Drug seizures in India are rarely front-page news, and ’70s hippie favourite heroin has perhaps even fallen off the radar with the Narcotics Control Bureau in India. So a seizure of 26 kg of the drug by the Punjab police last fortnight would have been just a couple of inches in the inside pages if— the ‘big if’ had come true—it hadn’t been for the names of Vijender Singh, Olympic bronze medallist and poster boy of Indian boxing, and his coach-cum-sparring partner Ram Singh cropping up in connection with the drug-runners.

Once their names were taken, the national media was naturally all over the story. Suddenly, the Punjab drug story was dusted and rerun. Wasn’t it, after all, “the new transit point” for the international drug trade? Reams of print and TV footage was devoted to the fact that the porous Indo-Pak border has become a favoured route for smuggling drugs in from Pakistan and Afghanistan for new millennium drug syndicates.

The pugmarks of ex-cop and wrestler-turned-druglord Jagdish Pola—an influential racketeer well-known in sports and entertainment circles—seem to be all over the present case. The mystery man moves around in swanky cars, has a very expensive lifestyle and has lots of links in Canada. Investigators working with Anoop Singh Kahlon—the NRI smuggler arrested with the 26 kg of heroin from Mohali—say Pola is absconding. Meanwhile, Kahlon revealed the name of Ram Singh, who in turn implicated Vijender. The drug haul suddenly had a star athlete link.

The police also arrested pharmacist Sunil Katyal from Ludhiana. Working for a private company, he was a close associate of Kahlon and used to conduct “authenticity tests” for international drug smugglers. He would test drug samples at his firm’s laboratory for a fixed commission. Pola, who joined the trade a few years back, apparently became head of Punjab operations. Kahlon too prospered in this time, acquiring huge properties in and around Punjab.

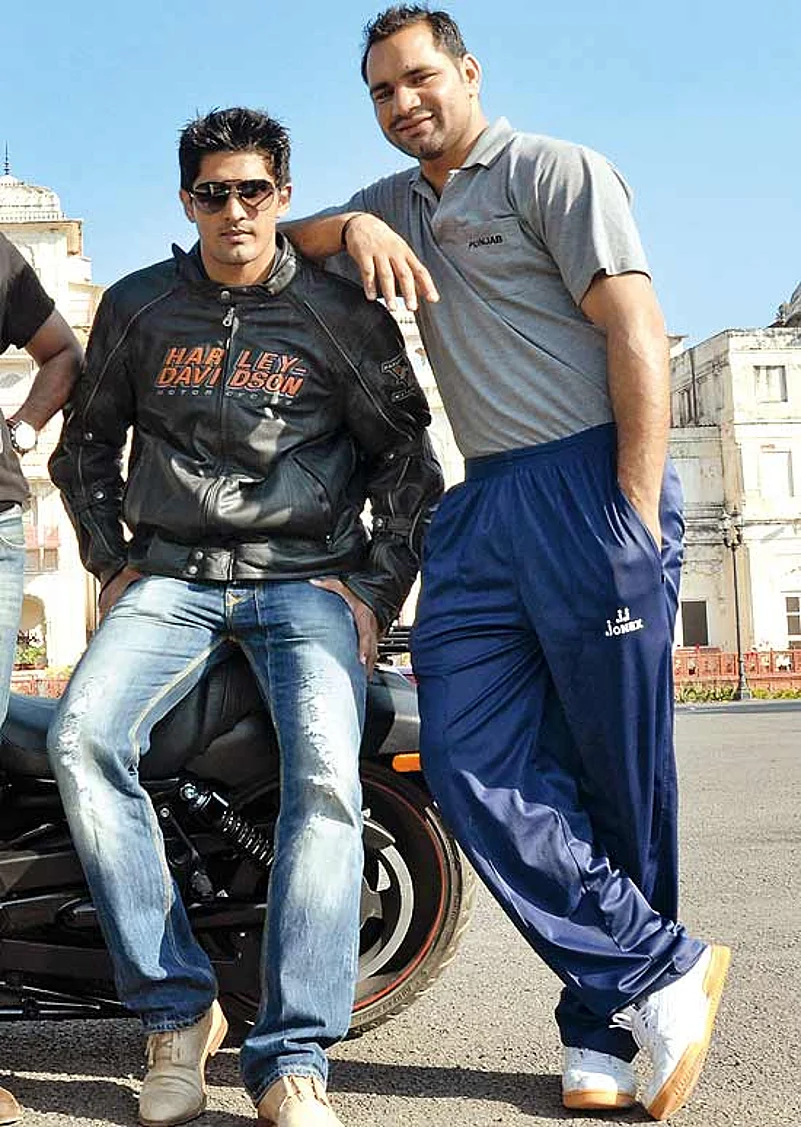

Photograph by Jitender Gupta

Police sources say for now it looks like Vijender does not have any clear links to the drug mafia and their illegal operations. He and Ram Singh seem to have been merely recreational users. Vijender apparently was occasionally “accessing the drug since December 2012”. More than him, what the police is probing are the international links of Pola’s gang. Punjab additional DGP, Intelligence, H.S. Dhillon, told Outlook: “We are in touch with the Canadian authorities. There are leads that the drug (in this haul) were meant for an international deal. Revealing any more at this point would be counter-productive as the probe is still going on.”

But public and media curiosity is all about Vijender and Ram Singh’s role. Were the two just occasional users or was there something more sinister to their proximity to the case? Since both knew some of the key members of Pola’s gang, did they also invest in the racket? Commenting on their role, Dhillon says, “They got into it for the adventure. Investigations so far show they have not invested anywhere and also have no knowledge of the syndicate—they knew Kahlon since December though.”

The Punjab drug mafia’s Canadian link (thousands of Punjabis have migrated to the country) is perhaps what has led to it becoming a vital conduit for international drug syndicates. Sources in the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) confirmed that the US has tightened security since 9/11, which made it difficult for the drug cartels to bring in drugs into the country through the old overland routes like Mexico.

Canada, on the other hand, is still largely untapped territory and with the many Punjabi immigrants there, with strong roots back home, this link is being exploited. Indeed, Punjab’s geographical position and its porous border on the west makes it a goldmine for international gangs. Some of the drug also finds its way to the domestic market. “Punjab is a transit point. If a gram of heroin costs Rs 1,000 in Punjab, it would be Rs 10,000 in Mumbai and Rs 20,000 in Delhi while in the international market it would fetch Rs 2 lakh,” says NCB deputy director-general B.B. Mishra. From these bases, the drug is shipped to the western centres. Canada, the big new destination, is just a step away from the US markets.

Sources say the land route across the border with Pakistan has become popular since the old sea route to the Maharashtra and Gujarat coasts have become risk-prone with the coastguard very active after the 26/11 attacks. In the ’70s and ’80s, D-Company would use the sea route for landing the drug which was then transported to Mumbai to be shipped abroad. But with Dawood Ibrahim’s power on the wane, the heroin runners have resorted to routes used during militancy in Punjab to bring in arms from across the border.

A major fallout in all this has also been that drug abuse in Punjab now is at an all-time high. Obviously, some of the heroin—adulterated to enhance profits, say sources—is being routed to the home market. (Remember Rahul Gandhi’s controversial statements last year that a majority of Punjab’s youth are becoming drug addicts?) And those getting hooked to the drug are not the upper middle class in the cities. They are young people everywhere, especially in rural areas, who find they have easy access to the substance. Now heroin is an expensive habit and what this is doing to the families of the victims is anyone’s guess.

By Chandrani Banerjee with Amba Batra Bakshi