Literary critics, like feminist Nicole Ward Jouve, have argued that all autobiographical writing might be seen as fiction and even critical writing might be seen as autobiography because whether it is a memoir, short story, poetry, novel, or an essay, irrespective of genre, the individual author writing offers one perspective. Your version. It is your view, your understanding of memory, of what you remember and forget. There is no scope to offer an empirical or objective view of the world, you simply can’t. And, these critics argue, based on developments in literary theory in the last century, no writing can.

Autofiction goes further, and lets you paint new visual imageries of your truth. One does not start writing a memoir with the intention that it should become autofiction. The term was coined by literary critics from the West for a genre that, they claimed, emerged late in the 20th century.

Yet Black American autofiction began with slave narratives, memoirs and stories of emancipation, began in the 19th century and centred on historic events such as the American Civil War and the building of the Underground Railroad, which northern abolitionists helped publish to highlight the plight of the southern slaves.

While former slave turned abolitionist Frederick Douglass is the most recognised name from his autobiographies, the first one and the most iconic being Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), it was his influence over a black woman slave Harriet Jacob that indirectly made up for the paucity of women literary voices in the anti-slavery fight. Jacobs, as Linda Brent wrote (it was often White women who wrote these narratives as amanuensis and scribe as Blacks were denied literacy), wrote the first slave woman narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 1861, and through Brent, the world learned of Jacob’s story, the woman’s perspective in slavery, sexual abuse by white owners, mixed-race children, and that aiming for freedom and a good mother are two seemingly different goals. It encouraged other free black women such as Mary Prince, Mattie J. Jackson, and a nonagenarian, only known as “old Elizabeth” to chronicle their struggles through prose or oral narratives.

The genre of slave narratives ended gradually after President Abraham Lincoln abolished slavery, but even today, in the 21st century, after a black man has served two terms as President, the African American narratives, the #BlackLivesMatter movement continues to record the trenchant racism in US society and Black disenfranchisement. “The quality of ‘freedom’ or lack of it, always being agonised about. The Dalit position in our country on paper is equal but hardly equal,” notes Tapan Basu, retired professor from Delhi University’s English Department and a specialist in African-American literature. The fight against racism, says Basu, was for the longest time also “male-centric, and even downright misogynistic”. There was the assumption that only Black men had to bear the burden of fighting white power.”

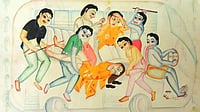

As in the case of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937, novelist Richard Wright, in a review, said, “Miss Hurston seems to have no desire whatsoever to move in the direction of serious fiction.” Now considered a Harlem Renaissance classic, Hurston’s novel is about Janie, whose mother and grandmother, both victims of rape and discrimination; marry her young to ensure a stable future. But she undergoes a string of failed marriages, each husband either controlling, using like as bait, or irresponsible, with the plot using metaphors like the sport of mule-baiting to symbolise the role of women. In the end, she is single, financially independent, and free from societal demands.

“Some of the Black men were sexiest, wanted the women to blindly follow their lead. It is why James Baldwin was not popular with these ‘macho’ Black male writers because he was gay,” adds Basu.

It was in the late 1950s and 60s that a revolution began, when black women such as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, Maya Angelou, all Baldwin’s friends, started writing furiously against two enemies: racial discrimination and Black masculinity. Writing was all they had, and their stories, personal and in fictive form, rooted in reality, threw up all kinds of adversities to inspire the Black sisterhood to power on.

“Earlier, those pursuing an MA in English Literature either just studied British writers or white American writers. One had a very colonial narrative of race, of whiteness, of Eurocentric supremacy, which came through the texts that were being taught. The syllabus with works of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Robert Frost never made space for the Black experience in the United States. But once Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Langston Hughes, and James Baldwin, entered mainstream academics and postcolonial writing, it changed the way US literature was read. One started looking at marginalised voices, and past the stereotypes that colonialism had given, and those who read Black American writing started to work on Dalit writings in India,” says Dr Mala Pandurang, Principal of BMN College of Home Science and a specialist in African and African-American writing.

Walker’s 1983 book of essays In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: Womanist Prose is iconic for its coinage of ‘womanist’, a term for Black American women struggles and a new kind of prose. A new edition of Walker’s Color Purple, her Pulitzer-winning novel, published recently in a new 40th-year edition, is about a girl, Celie, raped by her father, further abused by her husband, who falls for a woman (a stunning bisexual jazz singer loosely based on Billie Holiday), and finds love, her own body, her sister and a close clique in the end. In one of the most memorable scenes in the book, excised from Steven Spielberg’s film version, Shug Avery (the jazz singer) introduces Celie to her clitoris.

While Martin Luther King wrote Letter From Birmingham Jail on the margins of a newspaper, civil rights activist Maya Angelou wrote the first (and most popular) of her first autobiographical volumes titled, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, 1969, on yellow legal pads. Protagonist Maya is abandoned, and experiences racism, sexual assault by her mother’s boyfriend, and her self-doubt of being a lesbian but becomes pregnant. Angelou’s autobiography runs into seven volumes, all written in first person, following the slave narrative tradition, offering the narrative of a bold, non-conformist black woman, who took destiny into her own hands. These books trace her growing years, as a single mother, her first marriage to a white man, becoming a civil rights activist, and published author, years in Cairo and Ghana, return to America, coping with the assassinations of her friends Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., and lastly reconciling with her mother in the final title Mom & Me & Mom.

Audre Lorde, who married a gay white man, had two kids, divorced, brought out three anthologies on women’s writings, including a poem titled Martha which confirmed her orientation; got diagnosed with breast cancer and wrote The Cancer Journals (1980) to highlight how the treatment and care were centred on the white, heterosexual women, eliminating the wants of the African Americans and sexual minorities.

Her 1982 ’biomythography’, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, combines facts and myths, having Lorde open up about her childhood in Harlem to identify herself as a ‘black, lesbian, feminist socialist mother of two'. At other times, the references to the personal are subtle.

Toni Morrison, too, relied on she speaks of her collected works across four decades and says, “I suspect my dependency on memory as trustworthy ignition is more anxious than it is for most fiction writers – not because I write (or want to) autobiographically, but because I am keenly aware of the fact that I write in a wholly racialised society that can and does hobble the imagination.”

Morrison’s first novel The Bluest Eye is set in Ohio, Morrison’s hometown, where a black girl, Pecola, yearns to look like a white girl.. Home sees a black war veteran caught in a racial struggle on his return from the Korean War. Tar Baby sees a black love story between a fugitive and a top model.

There’s also Lorraine Hansberry, the first black woman to produce a play on Broadway. Her A Raisin in the Sun, is subtly autobiographical, based on a childhood experience of moving to a white Chicago neighbourhood that retaliated till her family got evicted, a narrative much like the Younger family in her play. Her actual autobiography, stitched together posthumously by her ex-husband into a play To Be Young, Gifted, and Black, and then became an ‘informal autobiography’.

Ever since African American or Black women’s writing burst onto the scene in the 70s, accompanied by a strong second-wave feminist movement, Black women have not looked back. Whether it is an autobiography or autofiction (and, as we have seen, the lines between these are blurred), Black women have re-defined their experiences and their lives through the act of writing.

Young Black women writers learn from these foremothers. If Alice Walker could find no writing by her foremothers (and had to find gardens and quilts) instead as she showed us in her extraordinary essay In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens, she and a range of other writers like Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, Lorraine Hansberry and Maya Angelou have ensured that young Black women will never fall short of writer foremothers ever again.