Why Things Are Looking Up

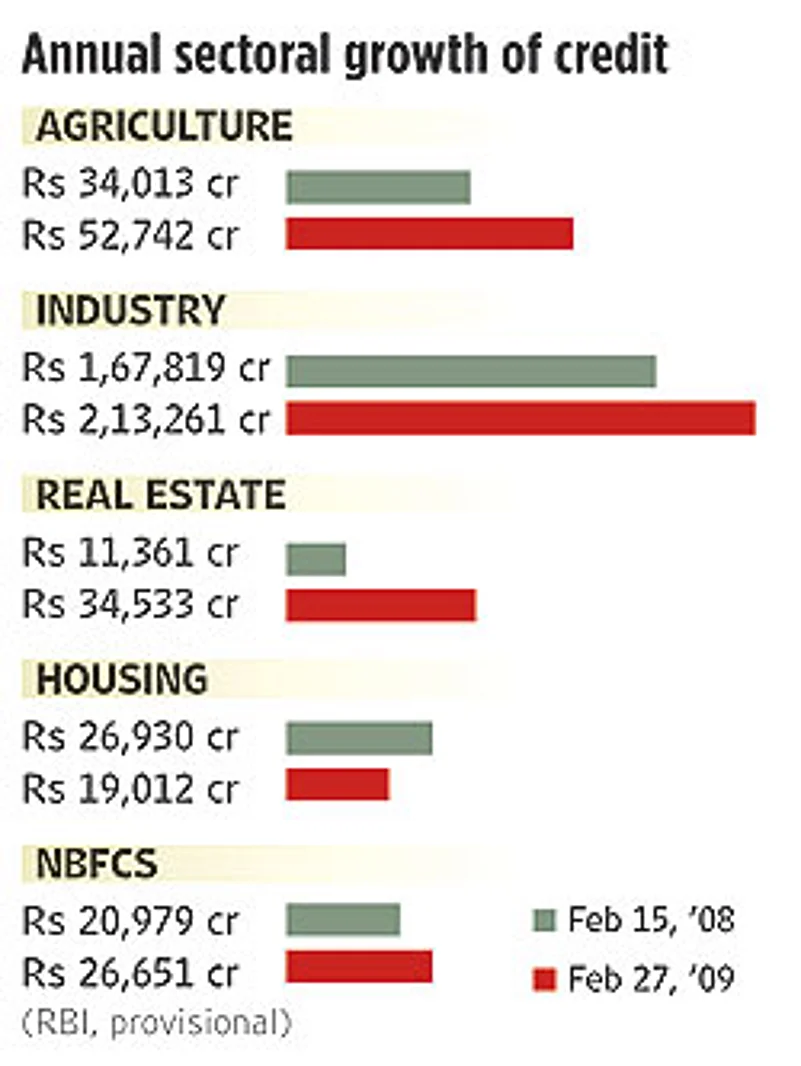

- Flow of credit is up, apart from housing where there are some signs of pick-up. Firms, consumers begin taking advantage of lower rates.

- Real estate deals are being sealed in urban pockets at today's easier price points; marginal pick-up in construction.

- Corporate results haven't been as bad as expected, but many sectors have poor expectations for the future.

- With huge buffer stocks, India does not face major problems in agriculture. Monsoon is also expected to be normal.

- On the back of improved global sentiment, FII inflows begin afresh in April 2009, pushing a swift stockmarket rally.

***

Why The Worry Lines Remain

- The RBI's latest forecast of real GDP growth for 2009-10 has been revised downwards to 5.7 per cent from 6 per cent.

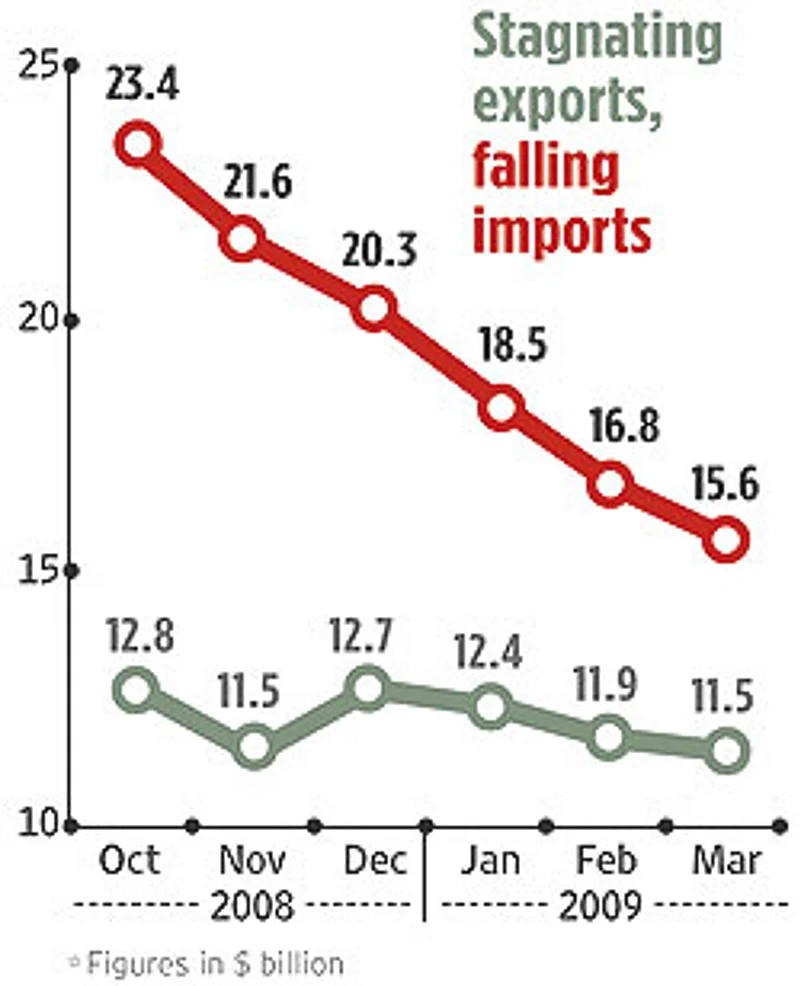

- For the first time, non-oil imports slowed down in January by 0.5 per cent. Non-oil imports make up a third of imports—a decline shows sluggishness in demand.

- Exports have shown a precipitous fall in recent months—overall growth is expected to be flat for 2009-10.

- Estimated at 5 lakh, job cuts are widespread, especially in the textile and jewellery segments. Also, widespread freeze on hiring for white-collar jobs.

- Public debt remains elevated at about 80 per cent of GDP—a very worrying sign for an economy that expects to thrive largely off government-supplied funds.

***

"Credit offtake today is working capital-related and not project-related, so I don’t see what the optimism is all about." Abheek Barua, HDFC Bank

"The government has dealt well with the fears of companies and people. We have had a good rabi crop too." Mahesh Vyas, CMIE

"I’m worried about the government giving money back to the people. It will lead to double-digit inflation." Parag Parikh, Stockbroker

"Things are better in terms of number of transactions, not prices. But the volumes are a sign of health." Pranay Vakil, Knight Frank India

"We are now slightly more optimistic but growth in 2009-10 will be 5-6% and 7.5-8% after 2010." Shankar Acharya, ICRIER

"It’s worrying if quarter after quarter brings bad news. So the recent stockmarket rally is a good sign." Shankar Sharma, First Global

***

Indians earned—and shopped to drop—through the 1990s and 2000s as a kind of backlash to all those earlier decades when imported goods were hard to come by and luxuries frowned upon. When last year’s downturn happened, many Indian consumers worried it was a backlash to their recent excesses. So, once again, they took the difficult decision to not buy, sell or invest for a while. But just as everybody settled into the new-old bargain routine, here comes the backlash to the backlash—we're suddenly talking upswing, upturn and even an imminent revival of the economy. Despite intermittent news over the last 10 months that the government and regulators have taken counter-measures to slowing demand, the instant reaction is sheer bewilderment.

So it's hardly surprising that our mythical Mr Kumar is somewhat confused. If things are indeed getting better, why is everyone taking salary cuts? After all, corporate India is ruthlessly—and in some cases cleverly—slashing jobs and increments. Then, if everyone is busy scrimping money to ride the tough times, who is pumping up the Sensex so we get that deja vu feeling, with TV images of people standing in front of the BSE building and smiling? Is this chorus of spring-like metaphors amidst continuing bad news just wishful thinking, a sense of relief that the heart-stopping days of the financial crisis are behind us?

Mahesh Vyas of the credit rating agency CMIE, which has long held a steady faith in the "fundamental" strengths of India's economy, says a measure of disquiet in the minds of consumers and industry is not out of place, though things really do look better than even just a month ago. "The extraordinary fear of both companies and consumers (over liquidity) has been dealt with reasonably by the government. We have had a good rabi crop too," he says, signalling that expectations of further improvement are not unrealistic. "The negative factor is that export-led industries are doing badly, due to which transportation and services are still feeling the pain."

If numbers don't lie, they are currently promising an improvement in the economy—capital that had pulled out is slowly trickling in again. The stockmarket has seen lively activity in April and May. Buoyed by the Pay Commission largesse, car-makers are still selling well and consumer durables are marching along nicely. Manufacturers are more upbeat than they were until January or February, when the index of industrial production (IIP) slumped into two all-time lows.

Having acknowledged that the days of easy credit are over, companies such as those in housing have quickly re-aligned prices. How far this effect will ripple on is anybody's guess, but Pranay Vakil, chairman of realty firm Knight Frank India, says the business is better today compared to October and November 2008. "Things are better in terms of number of transactions, not in terms of prices. But the volumes themselves show signs of a healthy market." What's heartening is that speculators and investors have exited the market "more or less".

Some of the good news portends a clear recovery from the downturn. The rest is pure logic, as Shankar Sharma of First Global explains: It's worrying for an economy if it sees only bad news quarter after quarter. So the recent rally in the stockmarket, for instance, is a positive sign. "However," warns Sharma, "we need more confirmation of the improvement because the scale of the problem is unprecedented. Also, India may still grow at a projected five, six or seven per cent, but that's not going to be good enough. It's way too early to say whether the current upswing will last or not," he cautions.

If you ask an economist, four major actors are at play in an economy: demand, supply, sentiments and macroeconomic factors. Of these, sentiment—the consumer or businessman's general cast of mind—has seen the greatest facelift. In a survey conducted in April 2009, ING, a global financial advisory group, found that Indian investors are the most optimistic in Asia. Then, ABN Amro recorded a seven-month high for Indian manufacturing units this month. On several fronts, including new orders and quantity of purchases, it also found significant improvement over the last few months. "The pace of deterioration has slowed and we seem headed for a phase of stabilisation," says Gaurav Kapur, senior economist, India, ABN Amro.

On other fronts in the macro economy, economists are still finding it hard to see growth at the coveted nine per cent rate until there is a full global recovery. This, they believe, could take two to three years. Shankar Acharya of the research firm ICRIER says we may have stabilised after seeing the worst of the slowdown in the last two quarters. "We are now slightly more optimistic but the full year growth in 2009-10 will be 5-6 per cent, and 7.5-8 per cent after 2010." The question here is: What will 5-6 per cent growth mean to India's burgeoning population of the jobless and new entrants to the workforce? In the last five months alone, more than 5 lakh jobs have been lost.

Also, the government's fiscal revival packages may have worked for now, but further stimulus may not be possible given the government financial status. This has another set of consequences. "What I am worried about is that the government giving money back in the hands of people will soon lead to double-digit inflation," warns Parag Parikh of the eponymous broking firm. "I would say that the sentiment has changed from pessimism to subdued optimism," he adds.

That said, across the board, market players expressed caution at Dalal Street's rapid jump upwards. Vikram Limaye, executive director, Industrial Development and Finance Corporation (IDFC), believes that the recent stockmarket run shouldn't be read as a clear signal of recovery. "Fundamentally, there is no significant improvement in earnings or earnings projections from corporates over the next two to three quarters. There's also no real trigger for this stocks rally and it may not be sustainable," says Limaye.

Abheek Barua, chief economist, HDFC Bank, sounds another note of caution—when compared with predictions of 3-4 per cent growth by the doomsday crowd, what is happening now is more realistic. "We're coming back to a middle path," he says, but credit data does not indicate a dramatic pick-up. "I think it has bottomed out but it's a very marginal improvement from a very deep bottom. Credit offtake is largely working capital-related, not really project-related. So I don't see what the optimism is all about," he adds.

Another unaccounted-for factor in the revival equation is India's monsoon-dependent agriculture. Thus far, international prices of agriculture commodities have not been affected by the global crisis. However, over the last five months, prices of some commodities have started firming up, a situation that could well ring alarm bells—it could raise inflation, fuelling another cycle of rising prices of food.

Broadly, the economy in India is reflecting the effort by government to revitalise spending by consumers and credit to industry. As Subir Gokarn, chief economist, Standard & Poor's (Asia-Pacific), puts it, there are some indications, including the happy sentiments, of a turn for the better, but these are "so fragile, they could turn for the worse easily." In hindsight, some of the over-reaction over the past 6-8 months is now abating. Whether this will lead to a new growth engine is debatable. Also, the election results are awaited. For now, it all goes back to Mr Kumar: will he vote with his wallet?