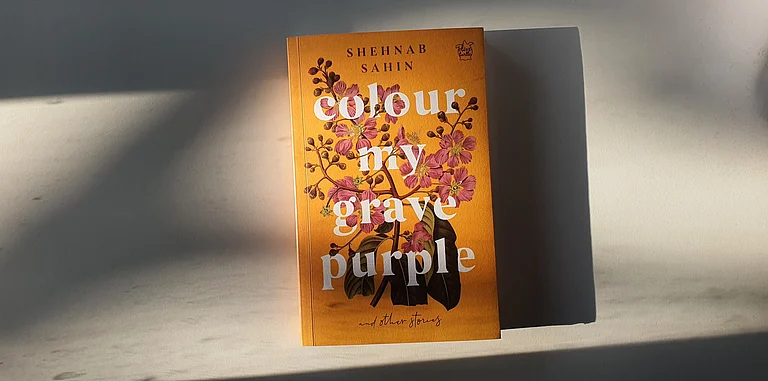

The Goncourt Prize, France’s most prestigious literary award, was set up in 1862. In 2024, for the third consecutive year, students of French from all across India participated in the ‘International Goncourt Prize—India’s Choice’ programme run by the Académie Goncourt. The Indian jury was composed of students from eight Indian universities and students from the network of Alliances Françaises. They declared Neige Sinno’s Triste Tigre winner of the Goncourt Prize—India’s Choice. Praising the book, the jury said, “Triste Tigre poses profound intellectual inquiries without offering simplistic solutions...Sinno astutely observes that silence isn't merely a consequence but a fundamental aspect of the aggression itself in cases of violence. Thus, breaking the taboo surrounding discussions on incest in society becomes imperative. [The book] serves as a clarion call, urging us to break the silence and strive for a more just and compassionate world.”

Published in French by P.O.L in September 2023, Triste Tigre became a literary phenomenon in France upon its release. It is currently being translated into English by the American publishing house Seven Stories Press, also the publisher of Nobel Prize winner Annie Ernaux. In Triste Tigre, Sinno draws on her personal history—her stepfather sexually abused her from ages 7 to 14—and the ensuing trauma she, her family, and friends had to grapple with. Her book also dives into works by other writers in search of similar themes and draws inspiration from authors such as Virginia Woolf, William Blake, Mary Gaitskill, and Toni Morrison who shine a light on experiences that “aim to annihilate the other, to deny his/her humanity”.

Vineetha Mokkil spoke to Neige Sinno. Excerpts from the chat.

Congratulations on winning the Goncourt Prize—India’s Choice! When did you decide to start working on your book?

Thank you so much. Starting this book was not a conscious decision. I began to write a piece without realising at first what it was, and when I saw that there was an interesting voice and form in it, I had the feeling of having stumbled on something important (for me). Something that could lead me to a book I had postponed for years. This had to do with the fact that I didn’t want to write an autobiographical account of my experience in the form of a traditional memoir. I think of Triste Tigre as creative non-fiction, which is a vague label...For me, it means that it was written with the techniques and tools of fiction, but the material is not fictional.

It is very difficult to write about deeply personal experiences—especially incest and sexual abuse. How did you navigate this challenge?

It was difficult indeed, and challenging in a positive way. It brought an intensity to the writing. To keep walking on the border between subjectivity and objectivity is a very specific challenge of this book. It gives the book its fragility and beauty but it also shows the limits of such an approach. I couldn’t stand to tell that story only as a personal tragedy, but I didn’t want to talk about rape as an abstract matter either. This movement that goes back and forth between my personal experience, the experience of others, and the social problem of child abuse gives the text its particular rhythm and strength.

How has the process of sharing your personal life experience with readers affected you?

What is strange about the experience of abuse is that it is at the same time deeply personal—it affects you in so many ways that it seems almost impossible to share it—and a very common experience. Child abuse, sexual abuse—these things happen everywhere all the time. We all know people who have been victims of abuse. But it is silenced; it causes pain and shame to those who dare to talk about it. The fact that a door seems to be opening now, that many sections of society show signs that we are ready to hear about that reality and want to do something about it is giving me a lot of hope.

Your book has received high praise from both readers and critics. Were you ever nervous about the kind of response it would get?

I had no idea that this would happen. It was hard to find a publisher in the first place and I almost lost faith in the possibility to publish the book, so the prizes and extremely enthusiastic reception were a surprise. It doesn’t mean I wasn’t confident about the book itself. I know it is a powerful book, I can feel its energy and I saw how my friends reacted to it when they first read it. I am grateful to my editor who was courageous enough to overcome the fear to publish it, and to all the readers who did the same to accompany me in my quest.

Which writers gave you the courage to take up this project?

I think the experience of being a reader for many years builds up a complex universe of references and it is not always the most obvious reference that actually helps. There was a lot of resistance in me to jump from fiction to non-fiction. Seeing that writers I admire did it in very interesting manners was an important motivation. For example, I can mention Dennis Johnson, William Vollmann, David Foster Wallace, Emmanuel Carrère, and Carmen Machado. One of the voices that drives the book is my voice as a reader, it is a happy and playful voice that brings in some light because it finds solace in the dialogue with many texts and authors. Some authors are directly brought into the text in quotations, but others are simply protective presences, or hidden references. This helped me to feel less alone in the strange adventure writing this book has been.

Incest is still a taboo subject in many societies (including India). Can books like Triste Tigre give people courage to speak up?

The question about the taboo is not so much that victims don’t talk; it’s more that no one can hear what they have to say. We don’t want to hear those stories. We’d rather say that it’s awful and think about something else instead of exploring what it really means that children are abused in so many families. People open up and talk about it when they can, I don’t think a book can directly trigger that. But literature can change the way we receive the stories, it changes our way of reading, interpreting, and informs our perception and judgement. In that way, it participates in social change, giving a voice and a form to questions that are too vague and strange to be formulated in ordinary conversations. Suddenly we start seeing things in a new light and things that have remained unsaid, unthought, and forbidden become available to language and thought.