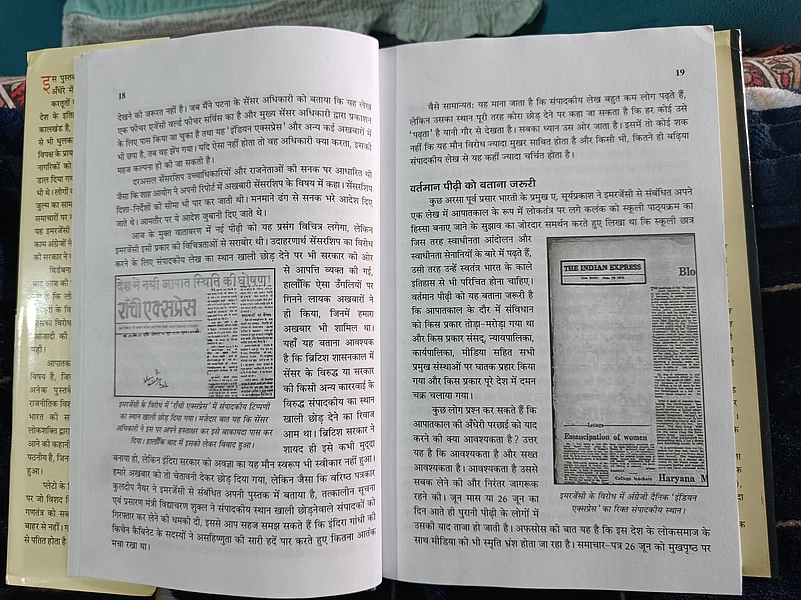

During the 21-month-long imposition of the Emergency―from June 25, 1975 to March 21, 1977―there were a handful of newspapers that registered their protest. They did this by leaving their editorial spaces blank. The Ranchi Express was among them.

This newspaper, which began publication in 1963, was the only newspaper to be published from Ranchi in the then united Bihar. Interestingly, its blank editorial space also carried the signature of the censor officer, a fact that is documented in the book Emergency ka Kahar aur Censor ka Zahar.

The book is authored by Balbir Dutt, a senior journalist and founder of Ranchi Express. Recalling those days, Dutt says, “I was the editor of the newspaper during the Emergency. The censor officers were ordered to allow the publication of the newspaper only after going through all the news. It was the second or third day after the declaration of the Emergency. The magistrate deputed for our newspaper read everything carefully, even the report of a football match between two national teams, but he probably overlooked the editorial column that we had left blank. Unknowingly, he put his signature even in that blank space. When the column was printed the next day, there was a huge furore.”

Dutt, nearly a nonagenarian now, narrates another interesting incident. “In the last three months of the Emergency, things were more relaxed. Indira Gandhi had come down to Ranchi to address a public gathering at the Morabadi Ground. I was seated in the front row of the press gallery. At one point, when Gandhi was criticising JP [Jayaprakash Narayan], she was hooted down by students who belonged to the Nav Nirman Samiti. So raucous were their shouts that it became difficult for Gandhi to continue her speech. Turning to us, she said, “Press people, do you see what is happening here? These people won’t let me speak.”

The following day, the newspapers devoted more column inches to the booing and heckling faced by Gandhi than to her speech. What happened at the Morabadi Ground was unprecedented. It surprised people that it happened to a powerful leader like Indira Gandhi and they perceived it as a big setback for her. Gandhi had addressed several election gatherings across states during this period, but prior to this, no such incident had ever been seen or reported.

Patna occupied a more prominent place in the narratives about the Emergency. In March 1974, it was the centre of the great upwelling of students under the leadership of JP, which gradually turned into a nationwide movement. The rampant use of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971, and the imposition of the Emergency by the Indira Gandhi government was, to a large extent, a response to this movement.

Due to the visibility of the JP movement, events and incidents happening in other cities of Bihar got little to no coverage in the newspapers published from the capital city of Patna. But Hazaribagh and Daltonganj jails were filled with political agitators.

Emergency ka Kahar aur Censor ka Zahar describes the Emergency as a horrific period in the life of the country. Dutt believes that only those who did not witness it, let alone suffer because of it, can be naive enough to call the present regime (Modi’s 10-plus years of rule) an “undeclared Emergency”.

But Inder Singh Namdhari (85) and Saryu Rai (74), who worked with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) during the Emergency and went on to become top leaders and ministers of the Bharatiya Janata Party, beg to differ. Namdhari is a veteran of Indian politics. He was incarcerated at the Daltonganj jail for 17 months during the Emergency. He was also lodged in the Hazaribagh jail for a few days just before the Emergency, because he had played an important role in the two-day Bihar bandh called by JP.

The MISA Act was slapped on Namdhari, so he remained behind bars until the end of the Emergency. When the Emergency was declared, he initially hid in a Gurdwara in Punjab for a few days, but as soon as he returned home to Daltonganj, he was arrested.

As someone who saw and suffered under Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, Namdhari finds the conditions in the country today now similar to a large extent. He says, “Putting a sitting chief minister in prison is not a trivial thing. The way the farmers’ movement was suppressed, and the way a student like Umar Khalid has been kept in jail for years altogether without any grounds and without even allowing him a bail―all this mirrors Indira Gandhi’s Emergency.”

Rai, an underground worker for the RSS during the Emergency, used to edit the Lokvani magazine. He would attend the RSS meetings in Chennai (Tamil Nadu) and Gujarat, because these states were not ruled by the Congress. He tells us that during the Emergency, his house was raided once, but he managed to get away because he was sleeping on the roof that day.

Rai lists some differences between Gandhi’s Emergency and the situation today. “The rules introduced by Indira Gandhi during the Emergency were followed strictly. For instance, trains used to run on time, schools used to open on time, the staff used to report for work on time. There was no corruption. If you compare that with the way things are now, you will find that rules are flouted and there is corruption everywhere. I am not saying whether it [the Emergency] was good or bad.”

(Translated by Kaushika Draavid)