It is difficult to ascertain a definite timeline to the birth of folk and tribal paintings in India; in particular to the emergence of painted scenes from the Ramayana. The obsession with finding exact dates is quite Western in its origin. In relation to these traditions, one should rather talk about continuities, transformations, and their contemporaneity instead. However, the Bhakti movement that began in south India, particularly Tamil Nadu, between 7th and 12th centuries, and reached north India by the 15th century is largely credited for the spread of Tamil and Telugu sessions of Harikatha (discourses on a saint’s life), and mendicants travelling across the lands, using painted scrolls as tangible visual aids to accompany their oral narratives of the epic traditions. It is this period that sees a proliferation of tradition, and it is logical to presume that folk and tribal paintings like West Bengal’s Patua and Patachitra scrolls or Andhra Pradesh’s kalamkari traditions are when Ramayana scenes begin to figure in, says the doyen of Indian and tribal and folk art traditions, Molly Kaushal, Prof. of Performance Studies and Head of Janapada Sampada Division IGNCA,

Around the 16th century, Mughul influences Emperor Akbar’s Persian Ramayana manuscripts and illustrated miniatures, including the Persian treatise Ramcharitamanas by Tulsidas, followed by Ramayana themes portrayed in Company style, Rajasthani (Bikaner, Bundi, Udaipur/Mewar, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Kishangarh, Kota) and Pahari (Kangra, Guler, Basohli, Mankot, Mandi, and Jasrota) schools of miniature paintings.

Numerous versions of the Ramayana exist amongst the Indian tribes e.g. the Bhils, Mundas, Santhals, Gonds, Sauras, Korkus, Rabhas, Bodo-Kacharis, Khasis, Mizos, Meiteis, etc. Tulika Kedia, who founded Unique Creations and Arts Gallery, in Delhi in 2010, lists a couple of factors that set the folks and tribal Ramayanas apart from miniatures and other mainstream versions. “While retaining the structural and thematic unity of the text, these communities weave their own plots and subplots into the texts and arts. The physical and socio-cultural landscape acquires a unique native character and defines the sacred geography of the region that the tribes reside in. Linking the Ramayana with local geography and rituals; by incorporating songs, narratives, and art forms from the native repertoire, by making the characters follow the moral and ethical codes of the community, each tribal group renders its version of Ramayana through art. These tribal versions of Ramayana through art are much simpler, naïve, and rustic as compared to the Mughal-Persian and Company styles.”

The folk and tribal painterly traditions comprised scrolls with a singular theme or a litany of vignettes or panels narrating one kand or kands (episode/s) of the divine being in focus, e.g. Ramcharitamanas, Hanuman Chalisa, etc. Usual kands (episodes) from the Ramacharitamanas include Ram darbar (court of Ram), madhur milan (Ram-Sita’s first meeting); Sita’s swayamwar (choosing a husband), vanvas (the 14-year exile from Ayodhya) that includes chasing Mareecha (Ravan’s ally, masquerading as deer), Hanuman visits Sita in Ashoka Vatika, etc. Some traditions like Mithila paintings, the characters are discernible also by their clothes, accessories, and skin tone as they have the same height, built, and facial features. In Phad paintings, no character faces the audience. All side profiles, locked in each other’s gaze. Cloth, khadi, paper, silk, canvas, are materials painted on using natural dyes, usually made by the artist themselves. The work is often not a solitary exercise. The master artist outlines the central figures, while the women and children of the household colour in the gaps.

Most of the tribal and folk artists are themselves ardent devotees of Ram. For instance, Mithila artists view the Ramayana as the primordial truth, the fact, and that Ram and Sita met in Madhuban (Forests of Honey), Bihar. Legends say, Janak, king of Mithila and Sita’s father, had approached an artist of the Mithila art form to paint the palace walls during his daughter’s wedding to Lord Ram from the neighbouring Awadh. The walls became lush with thickets of bamboo, mango and lotus, and fauna like birds, fish, and snakes, consciously coupling. It is why the artists feel it is their responsibility as devotees to keep the parampara (tradition) alive. “Every groom is looked at as Ram, and his wife as Sita. All daughters in Mithila are Sitas and the people from Awadh, where Ram is from, are our brothers. We paint with our arpans (rangolis) and our Ramayana paintings with bhava (emotion). So much so that while painting, if tea is served, we stop the work, finish the tea, wash our hands, and only then resume the work,” explains Vijay Jha, a Mithila native, exhibiting at stall no. 72, Dilli Haat, Delhi. Jha proudly shows a madhur milan painting that shows Sita and Ram on either side of the same flower, reaching out to pluck it as her attendants watch while holding their puja thalis. Jha strongly believes that this kand took place at the gardens of Girija mandir that houses Raja Janaka’s Kuladevi (clan-deity), which lies in present-day Phulhar, 20 km from his hometown.

“From Ram, I learned to maintain all kinds of relationships. From Ram-Lakshman, I learnt of brotherly love, and from Ram and Sita, the perfect husband-wife union,” says master artist Rabindra Bhehra of the palm-leaf, tussar silk and canvas traditions of the Pattachitra. He won the national award in 2008 for his painting titled Punchbhut Mein Ramayana which showed the five elements of nature connected to the characters of Ramayana. It took him five years to complete the 4x2ft painting. “We read and study the Ramayana, as if taking an exam, so the story always stays on our mind. We create what we read. If the concentration wavers while painting, we immediately stop the work and start a new task to regain focus.”

The nomadic Bhopas (male priests) from Bhilwara, Rajasthan, would sing kands from the Ramayana using Phad paintings as props, where the Bhopi (priest’s wife) would dance and shine a torch on the section being narrated. These paintings are on the Ram Dala ki Phad (Ram’s group) – episodes on Ram, Krishna, and Vishnu. Every Ramayana painting is started by drawing Ganesha, his consorts Riddhi-Siddhi, the Dasvatar of Vishnu with Ram avatar at the end, and from there on the Ramayana stories begin. Before starting a painting, the artists pray to Pabuji, a folk deity of Rajasthan, or Devnarayan, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and then a virgin girl will draw “the swastika” or “the first brushstroke”. “For us, Ram is Maryada Purshottam, the perfect human in whose footsteps we must follow. He was to get the rajya vishya, but the next moment was exiled. Yet, he obediently gave up his throne. We could learn from Ram, especially now, when property disputes between siblings have become common,” says Kalyan Joshi, whose father is Padma Shri awardee Lal Ji Joshi, who opened Joshi Kala Kunj school in their hometown to revive Phad. Kalyan himself won the National award for his 4×10 feet Ram Dala ki Phad in 2010, to resurrect the art form after the Bhopas had stopped giving performances.

And there are lesser-known folk forms painting Ramayana themes. Like the 2,000-odd Thakar tribe at Pinguli village in Sindhudurg district, Maharashtra, who have their own version of the Ramayana, called Thakari Ramayana. It begins with Sita’s swayamvar and ends with Ram’s victory over Ravan. For instance, in one episode, Shambhu Kumara, the son of Ravana’s sister Shurpanakha, was performing austerities upside down for close to 14 years in the Panchavati forest, when Ram, Lakshman and Sita on their exile, unknowingly came to dwell close to. It so happens that Lakshman, while making his way to pluck fruits, cuts through the thicket that had grown on Shambhu Kumara, thus injuring him. While Lakshman scurries off, his mother rushes to him. To avenge her son’s wounds, she transforms into a beautiful woman. An enticed Lakshman agrees to marry her but wants Ram’s consent. But Ram sees through her disguise, and warns Lakshman, and instructs him to cut her nose and hair and send her back to Lanka. In the popular Ramayana, Shurpanakha falls in love with Ram instead, and hurls abuses at Sita, at which Lakshman chops off her nose and hair and bundles her off to Lanka.

Many in the tribe today, are largely craftsmen, who use Kalsutri Bahulya (string marionette) to recite Sita's swayamvar, while Dayati (shadow puppetry) and Chitrakathi (painting) to demonstrate scenes from the vanvas. It is said that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj once summoned a tribe member, Vishram Gangavane, and employed him to spy and collect information for the kingdom, knowing the wandering musician visited every house in the region to perform. On seeing the art form die slowly, Gangavane’s great-grandson Pashuram, made many efforts to preserve it, including Thakar Adivasi Kala Angan (Museum & Art Gallery) in Pinguli. He was duly rewarded with a Padma Shri last year.

“But even this year, he will give his usual performances at the temple,” says his son, Chetan, about his father’s performances of the Chitrakathi Ramayana every day of Navratri at the Kelbai Devi Mandir, Kudal, and for Diwali at a mandir in Kumbarwadi. “In front of Ram, we are nothing. He was the mode of survival for my ancestors who earned their daily bread by performing the Ramayana. For 25 years now, I have watched my father and brothers recite the Ramayana every year on Diwali, and yet there’s a crowd,” says Chetan. Most male members of the family, like his uncles Jairam and Aatmaram, have ‘Ram’ in their name.

A dot in the ocean compared to the Thakars is the Jogis or Bharatharis of the Pauva caste, in Gujarat, as only 25 of them are continuing the art, defined by fine strokes and heavy stippling. The wandering tribe—originally from Rajasthan, who relocated to Gujurat after upper-caste men snatched their lands—would sing bhajans in the wee hours of the morning to rouse the farmers. Govind Jogi, one of the artists, says Ram na ban vagya mune hari na ban vagya by Gujarati folk singer, Diwaliben Bhil, was a popular bhajan, in which Sita yearns for Ram, hoping to be struck by his arrow that shoots off either from his eyes or soul. In the 1970s, cultural anthropologist Haku Shah had initiated Govind’s parents, Ganesh and Teju, into drawing. Initially, Teju had fashioned a reed from wheat leaves to paint with mud, on cloth, paper and canvas, but of late, uses a ballpoint pen. Being illiterate, she learnt the Ramayana by hearing her elders recite the kands. “And her memory is good,” vouches her son, Govind. Her technique is best gauged from her painting of vanvas, with Ram, Sita and Lakshman shown sitting outside their kutiya (hut), admiring the birds and animals pottering amidst a variety of foliage. “There is no one greater than Ram. I keep him in mind when I paint, praying throughout that the painting should not turn bad,” says Teju.

But all folk and tribal traditions worship Ram. Like, the globally recognised Warli and Gond art. The nature worshipping Warlis of Maharashtra, noted for drawing triangular human forms in rice paste over on gobar (cow dung) washed walls, give precedence to their clan-deity Kuladevta, Mahadeva and Ganesha over Ram. Ram is only evoked when a newly wedded couple has to throw a party for clan members to socially gain acceptance of their union. Only then, the groom is allowed to complete the ritual by saying “Ram Ram”.

For Pradhan Gonds like the award-winning Gond artist, Venkat Raman Singh Shyam, from the Patangarh in Dindori district, Madhya Pradesh, their prime god is Lakshman, not Ram. The Gond Ramayani, as it is called, has seven themes dedicated to Lakshman, which Gond artists religiously paint, and would use during their singing discourses. These include Lakshman’s trial by fire; a smitten Indrakamani abducting Lakshman; Lakshman and Princess Machladei; Indra’s daughter Tiryaphool and Lakshman; Ravan’s daughter Rani Puphaiya and Lakshman; Vasuki’s daughter Bijuldei and Lakshman; and Lakshman undertaking the banishment of Sita. “Lakshman is the sheshnag ka avatar (multiple-headed serpent), and we Gonds are snake worshippers,” explains Venkat, who started painting at age 13 under the tutelage of his famous uncle, Jangarh Singh Shyam.

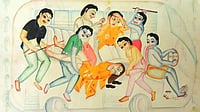

Venkat’s art for introducing contemporary themes in Gond paintings can be gauged through a recent work of his, which shows Ravan on one side, atop an elephant, geared for war, and Ram and Lakshman on the other side, dressed in Western wear, suspiciously from the Victorian era, in counter stance. “No one has seen Ram or Lakshman. So we don’t know how they look. There are theories they belonged to the Aryan race. And Aryans are supposedly tall, fair-skinned, with long pointed noses,” he says. In his book, Finding My Way, there’s another painting, this time of the Pandavas entering the Kamyaka forests after they were exiled too, with cameras in tow, shooting and hunting for wildlife species.

Prof. Kaushal says that market relationships and the economy of these painting traditions have changed, which is what keeps them afloat. “For example with the artists of patam katha tradition, the mobile shrine used in narrating the Kula Puranas, were dependent on upper caste patrons. But those relationships are already on their way out because the artists no longer rely on these patrons. The painting has been cut off from the tradition and the many ways that were responsible for its existence. People are earning more money by just making a small frame out of the entire scroll, and selling it at Dilli Haat and other such urban centres. The art has been revived by a new economy, and they haven’t evaporated but taken the form of new contemporary traditions.”