Palme d'Or winner Jafar Panahi was sentenced in absentia by Iran to a year in prison and a two-year travel ban due to "propaganda activities" against the nation. He won the Cannes Film Festival's top prize this year for "It Was Just an Accident".

“Cinema is a society. No one has the right to tell us what to do, and what not to do.”

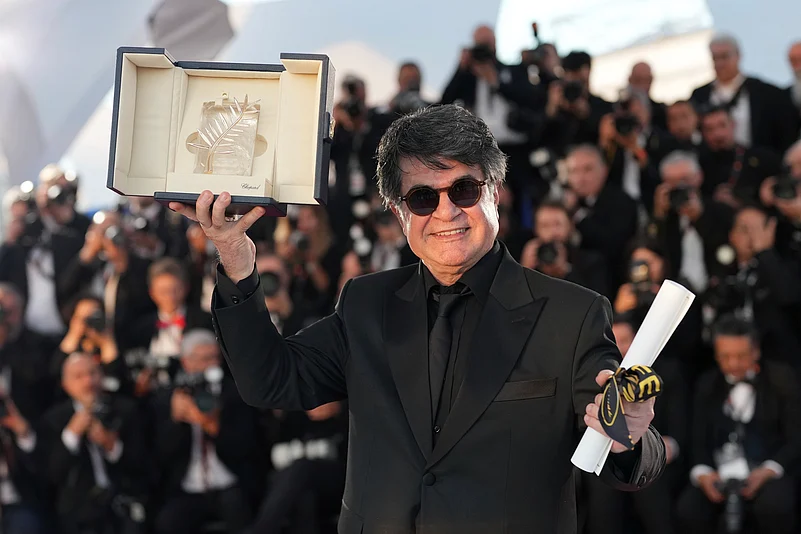

It was an overwhelming moment at the Grand Théâtre Lumière, Cannes. The hall shook with a standing ovation and fans of Iranian cinema across the world witnessed their favourite director take a quiet minute to absorb the joy of a hard-earned victory. As he received the prestigious Palme d’Or from the Jury Chair Juliette Binoche, Iranian stalwart Jafar Panahi, in unshakeable words, dedicated his award to those Iranian filmmakers who are not allowed to work by their incumbent regime. “I hope the moment we all long for and fight for reaches us soon, and we are no longer obligated to go underground to make our films,” he said. In his characteristic soft but firm style, he called upon fellow Iranians to set their differences aside and prioritise freedom in their homeland.

Panahi won the highest honour at Cannes in the official competition for his film It Was Just An Accident, a moral thriller where formerly imprisoned Iranian dissidents debate whether they should seek revenge from the man who used to be their captor and torturer. He is only the second Iranian filmmaker to win the Palme d’Or at the French film festival. Before him, another giant of the Iranian New Wave cinema, Abbas Kiarostami—who Panahi assisted earlier in his career—won the award in 1997 for Taste of Cherry. His recent victory makes him the fourth filmmaker globally, to receive the highest honours at the distinguished Big Three film festivals—Cannes, Berlin and Venice—following the likes of Henri-Georges Clouzot, Michelangelo Antonioni and Robert Altman.

But these achievements weren’t the only reasons that made this year’s Cannes special for him. After prolonged periods of incarceration and bans on international travel and filmmaking, this was Panahi’s first in-person appearance at Cannes in 22 years. At home, Panahi has been known to ferociously stand beside those who have been protesting against the authoritarian Iranian regime in the past few decades. In fact, appreciation for his latest triumph by the French foreign minister Jean-Noel Barrot also drew the ire of the Iranian government, who summoned the French chargé d'affaires in Tehran and lashed back at Barrot for his “irresponsible and instigative allegations”. Barrot had called It Was Just An Accident “a gesture of resistance against the Iranian regime's oppression.”

However, such political controversy isn’t new to the Iranian filmmaker. In July 2009, amidst the “Green Revolution” movement against the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Panahi was arrested while paying respects at the grave of Neda Agha-Soltan, a student killed during the protests. Though he was released after public pressure then, he was arrested again in March 2010—this time, for allegedly attempting to make a film on the protests. Initially out on bail, Panahi was eventually convicted for “crimes against national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic” and sentenced to six years imprisonment and a twenty-year ban on making films and leaving Iran. Following the conviction, he was placed under house arrest. In July 2022, Panahi was arrested and sent to Tehran’s infamous Evin prison for protesting the arrests of Mohammad Rasoulof and Mostafa Aleahmad, his fellow filmmakers. He was later released in February 2023, after he sat on a hunger strike. This was after Iran’s Supreme Court overturned his earlier prison sentence.

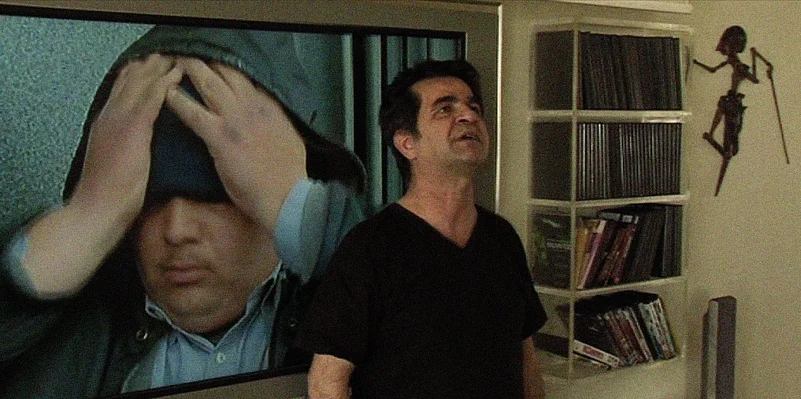

The incessant censorship and relentless state crackdowns have done little to dampen Panahi’s spirit; if anything, he has woven his cinematic oeuvre around this repression. He has shot It Was Just An Accident without seeking any permission from the Islamic Guidance Ministry or getting their approval for the script, which is the stipulated procedure in Iran. In 2010, after being banned from filmmaking, Panahi made This Is Not A Film (2011) in first-person documentary style along with Mojtaba Mirtahmasb. Shot on a camcorder and his iPhone, the film follows Panahi through his daily routine under house arrest, mulling over the meaning of filmmaking. This Is Not A Film sketches an incisive portrait of the circumstances that filmmakers must navigate for their art to survive in Iran. Smuggled in a USB drive, it was a surprise entry at the 2011 Cannes Festival and was eventually released in France.

Panahi didn’t stop at that—in 2013, he secretly made Closed Curtain at his summer villa. The film, with a Silver Bear-winning script, is a docu-fiction exploring the larger cultural subjugation of Iran through the filmmaker’s own state of mind. Then there was Taxi (2015)—which won the Golden Bear that year at the Berlin Film Festival—where Panahi goes around Tehran, pretending to be a taxi driver, just so he can lean into the encounters and lives of his passengers. Both 3 Faces (2018) and No Bears (2022), which star Panahi as himself, were also shot in a clandestine manner, while he was still banned from filmmaking.

The filmmaker’s works—like his Camera d’Or-winning debut feature film The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997)—bear the neo-realist imprint unique to the Iranian New Wave style right from the beginning. Progressively, Panahi has strengthened the social commentary around state repression in his films through creative means that stand out for their originality. The Circle (2000), Crimson Gold (2003) and Offside (2006)—all bear testament to these developments. However, the films that he has made post the travel and filmmaking ban have a distinctive impulse of resistance that organically communicates the material realities of socio-political oppression. The chosen mode of the docu-fiction form for a lot of these films seems to emerge from this very location, informed by the director’s own trysts with the State law. This is why, though the director refuses the label of being a “political” filmmaker, few in Iran have been able to paint a more accurate picture of the political quagmire that the citizens of the country find themselves in, than Panahi.

Reportedly, when asked if he would ever leave Iran and work in exile, Panahi has expressed an inability to survive in any country other than his own. “I just feel I don’t belong, and I can’t adapt,” he says, even though no moral judgement lies in his beliefs for those who have had to seek exile outside the country to be able to make films. “With the experience that I’ve had and with the person that I am, with the capacities and the incapacities that are mine, I just cannot leave Iran.” As Panahi returns to his homeland, armed with more international recognition than ever before, fans wait with bated breaths again to see if he will face the music of the powers-that-be for his undeterred love for cinema once more.