- Higher foodgrain prices led farmers to increase acreage, use fallow land

- Better support services for farmers, higher use of certified seeds and fertilisers

- Favourable weather helped improve production. Monsoon to be good this year too.

- High focus on foodgrains, but, could hit crop diversification

***

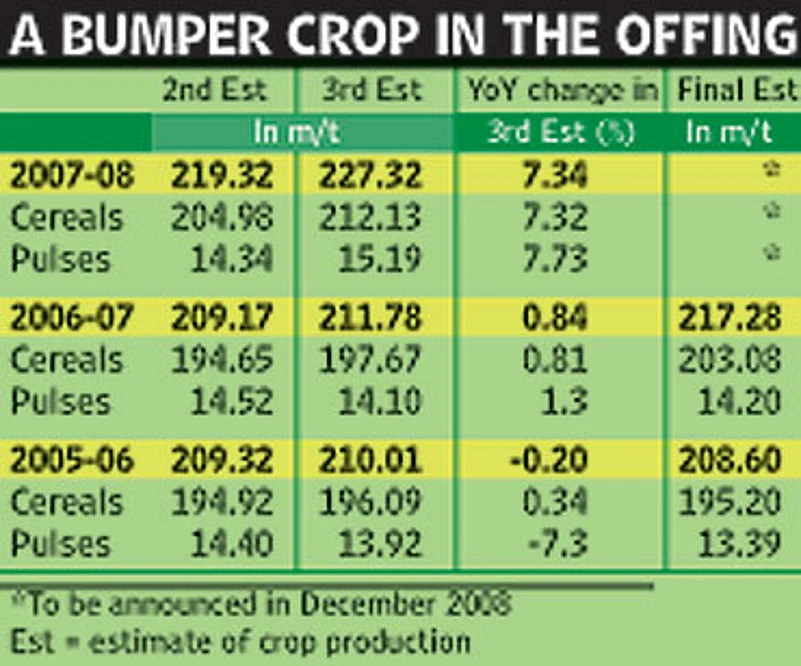

The latest numbers are indeed impressive: they reveal India has notched up highest-ever production figures for wheat, rice, coarse grains, pulses and oilseeds. In fact, the total crop estimate of 227.32 million tonnes is up by 4.4 per cent from the final tally of the previous year. These numbers, which show a staggering 7.34 per cent jump over the third estimates for the previous year, have surprised many. To put it into perspective, the growth in the third estimate in the previous two years has been 0.84 per cent and -0.20 per cent, respectively (see table). As India is a major consumer of foodgrains, the announcement had a ripple effect, cooling global markets.

So, the obvious questions are: what's behind the sudden spike in India's crop estimates? Is it being reflected in higher availability in the marketplace? And is the rise sustainable? As for the jump in the foodgrain production, the agriculture ministry attributes it to several factors—like greater government investments on improving the supply of certified seeds and ensuring higher use of fertilisers along with good monsoon and weather conditions.

All the agricultural experts Outlook spoke to agree that the numbers look genuine. "Government procurement of foodgrains is moving faster than anticipated. It shows the market is supporting this rise in food production," points out Ramesh Chand, who was a member of the steering committee on agriculture for the eleventh five-year plan.

Government procurement of foodgrains for the pds has indeed picked up. As Sanjay Kaul, director and CEO of the National Institute of Commodities Research, notes, "Government bullishness, especially in the case of wheat, seems validated by the market arrivals. There is a 30-40 per cent increase in Punjab, Haryana, western UP, Madhya Pradesh and even Bihar compared to last year." Expectations now are that the government agencies will be able to procure 17 million tonnes of wheat for buffer stocks as against a target of 15 million tonnes. Already, procurement has crossed 12.6 million tonnes against 11 million tonnes wheat procured last year—when 1.8 million tonnes of wheat was imported.

To be sure, a clearer picture of the foodgrain and total agriculture production will emerge only in July, the month that receives maximum monsoon rains. That's when the fourth estimate will be released, along with the first estimates of the next year's crop. The fifth and final tally is released only in December, preceded by the second estimate of the next crop season in September. The estimates vary greatly as there are not just two seasonal—kharif and rabi—crops to be taken into account. In some areas, there are more than two crops sown—like paddy, for instance, unlike only one winter crop of wheat. As maturing period of crops vary, the harvesting activity is staggered.

"The higher numbers are not at all surprising, given the higher acreage of sowing and higher yield in states like Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh," says S.S. Acharya, former chairman, Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices. "We seem to be on course to improve our productivity as part of measures for food security. The farmers also respond better when assured of better prices."

On the impact of the diversion of agricultural land for other uses, including setting up of special economic zones, Union agriculture secretary P.K. Misra maintains that the cultivated area remains at 141 million hectares. Chand, however, feels there's some reduction in agriculture acreage though the official statistics don't reflect it. "One reason could be diversion of land from some other usage. Even the revenue department does not reflect the true picture," he says.

Based on its data for 2004-05, agriculture ministry officials state that as much as 10-25 million hectares of land remains fallow at various times in the year. When the prices are good, as seen over the last one year, there is greater incentive to cultivate fallow land. "It's a question of straight economics. Generally 8-10 per cent of land is left fallow due to marginal economics. But if the prices of a crop go up, the farmer brings this land under cultivation," notes R.S. Seshadri of Tilda Riceland, a major rice exporter.

The production of rice, particularly highly priced basmati, is a clear case in point. As against 93.35 million tonnes rice production last year, the estimate for this year is 95.68 million tones. Similarly, coarse grains, particularly maize, have seen a huge jump given the high global prices and robust demand in domestic market from the poultry sector. Given that the government has been pushing the implementation of assured prices to farmers in just two—rice and wheat—of 25 commodities, experts warn this could soon jeopardise efforts for greater crop diversification to help farmers get better prices for their produce.

"The way wheat and rice prices are rising, we may see some switch back to growing cereals," feels Ashok Gulati, director (Asia) of International Food Policy Research Institute. "From the food security point of view this may be good, but not in terms of water stress issue. Also, two years from now, we may see a glut in cereals, but a shortage of sugar." Here's how: rice and wheat growers can hope for early and good payments after a shorter cultivation period compared to sugarcane growers. The shift may show by May-June when sowing begins.

Despite the good numbers, experts maintain much needs to be done to ensure that India's foodgrain output reaches 250 million tonnes by 2010. As the father of India's first green revolution, M.S. Swaminathan, puts it, "It is high time science and farmers got together. Our self-sufficiency (in foodgrains) is only at the current levels of consumption." The fact is that as incomes in families below the poverty line rise, it will put increased pressure on food. "A one-time good harvest does not mean agriculture is looking up. There is no real progress in investments to address issues of dry land farming," states D. Raja, national secretary of the cpi, an ally of the government.

For now, we will know the reliability of these crop estimates only by this year-end—in the past, there have been big variations. But as consumers rejoice, the ground reality doesn't change: the farm sector needs a huge policy and investment push before India can claim to have achieved consistent food security.