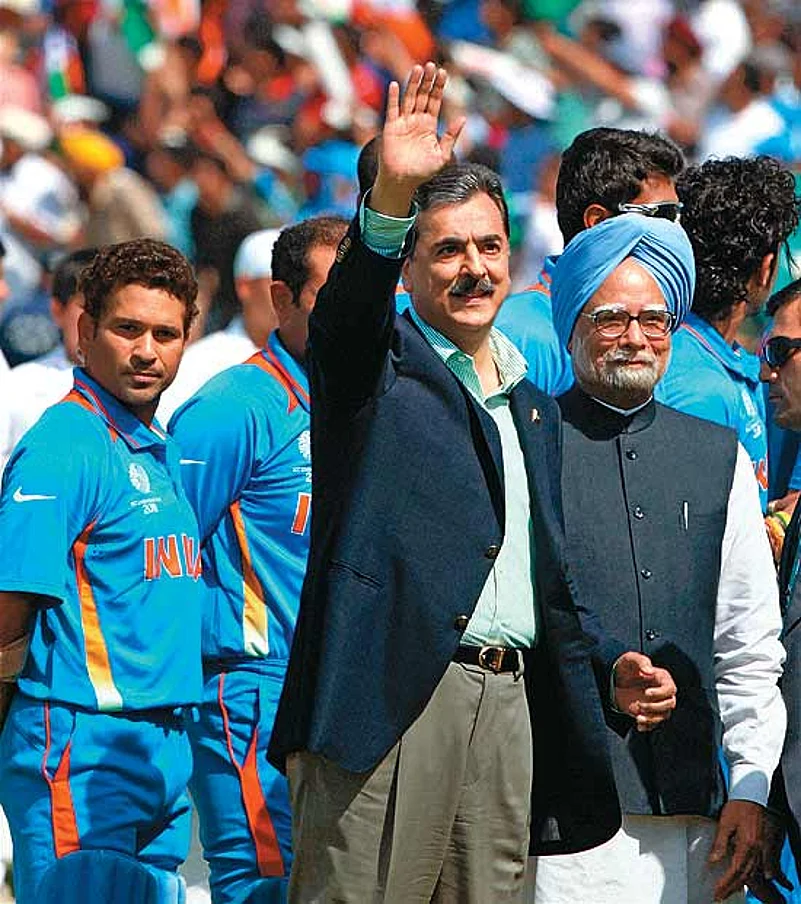

Away from the breathless excitement and nail-biting tension of the India-Pakistan semi-final match, the mood inside the Long Room at the Mohali cricket ground was remarkably different—warm, poetic and contemplative. An encounter of another kind was afoot here, a meeting over dinner between Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his Pakistani counterpart, Yousuf Raza Gilani. Flanked by Congress president Sonia Gandhi and her son, Rahul, Manmohan Singh recited an Urdu couplet to welcome Gilani and his entourage. It set the mood for the two sides to partake of the lavish spread—and for informal parleys. Gilani too responded with a couplet and profusely thanked the Indian PM for hosting him as also creating the opportunity for the two countries to interact at the highest political level.

Manmohan spoke extempore at the dinner. A senior Indian official present at the meeting told Outlook, “He spoke straight from the heart, but it wasn’t all emotion.” He acknowledged the many difficulties in establishing normal and cordial relations, but stressed that this goal both India and Pakistan “owed to themselves and their people”. Striking a protagonistic vein, he said it was for the leaders to take the initiative to improve ties, instead of waiting for outsiders to nudge them towards it. Gilani, in turn, emphasised his country’s commitment to have good relations with India and hoped that all outstanding issues between them would be resolved through the dialogue process agreed upon in Thimphu, where the foreign secretaries had met on the sidelines of SAARC.

It could well be said that March 30 was a day of triumph both for cricket and diplomacy, the two often consciously brought together from the time of Jawaharlal Nehru. These attempts in the past have, at best, resulted in temporary improvement in Indo-Pak relations, so is Manmohan’s invitation to Gilani any different? “Each such invitation is different because the context is always different,” says Congress MP Shashi Tharoor. “Coming after two-and-a-half years of suspended dialogue following 26/11, this invitation is particularly significant. It accelerates a process of normalisation that the Indian government had for a while been reluctant to commence.”

Before Mohali, mandarins in the foreign office had understood the need to give a political push to the decision for resuming the Indo-Pak dialogue process. Yet there was a catch—Manmohan couldn’t travel to Islamabad, or invite Gilani to New Delhi for a summit meet unless there were concrete achievements to flaunt, particularly on the issue of terrorism. Worse, the volatile public mood post-26/11 precluded the possibility of registering a breakthrough in Indo-Pak ties. The semi-final, therefore, became an alibi for the two PMs to meet officially and take a step forward to normalise relations.

South Block officials say Manmohan was quick to seize the opportunity as soon as India beat Australia to earn a berth in the semi-final. He shot off invitations to Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and Gilani to watch the match in Mohali, surprising most of his cabinet colleagues and senior officials. Says a senior official, “This plan must have been in his mind for a while because he tried to put it into action from the moment it became clear there will be an India-Pak clash in the semis.”

Equally surprised were the Pakistanis, who couldn’t have turned down Manmohan’s invitation as it would have showed the country in a poor light and portrayed its leaders as cussed. Islamabad communicated the decision to Gilani, who was on an official trip to Samarkand in Uzbekistan, and once he expressed his willingness to travel to India (after his return), his acceptance was formally transmitted to New Delhi.

Manmohan’s cricket diplomacy had elements of a subcontinental batsman’s deft touch. Pilloried in the media on the issue of corruption, he exploited the excitement preceding the match to bag for himself, quite unexpectedly, some favourable news coverage. For a good many days, people were speculating on the outcome of it all, wondering about its efficacy and perhaps a tad apprehensive about the reactions. In the end, though, Manmohan’s political instincts were proved right—there were loud cheers from the Mohali crowd for the Pakistani national anthem, indicating that at least at a popular level there still remains a lot of goodwill for that country.

“I see it as a very welcome gesture,” says author Urvashi Butalia, who has close contacts with people across the border and has written a book on the trauma of Partition. “There is nationalism when India and Pakistan play but this time it was not that high as everybody wanted to see a good match.” Butalia feels such gestures will help strengthen people-to-people contact, paving the way for regular and frequent travels across the border. Agrees journalist Kumar Ketkar, “Any opportunity for India and Pakistan to come together should always be taken. Cricket is a religion common to both countries. It not only brings the two nations closer but also helps in healing existing wounds and releasing tensions.”

We are family.. A banner seen at the Mohali semi-final match. (Photograph by Biplab Banerjee/Asian Age)

Such sentiments, obviously, aren’t shared by the Indian intelligence agencies. At least two journalists who came from Pakistan to cover the match were evicted from their hotel rooms once their nationalities became known. Hotels were under pressure from police to refuse accommodation to visiting Pakistani scribes. One of them, Zahid Malik, told Outlook, “What’s the use of making all these announcements at the level of the prime ministers if at the ground level this is what the officials do?” Another Pakistani journalist spoke about his harassment at the hands of an Indian intelligence agency whose officials barged into his hotel room and grilled him for over 30 minutes with “aggressive questions” on why he was in India.

Amidst the horror stories there were also redeeming ones. Like the retired army officer who gave journalist Ehsan Qureshi a room in his house after the latter couldn’t find a place in any of the city hotels. The officer had been wounded in Kashmir during the 1965 war against Pakistan. Says Qureshi, “He treated me like a brother, let me stay in his house and was willing to invite any other Pakistani journalist who didn’t have a place to stay.”

Are we then to conclude that Manmohan’s gamble to invite Gilani is in consonance with a latent desire to forge better relations with Pakistan? Says Tharoor, “It’s early days yet. One six doesn’t make an innings and one cricket-watching summit doesn’t transform an entire relationship. But it’s been a solid, constructive initiative.” Perhaps it was the salutary mood that helped the home secretaries of the two countries reach a vital agreement a day before the Mohali match—an Indian commission will soon visit Pakistan to take forward the 26/11 investigation; a judicial commission from Pakistan will come to India in connection with the ongoing trial there. In addition, New Delhi agreed to update Islamabad on the Samjhauta Express probe, and the two sides also decided to establish a hotline for sharing information on terror threats in real time.

Much will obviously depend on the prime minister’s ability to consolidate the gains accruing from this impromptu ‘peace’. Says a senior Indian diplomat, “It is the PM’s personal conviction and deeply held faith that India and Pakistan can live peacefully and lead a normal relationship like many other neighbours.” Yet Manmohan’s ability to translate his conviction into reality is dependent on two factors. For one, can his government, beset by corruption charges, focus on the complicated elements of Indo-Pak relations? Political analyst Mahesh Rangarajan says Opposition leaders, including BJP leader L.K. Advani, have felt compelled to welcome the cricket diplomacy, albeit cautiously. “But we will go back to dal-roti politics from Saturday, after the finals in Mumbai,” Rangarajan adds.

The second factor is Pakistan’s behaviour. Should India witness a terror incident, the Mohali spirit would likely melt overnight. Sources fear such an attack could occur in Afghanistan, where voice intercepts suggest an ISI conspiracy to yet again target the Indian mission in Kabul. For the moment, the Mohali spirit has buoyed Indian officials who seem affected by the PM’s optimism. But they have their feet grounded. As one of them said, “It is said that God took seven days to create the world. It doesn’t need second-guessing to say it will take much longer to mend India-Pakistan relations.” Diplomacy, even that inspired by cricket, we all know, can’t be a one-day affair.

By Pranay Sharma in Delhi, with Rohit Mahajan in Chandigarh