Angélica Dass is an award-winning Hispanic-Brazilian photographer whose practice combines photography with sociological research and public participation in the defense of human rights worldwide. She is the creator of the acclaimed Humanæ Project, a collection of portraits-in-progress that reveal the diversity in the beauty of human skin colour and stands as an extraordinary global anti-racist testimony.

Dass’ work has been shown at the World Economic Forum (Davos), UN Habitat III, the Montreal Fine Arts Museum, The Hague Museum, the Musée de l'Élysée in Lausanne, National Museum of Ethiopia, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, the Dublin Science Gallery, PhotoEspaña, American Museum of Natural History in New York, Fotografiska; in the streets and museums of Madrid, Bilbao, Chiasso, Zagreb, Milan, Thessaloniki, São Paulo, Mexico City, Austria, Santiago de Chile, Pittsburg, Kingsport, Seoul, and other cities; in National Geographic, Foreign Affairs, and on the BBC, among others.

Excerpts from a chat with Dass:

One particular skin colour—White—is considered the ideal of beauty, in many places across the world, including India. Do you wonder why this became the beauty standard for women?

It is part of a cruel dynamic. White is not a skin colour, whiteness is a social construct. Ancient Greek statues are often assumed to represent idealised white, 'natural' beauty. This is a projection of modern biases. Scientific advances reveal its original appearance: a woman with an olive or light brown complexion and heavily made-up, her hair possibly Afro-textured.

The idea that light skin is more beautiful than dark skin is the consequence of colonisation and racist Western beauty norms in many contexts. Mainly, preferences for light skin have their roots in Western colonisation. We have to acknowledge how categorisations of racialised beauty have been a tool of colonial violence. Humanae rejects a singular understanding of race through skin colour, and highlight how whiteness is also manifested in the pursuit of beauty in relation to facial features. Colonialism has often used the idea of beauty to disguise racial fetishisation, scientific racism and ethnographic profiling.

You've photographed many people from different places and backgrounds. Beauty is subjective, isn't it? And yet, women are judged by their looks and pressurised to look youthful.

Beauty is a social construct that functions in a dynamic of comparison with "the other". This search throughout our history tries to reach an ideal that is impossible, and women mostly suffer from this pressure. To grow old becomes a process of deterioration and to be beautiful is to try to reach the impossible. The objective of my work is to generate conversations where we can celebrate that we all have beauty.

Do you think the advertising industry and other visual media create impossible beauty standards for women (through airbrushing, make-up, etc) and make women chase after models of physical perfection?

Definitely, the visual language in different media is part of the creation of an imaginary about what is beautiful, ugly, good or bad, and social media with filter add a new layer in this process, but I want to be optimistic. Until recently, non-white women—particularly those

with darker complexions— were almost invisible in mainstream popular culture. Those who did appear were generally women seen as conforming more closely to Eurocentric beauty standards. But a long overdue increase in darker skinned women can now be seen on our screens and magazines. Their presence, as well as the broad range of characters they play, suggests things are finally starting to change.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

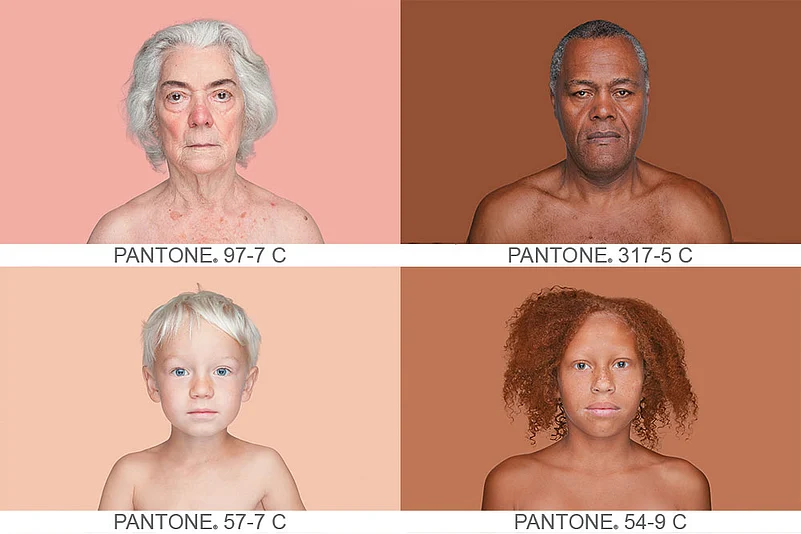

About the Humanæ Project

Humanæ is a photographic work-in-progress by Angélica Dass, an unusually direct reflection on skin colour, attempting to document humanity’s true colours rather than the untrue labels “white”, “red”, “black” and “yellow” associated with race. It’s a project in constant evolution seeking to demonstrate that what defines the human being is its inescapable uniqueness and, therefore, its diversity. The background for each portrait is tinted with a colour tone identical to a sample of 11 x 11 pixels taken from the nose of the subject and matched with the industrial palette Pantone®, it calls into question the contradictions and stereotypes related to the race issue. The direct and personal dialogue with the public and the absolute spontaneity of participation are fundamental values of the project and connote them with a strong vein of activism. The project does not select participants and there is no date set for its completion. It features someone included in the Forbes list, to refugees who crossed the Mediterranean Sea by boat, to students both in Switzerland and the favelas in Rio de Janeiro, people at the UNESCO Headquarters, and at a shelter. A variety of beliefs, gender identities, physical impairments; a new-born, or terminally ill people; all together build Humanae.

Currently, more than 4,000 images exist in the project. They have been taken in 37 cities, in 20 different countries: Arteixo, Madrid, Barcelona, Getxo, Bilbao and Valencia (Spain), Paris (France), Bergen (Norway), Winterthur, Chiasso (Switzerland), Groningen, The Hague (Netherlands), Dublin (Ireland), London (UK), Tyumen (Russia), Gibellina and Vita (Italy), Vancouver, Montreal (Canada), New York, San Francisco, Gambier, Pittsburgh and Chicago (USA), Quito (Ecuador), Valparaíso (Chile), Sao Paulo, Brasilia and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Córdoba (Argentina), New Delhi (India), Daegu (South Korea) Wenzhou and Shanghai (China), Ciudad de México, Oaxaca (Mexico) and Addis Ababa (Ethiopia

(This appeared in the print as 'Beauty Is A Social Construct')