- Agricultural growth has doubled since 2004. Rise in food production has boosted rural incomes, helped government keep prices under control.

- A sharp 30-40% increase in the minimum support price for cereals and the Rs 70,000 cr loan waiver have made agriculture more attractive.

- Growing industry demand for land has seen prices spiral even in rural areas, bringing overnight wealth to many villages.

- Rural people are taking up jobs in cities, leading to a big rise in remittances to villages.

- Growth of small enterprises created alternate income sources for most rural families.

- NREGS has created some additional income wherever it has been implemented properly.

- Hit by slow urban demand, companies shifting focus to capture the growth in rural markets.

***

Just how legitimate is the UPA’s claim of rural prosperity? Is the edifice of rural growth sound enough to withstand a slowdown in urban India? Or is it just driven by the marketing campaigns of corporate India seeking to expand out of the shrinking sales graphs in urban areas? Finally, does development really matter to the Indian voter; will they reward the incumbent alliance, the state government, or the opposition?

To find out, Outlook’s correspondents journeyed around seven key states, from the rural heartlands to areas afflicted by farmer suicides. They found a mixed picture of well-being and despair. Government subsidies, doles and the UPA’s 100-day guaranteed employment programme (NREGS) have definitely made a difference from an earlier hand-to-mouth existence. In many cases, urban hunger for land has helped transform lives overnight as farmland prices have soared, particularly close to cities, highways and planned industrial belts.

On the other hand, even for all the signs of prosperity, it’s not across the board. Most agricultural economists disagree with the "hype", and warn against generalising, while also insisting that there’s substance to the rural story. S.S. Acharya of the National Academy of Agricultural Science, feels "there has been a turnaround due to government policies" and that "the farmer’s faith in agriculture has been restored". There’s no denying that higher minimum support price (MSP) from 2005 and a step up in public spending on agriculture—along with the favourable weather of course—have helped double farm growth to around three per cent. "Four consecutive years of good agriculture growth has improved incomes to a great extent," says the NCAER’s Rajesh K. Shukla.

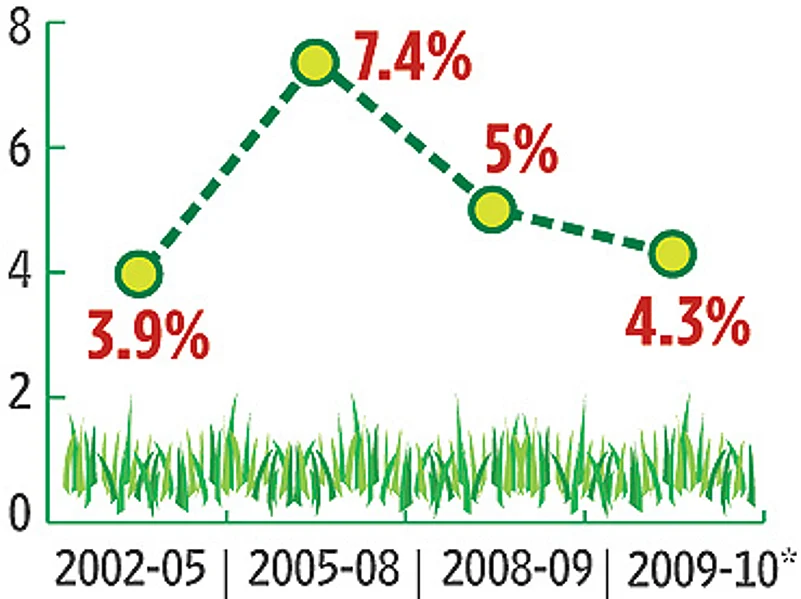

Real Rural GDP Growth

The rural growth and well-being being witnessed now are the early gains from the increased investment in the farm sector for crop diversification and creating alternate revenue channels from horticulture, poultry, fisheries and so on. In turn, success in these areas has given rise to many SMES in the unorganised sector. "Farmer suicides isn’t the whole story. The rural economy is growing at a much higher rate than the agriculture GDP," stresses agronomist Ramesh Chand.

The anticipation of another good crop year and further government initiatives are expected to help rural areas remain vibrant even during the present economic slowdown. "To think there will be a further upsurge in farm growth is wrong, but Indian agriculture and the rural economy have been holding out against the slowdown," says IRMA chairman Dr Yoginder K. Alagh. Ironically, behind this optimism lies the reducing contribution of agriculture to the total rural income. From less than 50 per cent now, Shukla expects the dependence of rural families on agriculture to dip to 37 per cent in the next five years. In fact, the growing services economy in the hinterland has played a big role in increasing rural well-being.

On the flip side, there are fears that just like after the 1997 Asian crisis, prices of agriculture products could collapse. Together with a prolonged urban slowdown, it could lead to further retrenchment of workers on whom the rural economy relies for remittances. "You will have to watch out for the secondary effects of a slowdown in rural areas," warns Pronab Sen, secretary, ministry of statistics, pointing to the huge return migration from Surat and Kutch, where many gold and diamond workers have lost their jobs.

As the reverse migration to rural areas gathers momentum, there are fears that skilled workers in particular may find it difficult to take up suitable alternate employment. Going by data, already the number of marginal workers is increasing while those with full-time jobs are decreasing. "Marginal employment is down from four days of work a week to 2.5 days a week," stresses sociologist Dipankar Gupta of JNU.

While the urban slowdown is hitting demand, the NREGS "has raised the purchasing power of rural consumers", feels Mihir Shah, co-founder of the National Consortium of Civil Society Organisations. That’s evident from the zooming sales reports of major companies for mobiles, televisions, DVD players or cars. Take the experience of DCM Shriram Consolidated’s Hariyali Kisan Bazaar at Sambal, a small town near Moradabad district of Uttar Pradesh. Last week, there was an unprecedented rush at the launch of a ‘summer collection’ of consumer products. The gates of the village store had to be closed thrice to manage the crowd.

But socio-economists find the trend disquieting. "It is a mirage of prosperity. Consumers are cutting down on necessities," says R.S. Deshpande, director of the Institute for Social and Economic Change. Indeed, he fears that the farm loans may have been diverted to buy the trappings of status. "Rural prosperity is restricted to a few places where high real estate prices have put money in a few hands," argues Krishan Bir Chaudhary of the Bharat Krishak Samaj.

There’s no denying that rural India is better off than five years ago. Whether all this will translate into positive votes for the ruling alliance is anyone’s guess. Outlook’s field reports indicate that rural voters aren’t very clear when it comes to giving credit for development—the state or the central government. The usual caste/religion politics appears to dominate. Not to be overlooked, though, is the desire for change—rural India is once again in a position to swing the vote against an incumbent government, irrespective of how well it thinks it has performed. Will rural voters buck the trend?

By Lola Nayar with Arindam Mukherjee and Pragya Singh