It’s a sight that is both mesmerising and inspiring. Thousands and thousands of people stalking the streets of different Arab countries, united in their collective fervour for democracy and economic uplift in a region notorious for despotic regimes. A hitherto quiescent people have risen in revolt, much to the nervousness of their authoritarian rulers. Who can ever argue against the change seemingly imminent in a land where protests and Islamic terror have tended to become synonymous? It’s the reason why we, in India as also around the globe, hope the high tide of democracy washes over the land of Arabs.

At Ground Zero, though, the picture is fuzzy. Take Oman’s desert town of Sohar, which erupted in protest against the ruler on February 28. As we in India applauded the protest shown on TV, armed gangs walked into the Lulu Hypermarket, an Indian-owned chain with 87 outlets all over the Gulf, and set it ablaze. Neither the police nor the fire brigade intervened. Worse, local Omanis looted the hypermarket. Was the democratic upsurge also articulating incipient anti-Indian feelings?

No, says Anil Wadhwa, India’s ambassador in Muscat, Oman’s capital. “It was an act of vandalism by a small section who come from outside,” he told Outlook. Satish Nambiar, chairman of the Indian Social Club in Muscat too insists it’s a misreading: “Oman has been India-friendly. Sohar was an isolated incident, there’s nothing to worry about.”

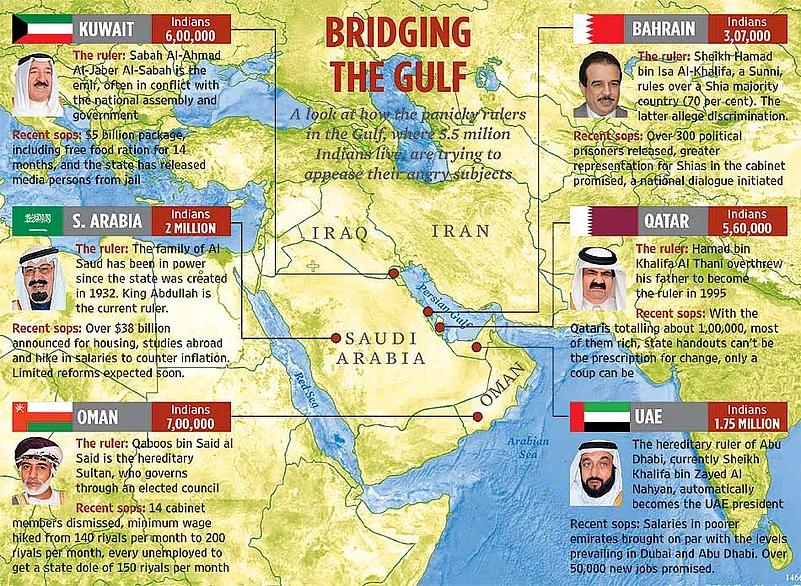

An isolated event it may have been, yet Sohar underscores the possibility of the winds of change blowing away the interests of 5.5 million Indians (and with it India’s) who live and work in the six Gulf countries, which together constitute the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). They remit a staggering $32 billion every year. All this could go up in smoke, says a Dubai-based Indian businessman in the perfume industry. He explains, “Democracy in the Gulf countries may not necessarily be a good thing for Indians since it is naturally going to be propelled by a strong dose of nationalism. This means there will be pressure on the rulers to transfer jobs to the locals. Second, business demands stability. And if the change in the region is tumultuous, our business will be affected.”

Upheaval in the GCC countries could impact the two-way trade worth $110 billion between them and India, and disrupt the energy supply to India, which sources 90 per cent of its demands from the region. And should a Libya-like scenario develop there, imagine the gargantuan problem of evacuating 5.5 million Indians. No wonder then, the Indians here are ambivalent about the thirst for democracy. Having no permanent stake other than earning petro-dollars, and not a participant in politics, they find the idea of revolution quite scary.

| Bahraini anti-government protesters throng the streets of Manama |

And though Yemen isn’t part of the GCC, sustained street protests here have acquired salience because it’s part of the region—it is thought that a successful revolution there could well fire the imagination of people in the neighbourhood. Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh, in power since 1978, has tried to mollify the population through a declaration that he wouldn’t stand for president at the expiry of his term in 2013. Yet the situation remains “very volatile” there. Says Damodar Thakur, a professor in the University of Saan’a, “Things are at the crossroads. Protests here are peaceful and they are not against Indians.” With arms freely available and the country a battleground for Al Qaeda, Thakur throws a caveat, “If it degenerates into an armed struggle, then the situation will deteriorate fast.” It could compel India to evacuate some 14,000 of its people.

Ultimately, the change in the Gulf will crucially depend on the possibility of the democratic upsurge washing over Saudi Arabia, say analysts. It’s the region’s most powerful country, boasting formidable economic and military muscle and has a cultural resonance because of its holy cities of Mecca and Madina. It could therefore become the bulwark against the unrest spreading; conversely, should it keel over under popular uprising, the political arrangement in the Gulf would be transformed. “The dust storm in the Arab world is yet to settle down,” Usamah M. Al-Kurdi, a three-time nominated member of the Saudi Majlis Ash Shura (parliament) told Outlook.

In this maelstrom of demands for liberty, experts are poring over the annals to discern the inclination of the Saudi people to protest and ask for reforms. This has the backdrop of the alliance forged between the ruling family of the Sauds and the clerics owing allegiance to Wahabism, an orthodox brand of Islam, decades ago. The alliance was aimed at granting legitimacy to the rule of Sauds. In the 1990s, though, powerful Wahabi clerics criticised the ruling family’s attempt at reforms. Some were imprisoned, yet their opposition slowed down the reforms the royal family had envisaged.

Kuwaitis demand the PM’s resignation. (Photograph by AFP, From Outlook, March 21, 2011)

The complex relations between the king and the clergy occasionally blurs the real target of protests. In November 1990, for instance, a group of 47 Saudi women got into 15 cars and drove around the streets of Riyadh. The act predictably outraged the Saudi society, especially the powerful clergy. Fawziah Bakr Al-Bakr, a leading member of the 1990 group, told Outlook, “I barely drove around for half an hour but I was banned from working in Saudi Arabia for three years.” Now teaching in the King Saud University, she says women here want to be recognised as full citizens of the country. This means Saudi Arabia will have to lay down the age of consent for women, in the absence of which they are perpetually dependent on their male guardians.

People here say the reigning monarch, King Abdullah, favours reforms, particularly for women. Recently, he courted criticism from some sections of the clergy when he allowed men and women to work together at the King Abdullah University in Riyadh. His daughter, Princess Adila, has been insisting that Saudi Arabia won’t progress unless women enjoy equality with men. The question is: will such changes be acceptable to the clergy and the more traditional elements of society?

It’s indeed a divided society. For instance, there are sections demanding a constitutional monarchy; in opposition to them are those who want elections at various levels of government, including the Shura Council, a consultative body whose members the king nominates. Another pressure point arises from rising unemployment, said to be anywhere between 1,50,000 to 4,00,000 (including disguised unemployment), a cause of worry in a country where 70 per cent of people are below 30. They could be absorbed in the private and public sectors, but the problem is that the Saudis, irrespective of competence, want to begin at the supervisory level. In addition, corruption in providing relief work following the floods in Jeddah in 2009 has shaken people’s faith in the regime.

For long, the Saudi royal family has moved gingerly, resolving contradictions before introducing reforms in the social and political spheres. But it can’t afford the luxury of procrastinating, now that neighbouring Yemen and Bahrain are teetering on the brink. The ruling class is particularly worried about Bahrain, where the Shia-led protests could have reverberations in the bordering province of Dammam, which not only boasts of key oil installations but is home to the majority of Saudi’s Shias, who comprise about 8 per cent of the country’s 6.5 million population.

Demonstrators in Sana’a, Yemen, call for the ouster of president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

“We have to ensure peace and stability in Bahrain,” says a member of a leading Saudi think-tank in Riyadh. His colleague is more forthright: “If need be we will intervene. We will not allow a revolution to take place in Bahrain.” Such political analysts say Saudi Arabia can’t sit idle as yet another country in the region comes under Shia influence and, therefore, as implied, under Iran’s. They contend that had the Saudis been more proactive in Iraq, Baghdad couldn’t have slipped under Tehran’s sway.

The realists in Riyadh not only dismiss the possibility of their country intervening in Bahrain, they also say there is no evidence of the Iranian hand rocking Manama. They believe the Iranian bogey has been habitually raised to curb internal dissent and rally the Sunni majority behind the ruling family, which is increasingly alarmed by ominous signs. For instance, this week has witnessed demonstrations by Shias. In January, people in Jeddah demonstrated, demanding compensation for the recent floods. Recently, a group of 50 burqa-clad women staged a protest outside the interior ministry in Riyadh, demanding the release of their family members. And though the government has banned protests, some 1,00,000 people have reportedly registered for a street demonstration in Riyadh on March 11.

But imposing a ban on protests is only one of the strategies adopted to ensure Saudi Arabia bucks regional trends. Lavish sops have been offered to people, and the king has been accepting petitions demanding reforms on issues ranging from the political to women-centric and cultural affairs. Says Talmiz Ahmad, India’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, “The kingdom is unlikely to be affected by the trend in the region, for the king is both loved and respected.” Adds a senior Saudi official, “This is a country not governed by decrees, but by consensus.” Others say that with the king being a balancing factor in a country riven with tribes, his removal might unleash a civil war. Instability is anathema to the majority who have gained from the system.

Saudi is on the cusp of witnessing radical reforms, but these, experts feel, will be at the pace the rulers are comfortable with. But then, such views could go awry, for revolutions overturn inherited wisdom and established premises.