God is a falling leaf

God is a snail shredding God into smaller pieces

God is fungi further breaking God down

God is nitrogen and other nutrients

God is fertile ground

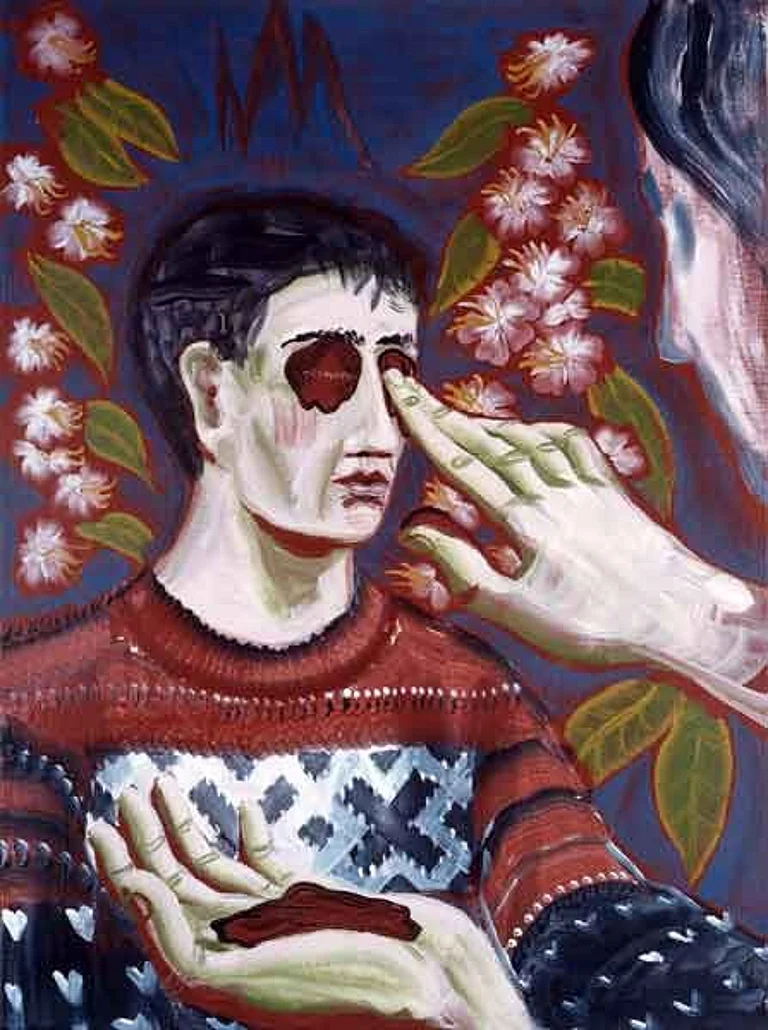

Ecology is the study of relationships between living organisms and the environment. This is a specific discipline in science, of course. For me, this is also a spiritual and poetic practice: to study the relationships that we take part in and that we can become aware of around us. There is a falling leaf. What happens to this leaf? Death is relative. The leaf is part of a larger ecosystem. And I claim God is not different from this. It's not God's leaf. God is that leaf.

A split that is quite typical in many cultures is to see ourselves, us humans, as separate from nature. We also do that in spirituality and religion. According to many if not most traditions, humans and the divine are somehow different and above nature, and liberation means transcendence. In contrast, The Garden Tantra (Red River, 2023), my latest book of poems, is influenced by tantric, bhakti and zen practices where the here and now is the focus, where it's not about leaving this material, embodied existence. To use the common spatial metaphor, God may be above and we need to rise, but certainly also ‘God is fertile ground’. In ‘Locating Souls’, I write:

Perhaps there is not a soul

in the brain. Perhaps in the heart.

One place is certain.

Remove your shoes and be aware

here where the pressure is high

yet you remain so very sensitive,

here where you find the grassy, gritty origins

of humility and humanity.

Vira Vikram knows. Only those who are still lost

discriminate between high and low.

In ‘A mirror’ I invite the reader to close their eyes and look deeper at who/what/how we are. When I write about different elements, air for example, I write the air that makes up you and / other animals and plants. I am including humans in the wider family of animals and plants. We are animals and we are also very related to plants. Furthermore, I don't separate between what we typically think of as living and not living beings. For example, I write the minerals that make up you and / other grains of sand, mountains and rock planets. We are also very deeply related. In a sense, the entire universe is needed for us to exist. In tantra and zen, we also say that the entire universe is present inside us, the microcosm. Continuing with spatial metaphors, God is within.

There is a Kabir poem about a garden. In Tagore’s translation, it goes like this:

Do not go to the garden of flowers!

O Friend ! go not there;

In your body is the garden of flowers.

Take your seat on the thousand petals of the lotus, and there gaze on the Infinite Beauty.

I agree that going within is very important, but we can also get lost as we take that way. It’s important to not dismiss the reality of relationships and our surroundings. We are related to everything, and there is great variety in this universe; just enough separation to enjoy the other, as other bhakti poets say. In the opening title poem, ‘The Garden Tantra’, I go out into a physical garden. And I am affected by this physical garden. I don't attain peace by just focusing internally. No, I lose my hard frown / somewhere among the wildflowers. Just spending time outside in natural surroundings has a very important healing effect on our bodies and minds, something I also know and use as a therapist. If we can be outside with awareness, it has an even stronger effect on us. And it's reciprocal. When we spend time outside in our natural surroundings and are healed, we also want to take care of our natural surroundings. There is a falling in love again with the natural surroundings, a bhakti for God as a wildflower.

An important realisation one can get through zen and other Buddhist practices is that there is no independent inherent self. Everything is radically related and interdependent, whether we think so or not. One poem’s title comfortingly tells you ‘You’re not selfish’:

Though you think much of the time

along lines of I, me, mine,

though you feel apart

from grass and pine,

you’re also a part

of a whole

or even more

interpenetrated:

without any effortful will,

just standing still in this garden,

you constantly feed

the sturdy pine facing you,

and the delicate leaves of grass

crowding your feet,

and they feed you—

breathing in, breathing out.

Having done breathing meditation for a while or through just this one breath you take now, you can spontaneously realise how intimately linked everything is. We are fed air by the grass, by the pine and everything else around us. And we actually feed the pine and the grass with our outbreath. That exchange is constantly there, without any effortful will, without you having to figure something out in your mind. Just relax for a moment, the fact that you're breathing is already a participation in the whole. In a sense, you cannot be selfish. In our thinking mind, we may struggle and judge ourselves and others as being too selfish, that we should be doing this or that. This also happens in environmentalism. I don't think this kind of thinking is where we find the answers to what we should be doing. As a therapist, I know how many of us get fixated and stagnate in a kind of topdog-underdog dynamic intra- and interpersonally, the topdog shoulding all over the underdog and the underdog having its tricks and excuses. We can overflow and act from another place when we feel full. And I hope this poem helps fill us up a little bit.

Just to be clear, I too can feel great despair and grief and hopelessness with regards to our current ecological crises. We are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction on Earth, and the causes are all human-related. So what to do? When my husband and I first got a garden, I tried to prevent cats from coming and killing the birds here. Cats along with other domesticated animals are a great threat to many species, including birds. I started peeing around the perimeter and putting out used coffee beans, which cats apparently don't like. And yet, in the poem ‘In the midst of an extinction event’, a cat startles me (or the poet speaker) as I sit reading and writing in the garden. The cat comes closer and closer as the poem progresses:

She strides across volumes

one and two of selected poems by

Mary Oliver, sniffs the empty cup

of coffee and rubs up against bare legs.

The human has been marked. Now he offers

a hand, the hand he used to lift the ant.

The cat thrusts herself, head first, into it.

The cat fills the open hand. ‘So much fur,

it must be hot for you,’ the human says.

The cat slowly blinks. The human continues,

‘Have we met here, before the coffee beans?

Did you think I’d appreciate the bird?

Please do not thank me like that again, though.’

The human croons, the cat purrs and purrs.

Then the cat curls up in the human’s shade,

and the human returns to our poem.

This poem offers no obvious solution to the mass extinction event we find ourselves in. But there is a developing relationship between this human and the cat. There is some empathy and kindness. Regardless of what we do, I am a strong believer that the means must reflect the end, I believe in awareness and kindness.

I started out by saying that we make splits between nature and the human, nature and the divine. The written word, conceptual thinking, and language more generally can contribute to this. And poetry is very much about language, of course. But language is not just meaning, it is also sounds, sounds just like sounds we find in our natural surroundings. And it is breath and air. ‘How a Poem Is Made This Summer Morning’ lists several ingredients, including the crisp morning air on this face, the abrupt clap of a pigeon, coffee, and much more, and ends with

the alphabet, the m still like a wave from the water letter mem;

the entire universe nurturing what I normally think of as me

makes a poem.

M comes from the Hebrew letter ‘mem’ which was related to water. If we look at the m, it looks like a wave, right? We humans are still mostly water, and we can never really leave our true nature behind.

Vikram Kolmannskog is a writer and professor of gestalt psychotherapy.