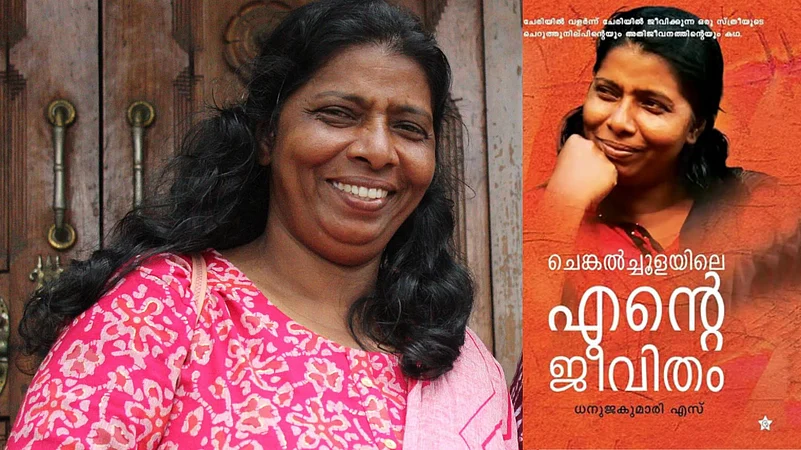

While Dhanujakumari, the sanitation worker from Chengalchoola, the "most notorious slum" in Kerala, writes her autobiography, it becomes the cultural and political history of the slum itself. Though Dhanuja Kumari is a school dropout, her autobiography My Life in Chengalchoola has been included in the elective course on Biographies for the MA and BA Malayalam students at two universities in Kerala. While writing the book, Dhanuja Kumari never expected such a groundbreaking reception for her book, she says. What she wanted the world to know and understand the life of people in Chengalchoola and to stop stereotyping and humiliating . “There are artists, technicians, engineers, and even IAS aspirants from Chengalchoola. It is not all about crimes and drugs as society perceives,” says Dhanujakumari, who proudly asserts her identity as a slum dweller.

Apart from talking about herself, Dhanujakumari’s book is an attempt to change the wrong perception of ‘notoriety’ imposed on Chengalchoola, the slum located on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram town. Once upon a time, this slum was known as the hub of ‘criminals and drug peddlers.’ The youngsters were shy to introduce themselves as hailing from this slum to the world outside, fearing the discrimination they faced. In the book, Dhanujakumari narrates how even the auto drivers in the city refused to go to the slum and how the children had been discriminated against in school during her childhood, even at a time when she was too small to learn what discrimination is.

Dhanujakumari is a member of ‘Harita Karma Sena,’ the sanitation program run by the state under the local self-government. She is not a writer who had a room of her own. She lived in many houses in many places—even in an orphanage, as her parents could not manage the family in abject poverty. Despite being gripped by poverty, Dhanujakumari has fond memories of her childhood. She recalls the large group of children in the slum who played and lived together. The estranged relationship between her parents often resulted in interruptions to her studies. Little Dhanuja had to change schools several times. The children in Chengalchoola were not good at academics, she recollects, mostly because of the troubled relationships within families and the drinking habits of the elder male members. However, she fondly and proudly remembers how deeply secular Chengalchoola was. “We all lived together; interfaith/intercaste marriages were not unusual among us. There were five or more castes and religions even within one family,” she says.

She studied in a school in the heart of Thiruvananthapuram city in high school. Dhanuja recollects how indifferent the world was to the children from the slum. “We were ignored. Nobody cared for our existence. No matter whether we were good or bad in studies. Both had the same impact. No one cared,” she writes. Dhanuja was staying in an orphanage during high school. Her mother took her back home when she was in 8th grade. That was the end of her formal education.

Dhanuja fell in love and got married to a Chenda (a percussion instrument) artist, Sathish, soon after leaving high school. However, life since marriage did not bring any good change but only moved from bad to worse. Her husband Satish was a drunkard, which made her life hell. He used to go for performances and come back home with an empty wallet. Dhanuja even tried to die by suicide a couple of times. However, her determination to fight the struggles brought her back.

Dhanuja learned that a life quite ordinary would not help her make any meaningful change. Thus she took a life-changing decision to do something extraordinary. Though her husband Satish had given her nothing but pain and disappointment, she always admired and loved his talent as a percussionist. She decided to organize a performance that would be extraordinary and remembered by the world. Thus, the family organized a 48-hour-long Chenda performance at Ayyankali Hall in the heart of Thiruvananthapuram city. She borrowed the money for booking the hall and arranged for a few people to attend the program. After a few hours since the program started, the hall was crowded. When the performance finished after 48 hours, Satish was in full media glare. But Dhanuja’s intention was not just to grab the attention of the local media. She wanted to create a ‘Guinness Book of World Records’ by making Satish the first percussion artist to perform continuously for 48 hours. However, apart from working hard and organizing, Dhanuja had no idea how to make it happen. Hence, the dream of a world record did not come true.

However, Dhanuja’s dreams were nothing short of world records. Realizing the artistic talent of her elder son Nidheesh, she sent him to Kalamandalam (the University for Performing Arts) at the age of 13. The tag of ‘a Dalit boy from Chengalchoola’ made his life miserable at Kalamandalam. Dhanuja alleges that a teacher hated him, and the boy was even beaten by senior students. Unable to bear the torture, he gave up Kalamandalam and went back home. However, Dhanuja has no regrets. She thinks that it was the right decision. Nidheesh later joined A R Rahman’s Music School, K M Music Conservatory in Chennai, and successfully completed a course in music direction. The younger son Sudheesh also wants to follow his brother’s path—to join A R Rahman’s Institute and build a career in music.

Dhanuja’s dreams are never-ending. She wants to build a website on Chengalchoola, a space to record the cultural and developmental activities happening there. She wants to rebuild the image of Chengalchoola to change it from being known as a hub of drug peddlers and criminals to one of artists, engineers, actors, and civil servants. Dhanuja also wants to set up a library for the people of Chengalchoola. “We need 1,000 books and a building to get the recognition of the State Library Council. We are working towards materializing this dream,” she says.

Dhanuja’s autobiography ends with a note of hope. What she wants to achieve from her book is to change people’s perceptions. “I don’t expect a revolution to happen. The world outside this slum has to acknowledge that we also are human beings. We also deserve to be treated respectfully.”