Although dismissed offhand as one of those ‘Southern’ frivolities—think, the much-queried ‘h’ that appends not a few ‘t’s and ‘d’s—the ‘i’ at the heart of the spelt-as-spoken biriyani is hardly superfluous. Allowances for geo-linguistic variances notwithstanding, some posit that it is a metaphor for the intensely personal relationship between sub-continental palates and the closest we have to a consensus on soul food. It’s not for nothing that biriyanis regularly pip pizzas for top spot on annual consumer food-behaviour surveys.

While this passion has long informed and whetted mostly good-natured dinner-table debates, a decidedly unsavoury manifestation has been ‘biriyani baiting’—as evinced most recently by the vitriol directed toward protestors in Shaheen Bagh, among others. To counter this appropriation, a group of cinephiles in Kerala set out in 2017 to reclaim the biriyani by adopting it as muse, motif and remuneration for their nascent production venture. In effect, turning the pièce de résistance itself into a means of resistance.

In December 2017, Biriyani Films— the banner features a steaming handi logo—released its first short, Ma(d)am, a play on the Malayalam words for religion and madness. The three-minute film has two Hindu extremists conversing about minorities and beef over a Kerala paratha and mutton meal at a roadside hotel also patronised by two Muslim men whose meal order upends their bigoted caricature.

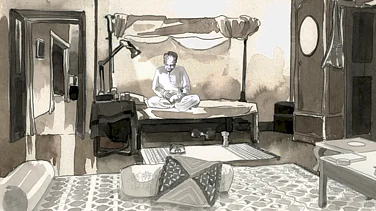

The Biriyani Films crew.

“It was a socio-political satire, reflecting on the current mood prevalent in the country,” says Parthan Mohan, the Trivandrum-based adman who co-founded Biriyani Films and directed the short. “Ma(d)am reflects an image of society that we live in and portrays a small slice of it, laced with a dash of humour.”

The humble dumpukht as agitpunkt then, but the idea too is to channel their two loves—food and cinema—to create a flavour while not eschewing meatier concerns. While there is an entire library of films—mostly out of Hyderabad—inspired by the biriyani, Biriyani Films may well be the first of a unique sub-genre that aims “to make beautiful, relevant creative content at no financial cost, but only gastronomical cost!”

“The only currency we deal in is biriyani. Right from writing sessions to pre-production, from location hunts and shoots to post-production, nobody is paid in money. Only in biriyani. You don’t get to choose your menu here either. There is no such thing as a vegetable biriyani!” Mohan says.

As to the variant of choice, he adds, “Trivians (people of Trivandrum) prefer a spicier biriyani, rich in onions and masala, with a boiled egg and accompanied by raita and pappadom(s). The Thalassery biriyani is bland for our palates. We choose the Trivandrum biriyani, which has more in common to the Thalappakatti style (translates to ‘turban’, made with jeera rice, star anise, mint and a medley of other spices) native to southern Tamil Nadu.”

Over two years and over 15 biriyanis (roughly Rs 3,000) later, Biriyani Films has been less prolific than they would like—releasing their second short Ellam Sheriyaavum (‘Everything will be alright’) about a common man’s fight against bureaucratic apathy last August. Everyone in the team works in Kerala’s film, television and advertising as also digital content creation industries in some capacity.

“There are very senior professionals and team members are humanists at heart. People who are looking for something beyond a purely monetary relationship with cinema. We haven’t had many challenges in getting like-minded people on board and the novelty of the idea was enough to spend their time for the project,” Mohan says.

The films themselves appear to have found an audience and a third film, a spoof comedy titled Shudha Jaathakam (literally, Clean Horoscope), is in the dum...er, drum. Mohan stresses that while the brand may expand into a production platform and eventually monetise their videos, its core humanist ethos will not change.

“Whenever it starts generating revenue, we hope to use the money to buy food for the needy and support charity ventures addressing hunger and poverty in our community,” he says.

By Siddharth Premkumar in Thiruvananthapuram