- Overflowing granaries in northern India as political compulsions lead to higher procurement

- Private traders largely staying away due to high minimum support prices

- Government to lift ban on wheat exports, despite global prices falling to unviable levels

- No word yet on subsidy to exporters, experts agree timing of exports is wrong

- Overstretched storage facilities deny hungry millions at home

***

In fact, there’s every indication that some action will take place before the new government takes office. Like in 2002—when India resorted to heavily subsidised exports to reduce stocks in overflowing granaries—the two-year-old ban on wheat exports will soon be lifted. "After May 16, you can expect the notification for allowing exports of up to two million tonnes," commerce secretary G.K. Pillai told Outlook. There’s no option, he argues. "The choice is between exporting or storing foodgrains in the open and facing spoilage or rats eating them as all godowns are almost full," says Pillai.

India’s problem of plenty has arisen not just due to the rise in domestic production, which increased by 32 million tonnes from the 2004-05 levels to reach a record 230.7 million tonnes in 2007-08. It’s also fuelled by the decision to create five million tonnes of strategic reserves—albeit by using expensive imported wheat. This has helped the government to keep the domestic wheat price in check even as all other food prices have been adding to inflationary pressures.

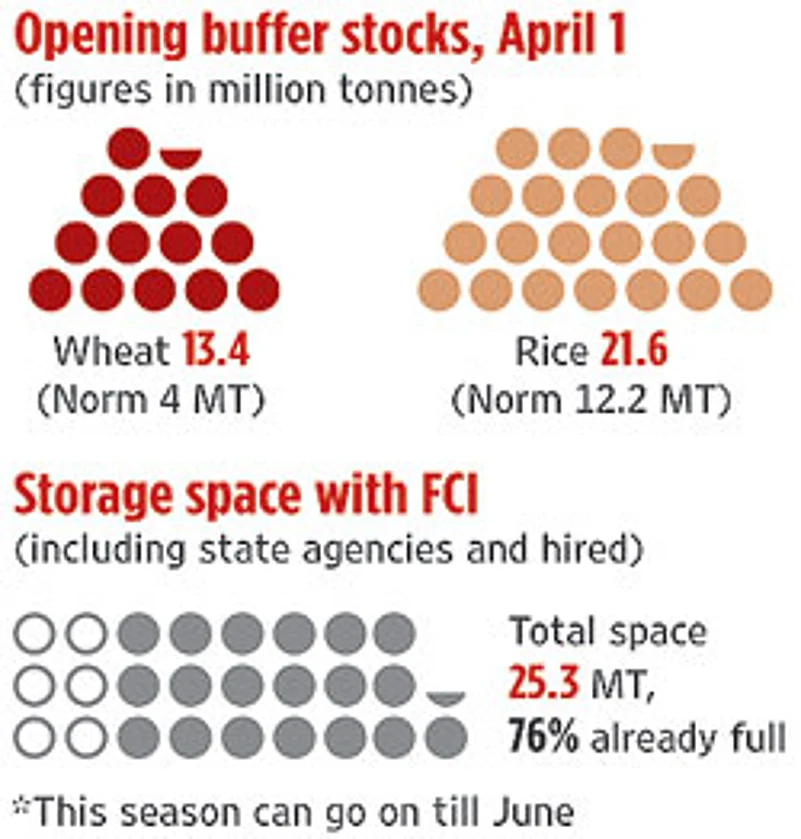

It’s true that government food stocks have not reached earlier peaks (70 million tonnes in 2002). But with 21.4 million tonnes of rice and 29.8 million tonnes of wheat procured as on April 30, state-run agencies—led by FCI—are finding it difficult to properly store fresh buys. FCI officials say 76 per cent of its 25.3 million tonnes storage capacity (including hired and those of other state agencies) is already filled.

The storage problem is acute in the wheat belt of north India. On March 31, the start of the fresh procurement season, Punjab had 9.77 million tonnes of foodgrain lying in its warehouses while Haryana had 2.4 million tonnes of last year’s stocks. With private traders staying away due to the high government-fixed minimum price ofRs 1,080 per quintal, the Punjab government was faced with a crisis in the middle of the election season. "Against last year’s procurement of 10.6 million tonnes, the arrivals in the first 40 days this year were 10.8 million tonnes," says D.S. Guru, principal secretary to the Punjab chief minister. But unlike the 3,00,000 tonnes bought by traders last year, this time just 19,000 tonnes were purchased.

Higher government purchases have meant creating additional storage space on a war footing by hiring godowns of rice sellers, and private open plinth storage and godowns. This is despite the Union food ministry moving some of the stored grain out of Punjab in special trains. What’s not helping matters is that farmers from Uttar Pradesh are also reported to be selling stocks in Punjab and Haryana. Given the domestic and global surplus situation, farmers do not seem keen to hold stocks this year, fearing a price crash.

To make up for lack of private sector participation, the FCI is targeting buying in excess of last year’s procurement. Even after accounting for the normal monthly offtake of about 3.9 million tonnes for various government programmes, the buffer stocks will be far in excess of last year’s stock. The way forward, agronomist Ashok Gulati of ifpri feels, is to allow "the private traders to hold stocks and export when world markets are conducive". But the government, he feels, never takes a timely decision. "The decision to export should have been taken long back when global prices were favourable and all indications of a bumper crop were evident."

Experts are critical of the ad hoc government approach from the early 1990s, which has contributed to the destabilisation of price and worked contrary to food security goals. Though public investment in agriculture has gone up in the last few years, not much has been targeted specifically at creating better storage, handling and distribution infrastructure. "India should not export foodgrain except speciality foods like Basmati rice, and use our food surplus for eradicating hunger. As recommended by the National Commission on Farmers, a universal public distribution system should be introduced," says Swaminathan, who headed the panel.

Given the election promises of political parties to provide more subsidised foodgrain, will the newly-elected government reserve the dole for the hungry millions instead of pushing out stocks via exports? That’s some food for thought for the new occupants at North Block.

By Lola Nayar with Chander Suta Dogra in Chandigarh