to settle, they simply exterminated the indigenous population (e.g., Amerindians in North America and aborigines in Australia). In lands that they did not wish to settle (like India, Malaya and Nigeria), they established racist authoritarian regimes. Criticising the British (and, by extension, the Americans, Canadians and Australians) for their brutality, the French rejected the practice of extermination, even in lands they were settling (e.g, Algeria).

Arthur Girault (1865-1931) was a French law professor best known for his 1895 treatise on liberal imperialism: Principes de colonisation et de législation colonial (Principles of Colonisation and Colonial Legislation). Girault’s ideas, along with those of Leroy-Beaulieu, shaped French imperial policy vis-à-vis its sizable Muslim populations. In Principes, Girault draws on the social-Darwinist ideas of leading British liberal intellectual Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), famous for his expression “Survival of the Fittest”, which led Spencer to endorse eugenic “restriction(s) on the multiplication of the inferior”, believing that the progress of civilisation and human happiness go hand-in-hand with the destruction of biologically inferior populations.

Other contemporary thinkers draw on this line of thinking to argue that mass rape accompanying military conquest is a net benefit as it spreads the genes of the superior conquering race.

Girault then considers how the French empire can apply his ideas to Algerian Muslims. Hence, should Algerians be exterminated or should the French take a different approach? Girault writes that one option is to “destroy the indigenous (Algerians) or at least drive them away”. One could think of that in the past, when it was believed the indigenous population, like the redskins or the Australian aborigines, would disappear by melting upon contact with the Europeans. But the idea was quickly abandoned as the “natural generosity of the French race” immediately protested against a monstrous policy of systematic destruction. “A war of extermination would have raised against us not only the natives of Algeria, but the entire Muslim world. Driving them away (refoulement) is no less impractical, because pastoral people need a lot of space, and the tribe that spends the winter in the Sahara must return during the summer to lead its flocks into the pastures of the Tell.”

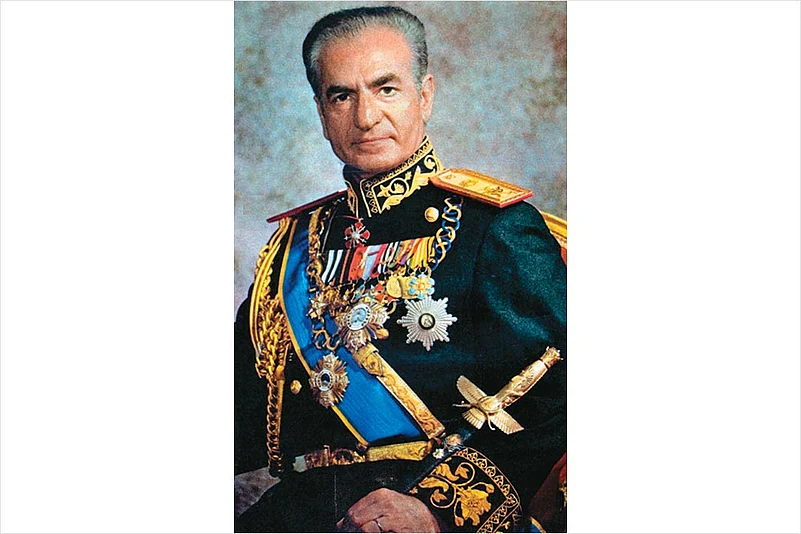

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran

Girault’s approach to this issue indicates the factors relevant to formulating a distinctive imperial Muslim policy. He notes that unlike Amerindians and Australian aborgines, Muslim populations will not simply disappear upon contact with Europeans, hence Europeans must find a way to deal with them. Simple wars of extermination are not appropriate as such a policy conflicts with the “natural generosity of the French race” (which marks its moral superiority over the British) and Muslims across the world are likely to engage in violent retaliation. While it may be possible to exterminate a tribe of Ameridians or aborgines, Muslims have a transnational identity that makes them likely to support and protect one another. As we will see, a central aim of imperial Muslim policy is to destroy this transnational identity.

“Once we have condoned the great violence that is conquest, I believe that we must not shrink from the smaller violences that are absolutely necessary to consolidate it,” writes Tocqueville (1846). Just as liberals used extreme violence and torture to force Muslims to adopt western civilisation, the same tactics are used by dictators throughout the Middle East which are backed by the West today. A good past example is the Shah of Iran, who ran SAVAK, secret police of the Pahlavi dynasty, with US cooperation. A senior SAVAK officer later wrote that after Siahkal interrogators were sent abroad for ‘scientific’ training to prevent unwanted deaths from ‘brute force’, “brute force was supplemented with the bastinado; sleep deprivation; extensive solitary confinement; glaring searchlights; standing in one place for hours on end; nail extractions; snakes (favoured for use with women); electrical shocks with cattle prods, often into the rectum; cigarette burns; sitting on hot grills; acid dripped into nostrils; near-drownings; mock executions; and an electric chair with a large metal mask to muffle screams while amplifying them for the victim. This latter contraption was dubbed the Apollo—an allusion to the American space capsules. Prisoners were also humiliated by being raped, urinated on and forced to stand naked.”

“Here, I believe, we are touching on the cause of one of the most serious problems of our times, and this problem affects all but the most ‘privileged’ countries: to evolve, or not to evolve?” he writes. “Patiently to remain members of the Third World, or to try to cross the threshold beyond which lies modern civilisation? When I began to implement a shock programme that would allow Iran, in 25 years, to catch up on a delay of several centuries, I realised its success would only be possible if all the forces of the country were mobilised. It was, I repeat, a permanent ‘state of emergency’ that had to be resorted to if one wanted to prevent the hostile elements from hindering it: reactionaries, great landowners, communists, conservatives, international intrigues. To ‘mobilise’ a country, it must be trained, pushed, pulled and, while it gets to work, defend it against those who would impede it. In this case, we had to choose. But choose what? Not, as it is abusively claimed, between the forceful method of ‘tyranny’ and the humanitarian principles; it was necessary to choose between sterile agitation, demagogic claims and the true interests of the Fatherland.”

In other words, the Shah, like Abdelaziz Bouteflika, Abdul Fattah Al-Sisi and Muhammad bin Salman, used dictatorial means to coerce the adoption of western civilisation with backing from the West. That is what causes violence.

M.J. Warsi is a linguist, author and columnist based in AMU