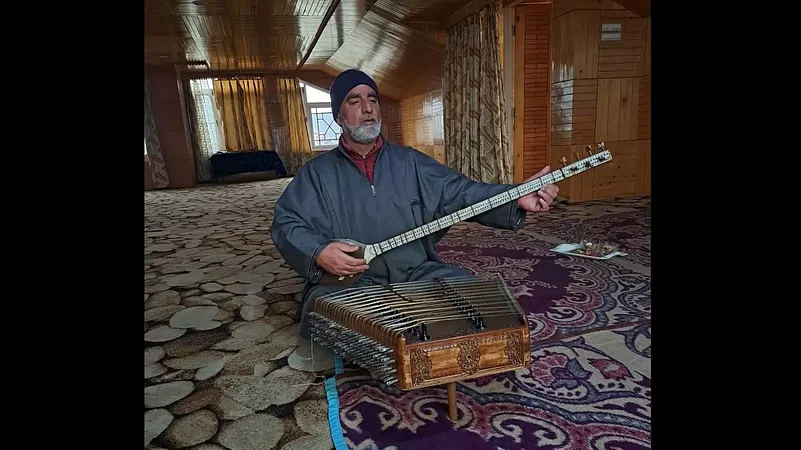

With Santoor in front of him, Ustad Mohammad Yaqub Sheikh is playing Kashmiri sitar by holding the instrument in his lap. He is singing Persian Sufi poetry in a Kashmiri accent by slowly raising his voice in tone with music.

Sheikh believes voice and music in any Sufi singing move together, bringing a person closer to the divine. As he places the instrument on his right side and starts talking, one of the last classical Sufi singers of Kashmir sounds hopeless about its revival.

He expresses his anguish over the way Sufi music is being treated in Kashmir with new “Sufi singers” emerging from everywhere and describing everything as “Sufi music”. “Even some are beating drums in these Sufi songs,” Sheikh says dismissive of these Sufi singers accusing them of turning pure Sufi Music into pop.

For Kashmiri Sufi Music essential elements are Santoor, Kashmiri Sitar, Saazi-Kashmir, Rabab, Sanrangi, Nutt, and Tabla and most of its songs are in Persian.

Sitting in his home on the outskirts of Srinagar’s Mochwa area, Yaqub has grown up with Sufi Music and has all along remained with the great Sufi singers of Kashmir in Srinagar’s downtown.

He was the first Sufi Singer of Kashmir who trained a number of girls at his home. “I taught Sufi music to girls. We have a long tradition of Sufi poetry with Lal Ded as the leading light. I thought why not teach the girls this divine music? And funny and tragic request I got from some people who consider themselves connoisseurs of Kashmiri music and Kashmiri Sufi Music was that I should allow these girls to sing in marriage functions,” he says.

Such suggestions and such an approach toward Sufi singing have broken his heart. Sufi Music, Sheikh says, is a divine experience and Sufi mehfils (functions) are traditionally held during the night. “And we know what happens in a marriage where even traditional Kashmiri folk singers are told to sing Bollywood music after some time in these functions,” he adds.

Sufi music has 12 Muqams (the spiritual stage that marks the long path followed by Sufi singers leading to the vision of and union with the divine) and all Muqams have Persian names like Buzrag, Araq, Ushaq, Nawah, Asfahan, Zir-Afghan, Rahavi, Hijaz and others. However, Sheikh says, Kashmiri Sufi singers have given a Kashmiri touch to Persian Sufi poetry. He has also rediscovered many other Muaqaams like Nowrozi Ajam, NoroziArab, Behbas, and Ramkalai.

Sheikh’s grandfather late Ustad Ghulam Mohammad Qaleenbaft is considered a doyen of Sufi Music in Kashmir valley.

Sheikh learned music from his grandfather. Like his grandfather Ustadd Qaleenbaft, Sheikh also started from Radio Kashmir Srinagar as a Sufiyana staff artist. He retired in April 2020. However, while in service, he came up with Qaalenbaft Memorial Sufiyana Music Institute.

“I realized these days young educated boys and girls are interested in Sufiyana music. So through notations, I would make them understand its nuances and the students would learn fast,” he says. In his institute located on the third storey of his house, he would train those youngsters passionate about Sufiyana. “I think I really brought a revolution in Sufi Music when I motivated young educated girls to learn Sufiyana music,” Sheikh says proudly.

The girls did exceptionally well and they travelled across India performing Sufiyana Music. This was seen as unusual practice. Earlier Sufiyana Music was confined to certain families and it would revolve around them. But Sheikh is credited with taking the music to anyone interested to learn without charging anything. Since 1998, he has trained 80 youngsters including 20 girls.

“The problem is that music requires your time and we live in times when trained Sufiyan Music artists don’t have avenues to earn. There are the government posts available in the different departments but they no longer do such recruitments and hence youngsters go to different streams and leave the music halfway,” he adds.

“My father was a contractor. He was the devotee of my singing and he would always insist that I should sing. I was reluctant to sing before my parents. Whenever I would sing it would turn my mother unconscious as she understood Sufiyana music and its meaning. That is why I was reluctant to sing before my parents,” he adds.

Ustad Yaqub has devoted his life to music. He has been in Europe and in African countries and has performed Kashmiri Sufiyana there. “I remember our Sufiyana was venerated because of quality. It is a music based on principles, based on a particular system and order. It is our classical music. It needs to be preserved with its originality intact,” he adds.