Here are some stats to back such assertions. KSA Technopak, which estimated the average annual expenditure (on all categories including essential ones) of an Indian household at Rs 1.22 lakh, found that "spending on discretionary items (unlike basic necessities like food and clothing) grew at an average of 9 per cent per year" between 1999 and 2003. But the growth rate has spurted recently, touching 16 per cent in 2003, and probably higher in the past two years. NCAER has predicted that between 2001-02 and 2009-10, penetration levels will treble for cars, grow two-and-a-half times for refrigerators, and more than double for ACs.

Importantly, there's been a dramatic change in spending patterns. "The Indian consumer's basket, where seven categories contributed to 80 per cent of the spending in the '90s, now has 20 categories accounting for a similar spend. This implies that a consumer is spending on a wider categories of products and is increasingly making trade-offs between expenditure on essentials like food and grocery and lifestyle items," says Reddy. In a 2006 survey, KSA Technopak found that 52 per cent of urban consumers opt for branded commodities (staples and spices), and two-thirds purchase branded apparel.

Before we venture into the minds and souls of the new spenderati, let's add a few caveats. We're not saying that the entire 250-300 million middle class is on a buying binge. This segment is still small—possibly several millions living in urban areas—and comprise people who have taken advantage of the new opportunities that have opened up in the wake of economic reforms. Even today, the average spending on items like food and grocery, rents and utilities, education and transport comprises nearly 62 per cent of the overall expenditure. "The magnitude of the apportioned shares indicates the every day living costs of Indian consumers are still very high," says KSA Technopak's 2006 report on spending. Adds Reddy, "The average Indian consumer is still a cautious and judicious spender."

However, increasing numbers are joining the new spenderati. But don't mistake them for self-obsessed shoppers or materialistic maniacs. They're smart and suave. They're ambitious and confident. They believe in themselves. "I don't think the (middle-class) youngsters are extravagant—they seem to have their feet firmly on the ground but don't mind having their heads up in the clouds once in a while," says Neal Avinash Daniel, a consultant in the transition team at a top bpo firm, whose parents are retired government employees, and who loves to buy branded clothes and accessories, and pubs and eats out a lot.

Meet Ramya C. who shuttles between Bangalore, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong and Singapore in her high-stressed, jet-setting job. She works hard, and plays harder. Born to a scientist father and a teacher mother, she may sound, at first glance, like a shopaholic. (She admits, she once went to the market to buy a bandaid and came back with 20 other things.) But she isn't. "My spending is based on my wants, it's like instant gratification. I earn enough to live a comfortable life and can afford things. So, why not?" she asks.

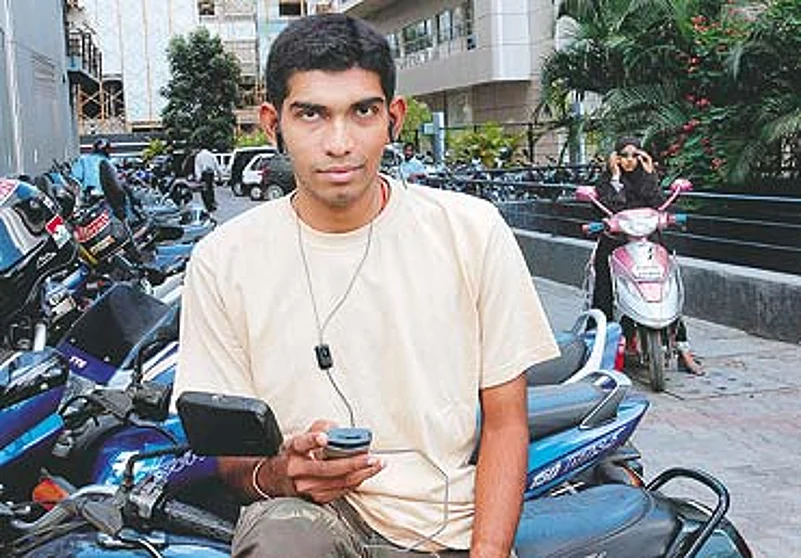

Arvind Ramakrishna, Yahoo! employee: A cellphone freak, he has changed six mobiles in six months. He wants to be up to date with technology and considers owning the latest a status symbol.

But she says she doesn't "buy everything" available in the market. Take her infatuation with mobiles—she carries three of them (an O2 mini and two Nokia communicators—9210i and 9500) and changes them every year. "Due to my work-related travel, my life depends on my mobile phones. I like multifunctional sets, which double up as a mini-office," she says. Not surprisingly, she's planning to buy a Dopod PDA phone and jokingly says that her "street value" at any given moment is "pretty high" as she carries at least two mobiles, a Sony cybershot and an iPod Nano.

For people like Ramya, and scores of others, their lifestyle is partially dictated by various choices. The first being the option to earn and spend more because of economic development, opportunities and increasing entry-level salaries (especially in services sectors like IT and BPO). Although reforms have touched only a small section of the society, today you can earn as much after two years of service as your dad did just before his retirement. Double incomes in many families add to disposable incomes. "Globally, it's observed that as the income levels rise...the proportion of income spent on lifestyle-related activities increases," says a recent ibef report. This gets accentuated due to easier access to credit and loans. The same's happening in India today.

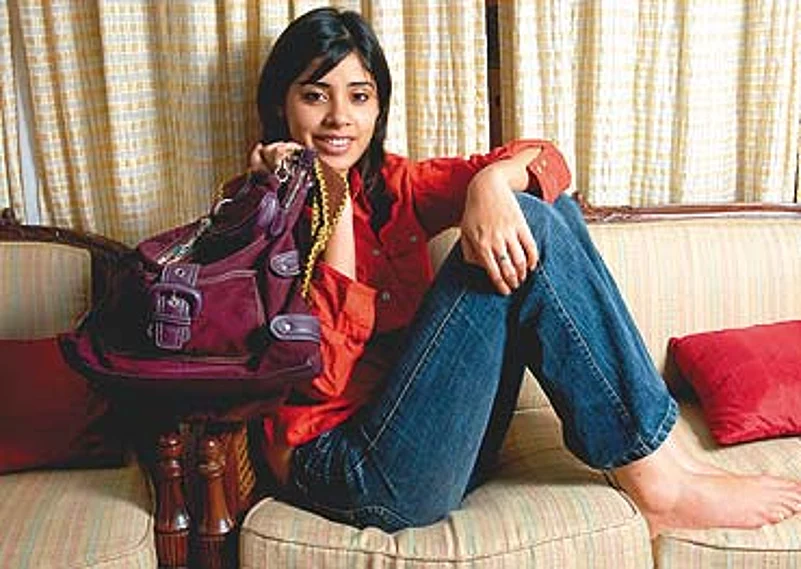

Nikita Singh, Businesswoman: Spends an average Rs 40,000 a month on conspicuous consumption items, doesn’t flinch from paying Rs 8,000 for a couple of T-shirts, parties five days a week, has taken six overseas holidays this year and does most of her apparel and accessories shopping abroad.

The second choice is the access and ability to buy all kinds of branded products in India. Earlier, one travelled to Dubai or Singapore to buy the latest; today, it's available locally. Ask the Delhi-based Nikita Singh, 27, who spends an average of Rs 40,000 a month on conspicuous consumption items, does not flinch while paying Rs 8,000 for a couple of T-shirts, parties five days a week, and has taken six overseas holidays this year (including a trip to Germany for the World Cup). "I do shop abroad because of the variety, but I also go to Mumbai to buy my clothes. There too many women in Delhi walking around in those Mango shirts. In Mumbai, I get labels like Dolce and Gabbana, Juicy Couture and Fendi," she says.

Obviously, another choice is that the new spenderati can freely—and without any inhibitions—express their individuality. They do it because they like it, they have a taste for good things, and they don't carry too heavy a responsibility baggage. As Neal puts it, there's been a shift from the family to the individual. The 26-year-old Prerna Sharma, who has a shoe fixation and owns 57 pairs, epitomises this well. Despite being a freelance interior designer without a regular income, she "earns to spend". And adds that she can't say no to "shoes that scream 'buy me'."

Similar is the case with Renu Bothra, 34, who started out as a salesgirl and now owns a clothes boutique in south Mumbai. "I spend pretty much what I earn. I don't feel guilty as it's my money I'm spending," she says. So, Renu travels abroad once a year, loves her Diesel jeans, and sports a Guess watch and Police glares. "I like to live well. I want to travel when I want to or go out when I want to, and I am willing to work hard for that."

Kamakshi Malhotra, NDTV weather girl: Lives with her parents, has no family baggage and spends most of her salary in styling her wardrobe at stores like Mango and Nine West.

For Neal, his passion for clothes and accessories is "lifestyle-related" and he admits that "being well-groomed gives me a kick". For him, to use a cliché, any compromise is death. "As we move up the career with promotions and hikes, almost without exception, we find that we can spend as much as we earn," he explains. Praveen Purushotham, a marketing manager in a US-based software firm who's into gizmos, elaborates on behalf of himself and his wife, "Our spending is based on how it fits our lifestyle, adds value to our living experience and enriches our lives in some way or the other. Personally, how much I spend and what I spend on is an expression of just being me; I spend on things that make a difference to me and my family."

Economists bracket such consumer behaviour as aspirational. "There's an aspiration to buy newer and expensive products due to increased social interaction. Many products have become status symbols for the younger generation. It's not necessity but greed that's driving these purchases," explains NCAER's Shukla. He adds that this is forcing, or pressurising, the new-gen to save less, or take loans with hidden conditions. The aspirational aspect is clear from the fact that spending in smaller towns (population: 5-10 lakh) is higher than the national indexed average, and nearly the same as the national average in others with 10-30 lakh population.

Do the spenderati feel the same way? Not at all. They say they're not proving a point to anybody. They spend because of their free will. They add that they're lucky to be in circumstances where their responsibilities are non-existent or much less than their parents. Listen to Vibha B. (name changed), who spends her entire salary. "My salary is my own, as my husband takes care of the other needs," she explains. Vibha loves branded products, and owns over 10 watches with prices ranging between Rs 7,500 and Rs 45,000.

Unlike Vibha, Kamakshi Malhotra, 23, lives with her parents, has virtually no family baggage and, therefore, spends most of her salary in styling her wardrobe. "Why not, I am not married, I don't have to look after kids, pay rent, or anything. This is the only time I can really enjoy my money as I will soon have those responsibilities," she says. Her entire salary of less than Rs 20,000 a month is spent at Mango and Nine West which, according to her, are the only stores that offer quality clothes, shoes and handbags in New Delhi.

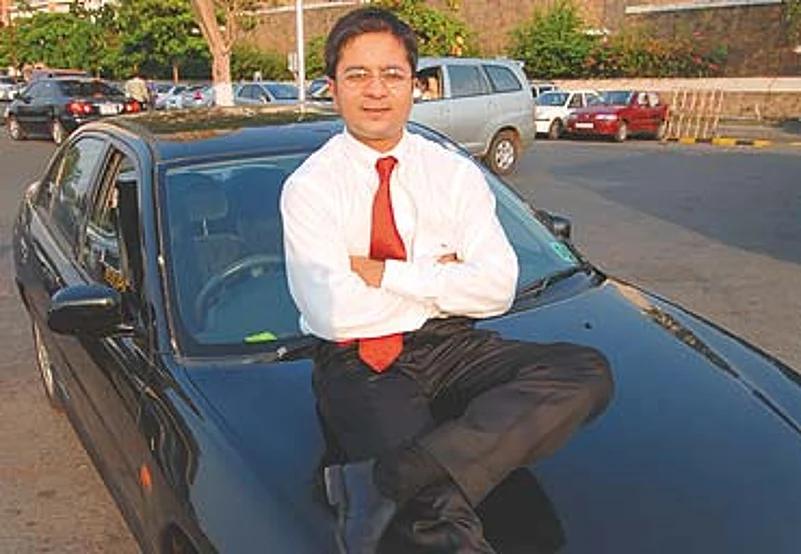

Utpal Almoula, Senior manager, E&Y : Single and unattached, he spends as he feels. He prefers big brands, has recently bought an Omega watch and owns a Lancer.

Utpal Almoula, 31, a senior manager with e&y, echoes these sentiments. He's single and unattached, and so can spend the way he feels like. He prefers brands like Hugo Boss, Ralph Lauren, Armani and Tommy Hilfiger, has recently purchased an Omega watch and owns a Lancer. "These days, our salaries are better, and we earn them younger. Because I live with my father, and I don't have to take care of the household expenses, my spending capacity is automatically greater. I don't have anyone else to spend on or save for." Even those who're married are either DINKS or DISKS and can afford to spend more.

All this doesn't mean that the new spenderati are cold and emotionless, distant from their parents, or don't have the practical sense to invest in or save for the future. Vibha buys things for her in-laws and parents, Prerna spends on her younger sister, and most are willing to take care of their parents if the need arises. For this generation, the concept of savings has changed, although the realisation to save hits them in their late 20s or 30s. "Saving for the sake of saving makes little sense. Saving with a definite end-use makes a lot of sense. And investment in any assets becomes a part of savings," explains Praveen.

Such logic makes little sense to the older middle-class generation that has grown up with a mindset that tells them to live well but within their means, and save for the future. So, the parents rarely accept what their children are doing today. But they have to realise that life has changed. Gone are the days when a family just owned a Maruti 800, if at all, had only one AC in the parents' room, and rarely went out to eat. Gone is the era when a man's favourite possessions were a boom box or an electric razor, and a woman's a blender and a hair dryer. Welcome to the 21st century period where spending is an endless, breathless urge that never seems to be spent.