For almost three decades now, politics worldwide has been defined by the legendary James Carville quote “It's the economy, stupid”. The phrase captured the idea that at the end of the day, people voted on how their country was performing economically i.e., on issues like inflation, unemployment, jobs etc. As the world rapidly globalised in the 1990s, the phrase became the default setting of global discourse; meaning elections were determined by how a nation was doing economically under the incumbent government. Even under non-democratic regimes, the economy was usually cited as the primary reason for upheaval, for example, unemployment and inflation were credited as the key reasons for the Arab Spring uprisings of the early 2010s.

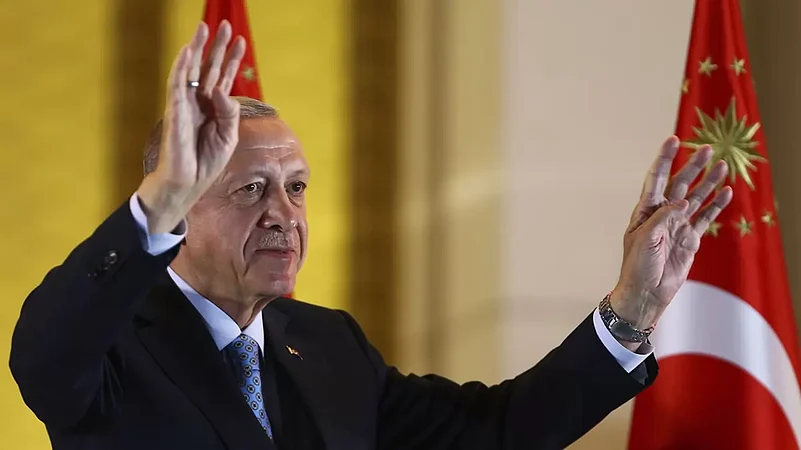

However, in May earlier this year, this concrete idea suffered a massive blow when voters in Turkey, in the face of extreme inflation credited to the government’s economic mismanagement, re-elected their much in-news strongman Recep Erdogan. Whereas several commentators decried the contest's unfair nature, Erdogan was still very popular despite everything. In fact, for some time now the world has been seeing a slow movement away from the economy being the bedrock of elections. For example in the 2020 Sri Lankan parliamentary elections, people chose to vote for Mahinda Rajapaksa’s party even though the nation’s economy was facing a crisis under his brother’s tenure as the President. It isn’t as if people do not care about their economic situation anymore, it’s that in the current tense geo-political climate, voters are now also prioritising their nation’s foreign policy when they choose to rally behind a leader. Even in India, many commentators credit Narendra Modi’s foreign policy as a key reason why he dominates national polls.

Global Phenomena:

It isn’t as if this trend is exclusive to a particular bracket of nations that can be classified under a label. For instance, in Lithuania since the latter half of the last decade, foreign policy has been a crucial factor for voters, credited to the increasingly expansionist nature of Russia. Their former President Dalia Grybauskaitė had in as early as June 2018, said that Western states will "wake up" (to the threat posed by Russia) only "when they have been attacked" by it. On the other hand, even a monarchy like UAE has shown greater interest in having a more independent foreign policy, first by becoming one of the first few Arab states to have a normalised relationship with Israel and then signing into the much-discussed I2U2 quad. UAE has also been credited with trying to be a peace broker across the region, having successfully initiated a mediation effort between Ethiopia and Sudan in 2021 and also achieved something similar during the recent Sudanese crisis.

Who?

This is one of the rare cases where before the why is unpacked it’s important to understand who are the stakeholders in this exercise. The nations where foreign policy is a domestic issue can be classified into four groupings:

Identity: These are nations that believe they have been neglected in international forums and want their voice heard. They seek to bring light to their concerns which they believe aren’t being addressed in the current order. Nations like these tend to have a domestic narrative centred around bringing a new set of opinions to the table. For example, India which at points has claimed to be the voice of the global South and domestically speaks of being a Vishwa Guru (teacher to the world). Another example of a country trying to get its voice across is the South American giant Brazil. The nation, like India, has maintained strategic autonomy in the face of the Russia-Ukraine crisis. Commentators had expected a government change earlier this year, would also result in a more pro-western approach by the nation but that hasn’t happened, indicating the nation wants to secure its national interest above all.

Opportunity: This is found among nations whose people are confident that they can exploit the new great power game. The best example of it would be Qatar, a country whose foreign policy tightrope walk is considered a master class in diplomacy by many. Singapore is another example of such a nation. There aren’t many democratic examples of such nations, largely cause these decisions need to be long-term oriented which isn’t something nations which regularly face elections can afford to have.

Insecurity: Security is a fundamental reason why nations tend to collectively start looking at foreign policy. As mentioned earlier, Lithuania is a wonderful example but the best case to look at is Taiwan. For the last two terms, Tsai Ing-wen has won presidential elections largely on the back of having a strong command over her foreign policy. Her ability to induce security amongst her people is a key factor behind her electoral success. Another example is Israel where Benjamin Netanyahu has managed to keep his hold over power exclusively because of his hawkish foreign policy.

Change: These nations are the ones primarily responsible for driving foreign policy to the limelight. Their citizens believe there needs to be a radical change in the global order. Low-hanging fruits here are China and Russia but they are not the only ones. There are middle powers like Turkey, which have expressed their desire to play a greater role in world affairs, calling itself the conscious of the world.

Why now?

A brief look at the stakeholders explains the why part to a great extent, what it doesn’t explain is why is it happening now. So, why did things take such a dramatic turn in the latter half of the last decade? A simpleton argument would be that the rise of China has created that space but that doesn’t explain the ambitious approach of middle powers and hyperactivity amongst smaller nations. To understand that one needs to go back to the 2016 American presidential election.

One of the key campaign points of Donald Trump's 2016 presidential win was his rallying against globalisation and how the world was profiting off America’s hard work. His stirring slogan ‘America first’ was a departure from a decades-long consensus of American administration assuring a global order policed by Washington. Trump kept true to his words and proceeded to start a trade war and started disengaging with long-standing NATO allies. This was followed by deep demonisation of China and anyone who didn’t follow American diktats, as a threat. This in turn created the space and environment required for politicians (democratically elected or otherwise) across the world to create pro-nationalist narratives.

Joe Biden did promise to reverse this trend if he was elected and to a certain extent he did. But he has, despite criticism, continued to push an America First policy. In fact, he has upped the ante when it comes to China, going ahead and creating a military alliance in the Indo-pacific (AUKUS) and taking a hardline stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

That’s why despite a move away from authoritarianism in the past few years, with the likes of Bolosanaro losing, the world hasn’t seen nationalism decline. Thus, fuelling more curiosity of the masses towards the foreign policy of their country ensuring it becomes an electoral issue.

(Paarth Pande is a freelance journalist and political commentator.)