At the Tata-Corus press briefing in London, Ratan Tata, chairman, Tata group, was hounded by photographers. "You don't want to photograph me where I'm going," he joked as he stepped into the toilet. But increasingly, Indians are stepping out of their protective environment and scouting for acquisitions abroad. More importantly, Indian businessmen, who were till recently interested in smaller markets like Africa and Asia, are flexing their muscles in mature and developed ones (see chart). The Tata group, whose Corus deal was the largest by an Indian group, inked 14 others worth nearly $1.5 billion in 2005-06. Others like Suzlon Energy, Videocon group, M&M, Ranbaxy Labs and the AV Birla group have also invested huge sums. According to consultancy firm Grant Thornton, while Indian firms spent $4.3 billion in 2005 on outbound (overseas) deals, the figure has already crossed the $15 billion mark in this calendar year. The average deal size has zoomed from $31.61 million in 2005 to over $100 million this year.

Globally, the image of Indian industrialists has changed.

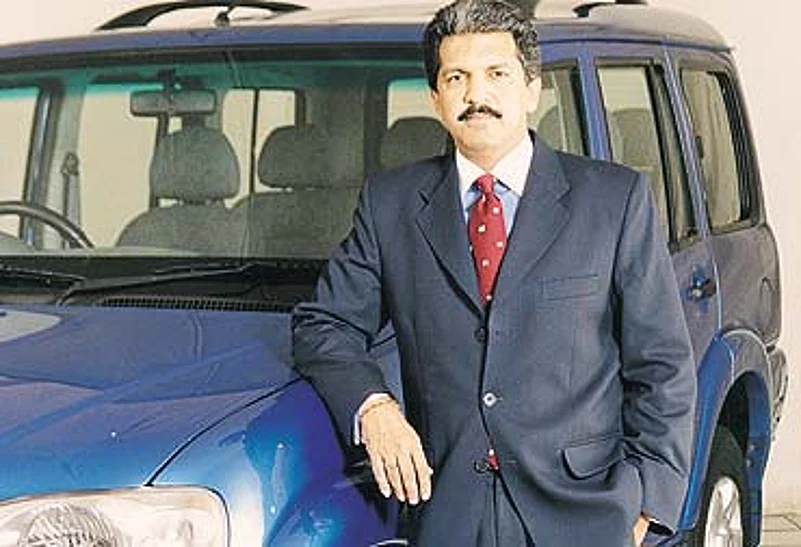

Anand Mahindra, CMD, M&M: He just purchased a German company, and plans to buy another one. The idea: earn most of the group’s revenues from either exports or overseas operations. Although his father, Keshub, was against reforms initially, Anand has realised that M&M has to become a global player.

A recent report by Boston Consulting Group (May 2006) argued that "a revolution in global business is under way," and that companies based in rapidly developing economies (RDES) like India, China, Brazil and Russia "are expanding overseas and will radically transform industries and markets around the world". It identified 100 new global challengers in these RDES, which included 21 Indian companies (like Bharat Forge, Hindalco, M&M, Tata Steel and Videocon). Last year a McKinsey study found that "emerging markets...actually provide an invaluable springboard" for companies to go global. It added that "emerging markets are seedbeds for distinctive capabilities" that enable local firms to succeed globally. In a sense, the future belongs to emerging corporate giants from these economies.

After the Tata-Corus deal, which made Tata Steel the fifth largest steel-maker in the world, a similar confidence is reflected in the attitude of Indian businessmen. Admits Subhash Menon, chairman, Subex Sytems, which purchased the UK-based Azure Solutions for $140 million, "After the deal, a couple of investment bankers and advisors, who had not taken me seriously earlier, are knocking at my door with two proposals a day." Adds Venugopal Dhoot, chairman, Videocon Industries, which took over the South Korean Daewoo Electronics and the French Thomson for a combined $1 billion in two separate deals, "There's a huge craze and curiosity about India and Indian companies. So, this is a good time to acquire foreign firms." A 2006 study by mape, an investment bank, noted that "the Indian MNC has finally come of age. Suddenly, Indian buyers have become a force to reckon with in many industries such as pharma, auto components and oil/gas."

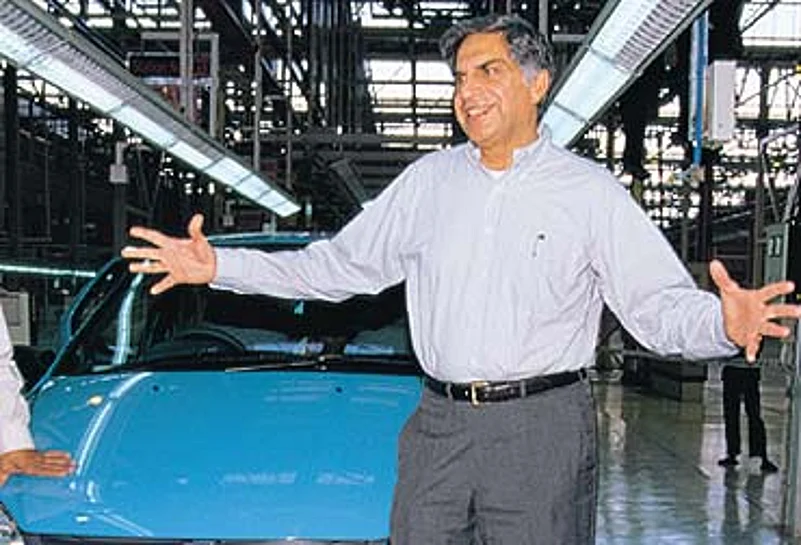

The Indian promoter is ready to execute the deal of his lifetime. He's waiting for, as Ratan Tata puts it, "the defining moment" that'll catapult him into the big league.

Kumar Mangalam Birla, MD, AV Birla Group: He has always been involved in M&As and restructuring. After consolidating the domestic operations within the group, he’s now looking to buy global firms. The recent buyout of the Canadian Minacs was the step in the right direction.

Fortunately, there are many opportunities to further such ambitions. Globalisation, which proved to be the bane of Indian managements in the 1990s, is impacting the Europeans and the Americans. Thanks to the benefits of outsourcing, operations in the developed economies are more expensive and hence, unviable, compared to the units in India or China. For example, the production costs at Corus' Port Talbot plant is twice that of Tata Steel's Jamshedpur unit. To survive, Corus had to either close down its plants in Europe and shift production to low-cost bases. Or cash out, which it did. Such firms have to react with passion, and as Corus chairman Jim Leng said, "with commercial passion."

This implies that many of them will be more than willing to sell out. Today, they get attractive offers because commodity prices are still riding on an upward crest despite the correction in May this year. Explains Aditya Sanghi, country head-investment banking, Yes Bank: "European firms have been slower at adapting to India and China, both in terms of the latter's low-cost production model as well as thinking of them as markets." They have also been unwilling to change, either because of management lethargy, strict regulations, strong trade unions, or nationalistic sentiments. It's a perfect setting for Indian firms which, says Frank Hancock ofABN Amro, "are both low cost and high skill, a unique combination."

Instantly, it gives them global scale, a portfolio of recognised brands and access to huge markets. Listen to Dhoot, who feels that size matters. "Our presence is now well-acknowledged because we have acquired companies that have their footprints across the world. In colour picture tubes, we have a fifth of the global marketshare and we're talking to LG-Philips to take over their picture tube operations. We're aggressively looking at the acquisition route and will follow it as our growth strategy," explains the Videocon chairman, who aims to nearly double his group's turnover to $10 billion in the next few years.

Malvinder Singh, CEO, Ranbaxy: He has realised that global acquisitions will help position his firm in new markets, and make it a global player. Already, Ranbaxy has eight overseas plants, and 80% of its revenues comes from those units. What it learnt in the Indian market helped Ranbaxy become a major generics player.

Malvinder Singh, CMD, Ranbaxy, feels the same. "Overseas forays are meant to position yourself in new markets. There's a growing realisation that we've no option but to go global," he says. Ranbaxy has manufacturing bases in eight countries, and derives 80 per cent of its revenues from overeas units. Adds kpmg's Rohit Kapur, "The investments that Indian companies have made overseas were essential for them to become competitive on a global basis and increase visibility with customers." And G.V. Prasad, vice-chairman and CEO, Dr Reddy's Lab, which purchased German generics maker Betapharm for Euro 480 million, thinks the Indian market is not enough to "sustain our growth momentum."

A combination of reasons were responsible for Godrej Consumer Products' acquisition of Keyline, one of UK's leadingFMCG firms. "Keyline has a strong portfolio of brands and a well-developed customers' base in numerous supermarket chains. Market access too was critical as the size of the UK market for hair colours, which contributes to 35 per cent of our turnover and 65 per cent of profits, is five times that of India," says Hoshi Press, executive director, Godrej Consumer Products. In fact, Godrej plans to shift some of Keyline's operations to India, where costs are 30-40 per cent lower than the UK. "Indian firms are following the model developed by the Japanese when they were playing the catch-up game with the West in the '70s and the '80s," says Joel Ruet of the London School of Economics.

What's aiding Indian businesses are the lessons they've learnt in the domestic market, and easy—almost unending—access to capital to finance the big buyouts. The McKinsey study pinpoints the advantages of the Indian experience. Ranbaxy earlier operated "under a unique patent regime that encouraged Indian companies to manufacture patent-protected drugs and make them affordable.... Thanks to that experience, Ranbaxy succeeded in becoming a leading generics producer in both the US and Europe." Asian Paints, which has a sizeable global presence, "had already reduced its working capital turns to levels below those of all but one of the world's leading paint companies...."

In some cases, the Indian market provides a cushion against takeover blunders. "Our domestic market is growing so strongly that it provides us with a safety net to look abroad. We can, therefore, take such risks and they can be sustainable because of our strengths in the Indian market," contends Tulsi Tanti, CMD, Suzlon Energy, which bought Hansen Transmissions this year. In Tanti's case, Hansen's takeover was technology-driven, as the Belgian firm was the second-largest manufactures of gearboxes, a critical component for Suzlon's turbines.

Tulsi Tanti, CMD, Suzlon Energy: He feels a strong domestic market gives a safety net for a sustainable strategy to look outwards. He bought the Belgian Hansen Transmissions because of technology-related synergies. After all, Hansen is the second-largest maker of gearboxes, a critical component for Suzlon’s turbines.

Obviously, it helps if you have money in your pocket, or banks are willing to lend huge sums to you. "There's abundant liquidity in the world today, and India and China are among the main beneficiaries of this boom cycle. Indians can now borrow in the international markets, and these have increased by 91 per cent in the second quarter of 2006," reveals Jean-Joseph Boillot, a French economist who's written a book on India. Adds Ranbaxy's Malvidner Singh: "Due to increased availability of capital and excellent financial performances by Indian firms, it's easier to access capital."

But that can also lead to crucial and debilitating mistakes. Boillot feels that several mergers can go wrong and, in fact, the "success rate of cross-border m&as is abysmally low and less than a third add value to the acquiring company." The reason: overestimation of the merger benefits and, hence, overpaying for the target company. Critics like Saikat Chaudhari of the Wharton School feel that the purchase price in the case of Tata-Corus deal was "on the higher side" (see interview on page 42). Sudip Nandy, chief strategy officer, Wipro Technologies, which has made several smaller m&as, thinks that "acquisitions are basically disruptive events which stall the business momentum. "

What Nandy is referring to is the difficult integration process between differing management mindsets, stark cultural differences, and out-of-sync operational processes. "We have identified human resources, deriving value through organisational structures and navigating complex labour laws as the key challenges in any integration process," explains Mohit Rana, principal, AT Kearney. Adds Harish H.V., partner (corporate finance), Grant Thornton: "Acquired firms could find it hard to accept Indian managers. Indian managers will find it hard to manage businesses across time-zones and cultures."

But Indian promoters are confident of making their m&as work. Ratan Tata feels there's potential for significant synergies after the Corus acquisition. Anand Mahindra of M&M, which bought over a German company and plans to buy another, thinks his group has the management bandwidth to make such m&as work. Kumar Mangalam Birla of the AV Birla group has made several takeovers without facing too many problems. And the Tata-Corus takeover may prove to be the turning point. This will encourage other Indian CEOs to aspire to be global leaders. It is just the beginning of the buying binge.