When Italian luxury brand Prada recently unveiled a sleek version of the Kolhapuri chappal, the internet exploded. Accusations of cultural appropriation flew around. Social media cried theft. Now, Prada is reportedly planning a limited-edition Kolhapuri-inspired collection in collaboration with artisans after facing backlash, according to officials from Maharashtra’s industrial body. But while the debates about aesthetics and credit went on, few paused to ask who still makes these sandals. And where? To answer that, one must turn away from Milan’s runways and step into a colony of craftsmen and families in northeast Mumbai. Here, in the cluster of leather workshops strewn across the lanes of Thakkar Bappa Colony, the Kolhapuri chappal survives, barely, but vividly.

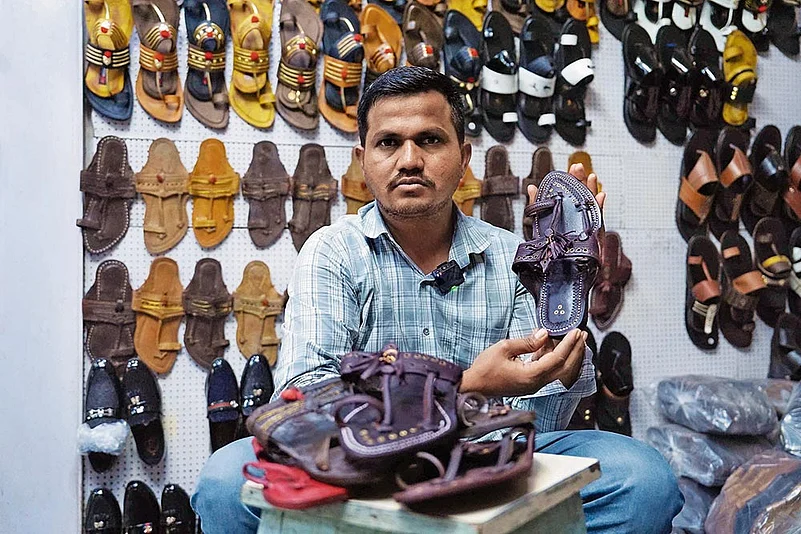

The narrow lanes snake between old warehouses, each corridor echoing with the clack of cobblers’ tools. Wooden boards lean against crumbling walls, their hand-painted signs reading Dillkhush, Janta, Jagdamba—places not of fashion but of memory, sweat and practice honed over generations.

Here, shop names flicker on tin boards, their paint bleached by monsoon after monsoon. Beneath them, artisans squat over their work, their palms darkened by dye, their eyes trained on curves, cuts and seams. This is where Kolhapuri chappals are born, or at least reborn. Not in the famed bazaars of Kolhapur, but in the interstitial spaces of the city, where heritage clings not to banners but to muscle memory. Under a faded red canopy, Vasudev Yeshwant Abhaynkar, 35, coaxes a leather strap into the arch of a sandal. The workshop smells of old turpentine, fresh glue and time. “These weren’t made in Kolhapur,” he says, dusting a finished pair, “but they’re still Kolhapuris.”

The pair on his own feet are feather-light, curved just right, the braided strap lying flat against skin. They were not made in Kolhapur, but in Jakrati, a village on the blurred Maharashtra-Karnataka border, where Kannada blends with Marathi and where generations of artisans have passed on their trade hand to hand. “I came to Bombay when I was 15,” Vasudev recalls. “My grandfather was in the chappal trade too. He once used bad leather—it ruined our workshop. After that, we moved here.”

In the colony around him, survival hums. There is the slap of chappals against concrete floors, the rustle of stitched soles, the laughter of children. Men sit, bent low over their craft. No one here talks of art. But everything here is art.

To understand Kolhapuri chappals, one must first understand Kolhapur. Once a princely state in British India, Kolhapur was a powerful economic and cultural centre. Known for its ornate jewellery, spicy cuisine and handloom textiles, it was also a thriving node for leather artisans, mostly from Dalit communities who worked in the shadows of social hierarchy. Here, the Kolhapuri chappal emerged not as a luxury but a tool—sturdy, practical and made entirely of leather. Every part, even the threads and embellishments, was crafted from natural materials. The leather was soaked in a mixture of jaggery, lime and salt, softened in river water, and dyed using local plants.

The chappals were loud. The heels slapped against stone pathways, announcing their arrival. Over time, the design diversified. Some had double soles, others single. Some curled at the tip, while others lay flat. Each pair moulded itself to the wearer’s foot, softened by body heat and sweat.

Kolhapuri chappals soon became famous beyond Maharashtra. Traders took them to Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and even the southern states. But the origin story stayed largely unchanged—each chappal was hand-crafted by families that had been doing this work for generations.

In 2015, Maharashtra introduced a stricter ban on cow slaughter, under the pretext of religious sentiment and animal protection. The law outlawed the sale and possession of beef and criminalised the slaughter of cows, bulls and bullocks. The move had a domino effect across various industries—but nowhere did it hit harder than Kolhapur.

Artisans who relied on leather from oxen found themselves without raw material. “We weren’t consulted,” says Pavan Vasantrao Powar, Head of the Charmakar Samaj Audyogik Sahakari Mandali. “They brought in the Gau Sanrakshan law and left us to deal with its consequences.”

The local leather market shrank. Tanning units shut down. The cost of leather rose from Rs 80 to nearly Rs 300 per square foot. Chappals that once cost Rs 150 now began at Rs 330. The more ornate ones, known as ‘antique’ for their traditional designs, shot up to Rs 2,500 or more.

“Transport stops. Leather gets fungus. What’s the use of a dry-region shoe in a wet city?” Vasudev asks.

As Kolhapur floundered, artisans across the border in Karnataka found themselves at an advantage. The villages of Athani, Madbhavi and Jakrati continued the craft without the same restrictions. Leather was available. Labour was cheap. The styles were similar, sometimes indistinguishable.

Vasudev explains, “There’s a difference. The heavy ones are made in Kolhapur. The soft, quiet ones? That’s us. Karnataka. But earlier, it was all one place. The court was in Kolhapur. That’s why the name stuck.”

In 2019, the Indian government granted the Kolhapuri chappal a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, recognising the craft as unique to a specific area. The tag included four districts from Maharashtra and four from Karnataka. Instead of resolving disputes, it blurred the lines further. Who owns the name? The design? The labour?

Kolhapuri chappals are not just handmade—they are caste-made. For centuries, they have been produced by Chamar, Dhor and Matang communities. These were Scheduled Castes, assigned the work of leather because it involved contact with dead animals, a task considered impure in traditional Hindu society. Yet, today, their craftsmanship is repackaged as ‘heritage’. Luxury brands and urban designers market their versions without acknowledgment. Artisans are paid per piece. Brands claim the designs. The credit, the profit, the ownership—all go elsewhere.

When Prada launched a designer version of Kolhapuris, words like ‘cultural theft’ and ‘appropriation’ were bandied about. But within India, appropriation wears local clothes. Upper-caste designers ‘revive’ traditions they never lived. Artisans are reduced to anonymous labour. Fashion magazines credit the Savarna creative director. Not the 60-year-old Dhor woman braiding the upper strap.

Pandurang Chavan and his wife still work from home. Their chappals are not expensive—but they are trendy, because they are real. Each pair takes a week. The braiding, the stitching, the dye, all done by hand.

One afternoon in Kolhapur, a visit to a one-room home reveals Sunanda Chavan, 48, sitting beside her daughter. She’s braiding leather strips, her fingers moving in rhythm as though following a tune only she can hear. “Once you start, your body remembers,” she says. She learnt it from her mother, who learnt it from hers. The men cut and stitch. The women “do the braids. The delicate parts. The soul of the shoe.” Each chappal takes 3-5 days. Some go to local shops, others to co-operatives. The earnings are modest, but steady. Nearby, Arun Krishnarao Satpute runs a workshop with barely a dozen artisans left. “Each one has debts of a lakh or two,” he says. He’s tried everything, applying for GI tags, lobbying for ITI courses in chappal-making, asking for subsidies. But leather is scarce. The youth are uninterested. Banks want collateral. Back in Jakrati, Vasudev’s family continues the old rhythm. His mother threads leather straps. His cousin delivers boxes to Dharavi. His wife manages the accounts. No one leads. Everyone works. “There is no patriarch in Kolhapuri chappal,” he says. “Everyone makes it.”

Every night, he wraps the day’s pairs in paper. The chappals are tagged, packed and loaded onto scooters that thread through Mumbai traffic. Sometimes they end up in boutiques in Bandra. Sometimes at a stall in Dadar.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Pritha Vashisth is Outlook’s Mumbai-based correspondent