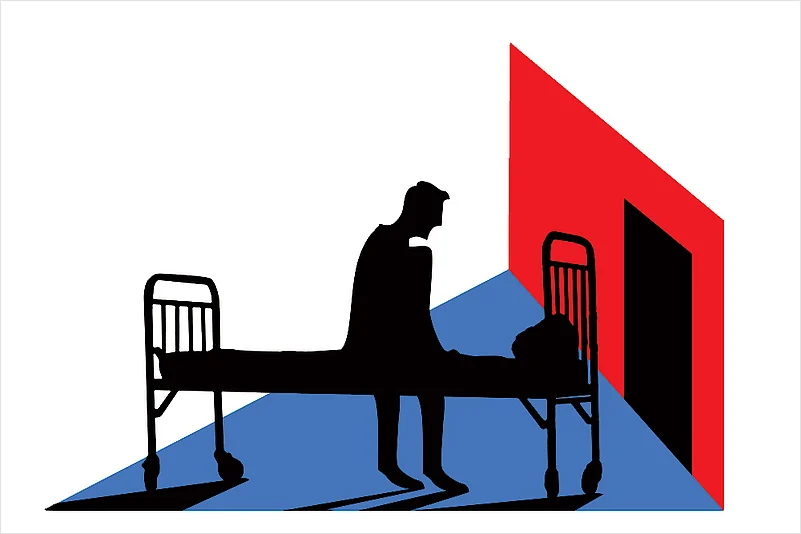

Back in the late 1980s, the acronym still freshly evoked that strange, intense fear of the unknown—a biological version of xenophobia. And the knee-jerk response: banishment, ostracism, or their medical variants. It was as good as incarceration for the man they called ‘Goa’s Patient Zero’. This May, we mark 25 years since Dominic D’Souza died. Sadly, we cannot say the stigmatisation brought on by the letters AIDS and HIV has ended. Dominic’s battle against prejudice, discrimination and ostracism of patients in Indian society has not yet been won. Far from it. Just recently, an acquaintance of mine reached out to me seeking help. He had been diagnosed as HIV-positive. He managed somehow to keep it under wraps for a bit but when it was no longer possible to hide it, the discrimination started at his workplace. They didn’t fire him but they made it so difficult for him to survive that he finally resigned. I don’t want to reveal his identity but he’s a creative artist…very sensitive and totally shattered by what’s happened. He desperately needed counselling. That’s the way the cookie crumbles still.

It’s so stark you can’t miss it. Patients of other terminal illnesses, like cancer, receive a natural compassion from society. In the case of those diagnosed with AIDs, there is only repulsion. As if the physical pain and the mental anguish of imminent death are not enough. I often wondered how two diseases produced such radically opposite reactions, even though each is equally serious. The penny dropped with an analogy: who are the only other victims who, paradoxically, find themselves at the receiving end of prejudice? Victims of rape, of course. I realised the answer lay in our society’s deeply conflicted perceptions of sex. Repressed desire at the personal end, turned to a cultivated disdain and stigma at the social level. Being infected with the HIV virus is an indication of sexual transgression. Perversely, so is rape often read as such. So the victim becomes the outcast.

Of course, there’s one area where positive changes have indeed taken place. When D’Souza was battling prejudice in the late ’80s and early ’90s—after being quarantined in a tuberculosis ward for 64 days with an HIV diagnosis—there were few laws to protect him against such injustice. Over the years, however, that lacuna has been partly filled. Last month, Parliament passed the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) Prevention and Control Bill, 2017—so we at least have a legal promise that equal rights will be ensured for those infected with AIDS and HIV. It criminalises various forms of discrimination and permits sufferers the right to confidentiality. To quote from the Bill, it prohibits “denial, termination, discontinuation or unfair treatment with regard to employment, education establishments, healthcare services, residing or renting property or standing for public or private office”. Such legal support is very important, even if not sufficient. As we have seen in the case of my acquaintance who faced it recently, unless the stigma itself goes, society will find ways of working through the loopholes. (In his case, they couldn’t legally terminate his employment but they socially boycotted him).