In that November of 2008, Barack Obama had broken the highest glass ceiling in America to become the first ‘black’ man to enter the White House. Young, handsome, cerebral, with exemplary oratorical skills, an inspirational life story and audacious electoral campaign. He had caught the imagination of US voters. More than that, the campaign seemed to connect America directly to the world at some level. After a long time, there had appeared the vision of a US president who was truly a citizen of the world, one who wanted to make peace, not one blinkered by partisan national goals. It didn’t take long for the sheen to peel off the man. And four years on, what we see is not merely a diminution, but at least on the world stage, almost an inversion into what you’d have thought a polar opposite.

So, as he sets out in his quest for a second term, it’s with an alarming drop in his popularity ratings, leading many to ask: how big of an underachiever is Barack Obama? The world is reeling under a global economic crisis, but instead of creative ideation one sees him lapsing into protectionist rhetoric. The entire Arab world is in the throes of a political upheaval, but he is a cautious onlooker. For a man who promised to bring a pacifist turn in world affairs, Obama has neither been able to make peace with the Arab world, nor keep Israel complaisant. Hardly the effect one would expect a statesman to have.

Back home, Obama’s detractors in the Republican Party are labelling him as a “softie” and an “apologist”, trying to apologise to the world for the policies of his predecessors. But many of his erstwhile supporters and admirers are also disappointed at the opposite: with the compromises he is making, often by diluting his own policies and at the cost of ignoring many of his electoral promises—whether to shut down the Guantanamo Bay prison, where over 170 Al Qaeda prisoners are being held, or his vow to deal with the Arab world as “equals” or his claim to encourage a fairer and just world.

He also angered his European allies by trying to spread the blame of the recession across the Atlantic, perhaps under pressure from Republicans and political detractors. The Europeans feel that instead of doing some serious introspection at home—since the economic crisis was kickstarted in the US—Obama was now coolly trying to pass the buck to Europe.

While his domestic ratings have been hovering in the 40s—which his campaign managers justify as being natural for an incumbent president—it is the significant fall in his ratings in the outside world that comes as a surprise to many. The latest survey, conducted by the American Arab Institute (aai) in five countries in the Arab world, shows Obama’s ratings to be as low as that of his Republican predecessor, George W. Bush. “Though he did not create the problems,” says aai president James Zogby, “he created the expectations that they can be solved.” Zogby attributes the drop in Obama’s popularity ratings largely to his inability to deliver on his promises.

Obama had indeed kindled much hope with his much-celebrated June 2009 speech in Cairo. Quoting passages from the Quran, he had embarked on his first major mission to heal Arab wounds by stressing that Islam was a religion of peace and had no inherent clash with the West. In an attempt to reinvent America’s standing in the world and reach out to countries—friends and foes alike—via dialogue and engagement, he had tried to convey the clear message that outstanding differences would be settled through dialogue, not war. The US president spoke like a sensitive man of the world, one well aware that the war on terror unleashed by Bush post-9/11, an extension of which saw US troops in Iraq, had alienated a large number of people in the Arab world.

Obama also had a clear-eyed sense that the root of the problem lay in the unresolved dispute between Israel and Palestine. And that as long as it remained unattended, the mistrust between the US and much of the Arab world would continue to fester. As such, he had promised to restart the stalled peace process in West Asia by bringing an end to Israeli settlements in Palestinian areas. However, despite the initial brave words, Obama chickened out of implementing his promise in the face of strong opposition from the Israeli government and their strong and influential Jewish backers in the US.

“The Middle East peace process was Obama’s biggest foreign policy failure,” Shlomo Ben-Ami, Israel’s former foreign minister, told Outlook. He categorises Obama’s attempt to put a freeze on the settlements as a precursor to the revival of the peace process as a tactical mistake since it hardened the position of Israeli leaders. He appointed George Mitchell as his special envoy to West Asia, but the lack of any forward movement soon forced the senator to resign. “The US president talked the talk but didn’t walk the walk,” says Ben-Ami. This failure, he argues, allowed Benjamin Netanyahu to divert the focus from the Palestinian issue to Iran’s nuclear programme.

Even here, Obama retreated from a promising start—the idea of direct talks died in the post-natal ward, under pressure from the Jewish lobby in the US and Israel. From allowing limited uranium enrichment, he hardened to the position of no enrichment, while imposing more and more sanctions on Tehran. According to Trita Parsi, a Washington-based expert on Iranian affairs and author of a book on Obama’s Iran policy, though the American president came armed with a fresh approach on Iran, he had limited political space and wanted to show results fast, something difficult to achieve in relations as complex as those between Washington and Tehran. Even the latest round of talks with Iran in Moscow failed, because Obama was balancing conflicting interests and pressures in an election year. “Even a small deal in Moscow was not pursued in the belief that it would be politically too costly at home,” says Parsi.

One could well argue that the Obama we see today is a man awakened to realities, a man who has realised that it is easy to promise dreams, tougher to build them. However, Obama is the president not only of the world’s oldest democracy but also of the sole superpower of the world. And he happens to be at the helm during the worst global economic crisis in recent memory—a time when a proactive leadership of ideas was called for. What everyone got was a string of compromises with political opponents and a trail of debris of broken campaign promises.

Not many are willing to forgive Obama that easily, or allow circumstances to attenuate his blame. They had reposed far too much faith and confidence in his ability to heal the world by establishing the principles of freedom, liberty and justice. And when change did come, with the Arab Spring, Obama was found dragging his feet, his delayed response disappointing people in this part of the world who expected him to be a ready ally in the toppling of autocratic regimes. Perhaps he was trying to rebalance his position with various factions in the US. But as former Indian diplomat Talmiz Ahmed comments, “If Obama had pursued his conscience, he would have robustly supported the Arab people’s aspiration for freedom and liberty. Instead, he was trying to push an agenda to ensure America’s hegemony in the region against people’s aspirations.” “It is most disappointing,” Ahmed goes on to add, “that Obama’s policies turned out to be no different from those of his predecessors.” Everyone agrees that Obama failed to follow his words with commensurate action in the Arab world. But what of India, the land of Mahatma Gandhi, whose portrait hangs in his Senate office and whose words—‘Be the Change’—became the rallying cry on his inaugural poster? How should we see Obama’s policies?

Laden moment From a policy of least involvement, US has moved to attacking enemy positions in Af-Pak region

The US president has come a long way from the days when he laid out his Asia Security Strategy and forgot to mention India. The US has now come to recognise India as the “lynchpin” of its security policy in the region, never mind if it came after Beijing rebuffed his attempt to set up a Group of Two (G-2) arrangement. However, Indian policy planners and commentators are not losing any sleep over hiccups that might have been. As long as India’s core concerns, namely over China, Pakistan, Kashmir and in the nuclear field, are taken care of, and as long as the US is not planning a special arrangement with China to run Asia’s security, New Delhi has no reason to complain. “Obama turned out to be far more supportive of India than initially expected,” says C. Rajamohan of the Observer Research Foundation. Why, from a stance favouring minimal involvement in Afghanistan—largely to keep Pakistan happy—to a position where US drones are not only constantly attacking terrorist positions on the Af-Pak border but it is also asking India to play a much larger role for the peace, stability and prosperity of Afghanistan, it is a significant shift in India’s favour. Not only that, Obama has also promised to support India’s candidature in the UN Security Council and field it in other important bodies like the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group and the Wassenaar Arrangement.

Is all of this an afterthought? Srinath Raghavan of the Centre for Policy Research strikes a sceptical note about America’s moves. “The US now wants India to play a more active role in ensuring a more balanced power structure in Asia. But it is not clear that India will cease to be influenced by tactical shifts in the US-China relationship,” he says.

Raghavan also expresses disappointment over America’s policy of trying to isolate Iran, which he feels will adversely impact the outcome of stability in Afghanistan. “Attempts to box in Iran will have serious implications for Afghanistan. It is surprising that the Obama administration is following this course, while simultaneously wanting to leave behind a stable Afghanistan,” he says.

So, in a tired status-quoist sort of way, if one considers national interest to be permanent and paramount in foreign policy, Indians would not be too unhappy were Obama to get a second term. At another level, though, it shares the disappointment with the world over the man who first taught the world to say ‘Yes, we can’ only to discover that, no, he cannot.

***

How Obama Is Tripping Vis-A-Vis India

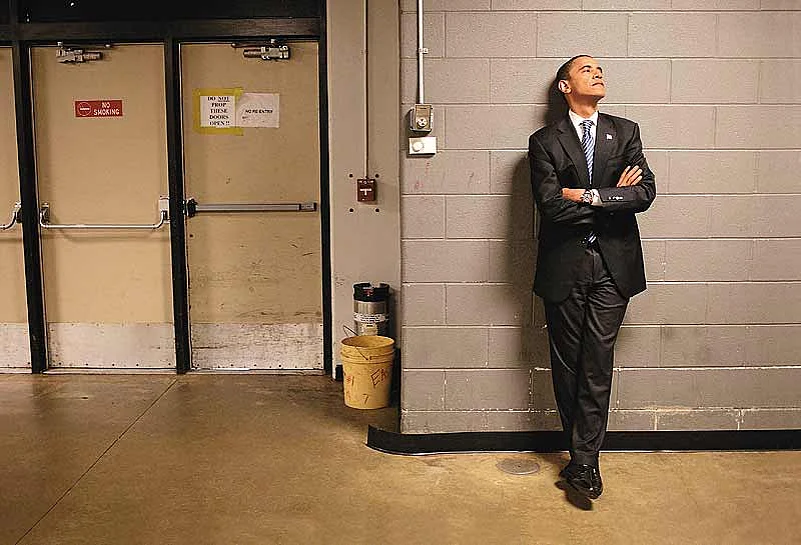

Photograph by Prabhjot Singh Gill

FDI Obama’s push for more foreign investment betrays an ignorance of India’s complex socio-economic and political reality

Iran America’s growing pressure on India on economic engagement with Iran ignores realpolitik and traditional ties

Photograph by Quickpix

Nuclear deal Touted as the touchpoint in Indo-US ties, Obama has not been able to work around liability laws