Chuppi hi zubaan hai. (Silence is sonorous. It has a tongue of its own.) The character of Kishorilal, a shrewd and greedy Hindu businessman, utters these words after an unusually long stretch of silence, as Husyn Naqqash—a blind Muslim miniaturist, who was once the jewel at the Nawab’s court—implores him for a reaction to his painting. The silence is both deafening and piercing. The silence is also a shroud, which can conceal and heal at the same time—hide the scars and bruises, while giving warmth.

Painting partition

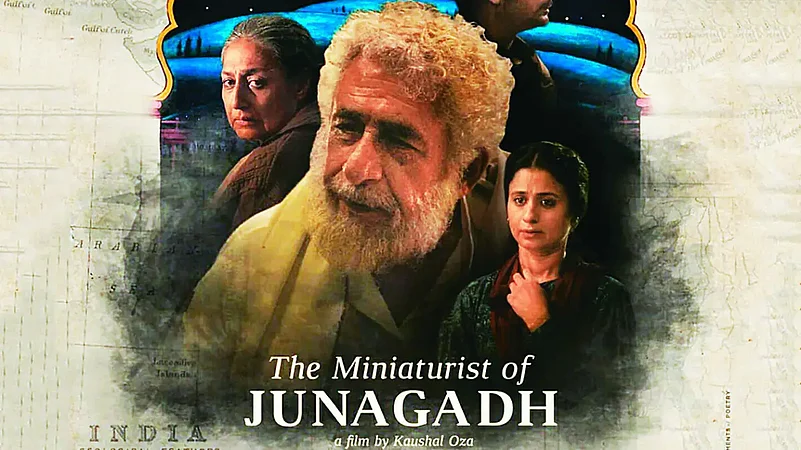

After being screened at various international film festivals, most notably the New York Indian Film Festival last year, The Miniaturist of Junagadh was released online in May 2022. More than conveying a sense of loss and longing, the 30-minute short captures the sheer helplessness of a person’s inability to preserve memory and moments.

It is the winter of 1947 in the princely state of Junagadh, Western India. Religious intolerance, riots, and massacres are playing out on stage in the theatre of Partition. On the one hand, the canvas of India is bloodied, and on the other, Husyn’s canvas screams blank glances of which the miniaturist with fading vision is blissfully oblivious. His daughter Noor and wife Sakina have been keeping a secret from him and Husyn’s blindness has camouflaged it for the longest time until Kishorilal shows up one day. Kishorilal is the inheritor of Husyn’s ancestral home. An arrangement made out of compulsion rather than choice.

Magic of miniature

In the aftermath of the hasty retreat of the Prince, the state of Junagadh is annexed to India, and this is why Husyn is compelled to sell off his ancestral home and eventually move to Karachi, Pakistan. Kishorilal is ready with the agreement papers that once signed by Husyn, will make him the legal owner of the house and everything else, including all the antique belongings of the family—be it the vintage gramophone, rosewood furniture, and traditional settees, among others. And, there is one more possession—priceless of all. The wooden box of Husyn’s miniature paintings.

Kishorilal is intrigued and promises to visit the same evening to have a look at the paintings. The thought of making big money on account of selling such rare paintings fills him with feverish excitement. It is evening. There is a power outage. Husyn and family will board the steamer from Porbandar that very night. The age-old secret is about to be unwrapped with the unboxing of the miniaturist’s treasure trove of exquisite paintings. The truth is there are neither any paintings nor miniatures, reveals Noor. She tells Kishorilal there is absolutely nothing of value in that box which would fetch him money.

Keeping a not-so miniature secret

What follows is a haunting saga narrated by Noor. In order to keep the violent mobs at bay, minimise threats from those who looted neighbouring Muslim households during riots, Noor and her mother Sakina started selling Husyn’s paintings. Little did they know, the collection of paintings would betray soon and they would gradually run out. All this kept unfolding on the side, while the blind miniaturist had no inkling of the clandestine trade. He would often sit with the box, running his fingers through the paintbrushes, dried colours, and of course, the priceless canvases, which, unbeknownst to him, were blank. Each time the mother-daughter duo sold a painting, they would replace it with a blank canvas. The more they filled the box with emptiness, the void inside their hearts grew wider. How would they have known that their charade would be exposed some day?

Kishorilal is visibly stumped when Husyn begins to narrate with childlike glee and enthusiasm the scene from the Battle of Panipat he had masterfully brought to life. Handing over the canvas to Kishorilal and cautioning him to not touch the colours, Husyn asks him what he makes of the miracle of the alchemy of light and colour on a lifeless canvas. There is a change of heart, a sudden transformation. Kishorilal remarks, “Chuppi hi zubaan hai,” thereby playing along as the third secret-keeper of a bitter truth. A smile escapes Husyn’s lips. The delicate mirror of nostalgia stays as is, undisturbed, untouched.

Can memory be demolished?

When the demolition of director Kaushal Oza’s ancestral home in Mumbai’s Borivali was an inevitable reality he could not prevent, he decided to make a film in the same home before losing it forever. In an interview with Shoma A. Chatterji for The Citizen, Oza recounts, “There was this historical house in Mumbai (belonging to my grandparents) which was about to be pulled down, and I wanted to shoot it to record the house for posterity.” And the story that immediately struck a chord with Oza was Stefan Zweig’s 1925 short story Die Unsichtbare Sammlung (The Invisible Collection). The Miniaturist of Junagadh was thus born.

Stellar performances

All the actors have gone beyond their brief to make this film a memorable one. Long after the credits roll, the mind wanders off to the aesthetic frames, rusty windows, and the old gramophone playing forgotten melodies. Naseeruddin Shah’s blank gaze sees more than the heart can absorb. His stance, gait and panache faithfully express the desperation of finding scraps and broken pieces of art in a world which is up in flames and where people are mercilessly killing their own. For Husyn, his blindness is not a loss but a reward of his profession. He takes pride in his blindness for he believes he has earned it as a result of being the finest miniaturist in the royal court. Rasika Dugal as Noor is the doting daughter who cannot see her father in agony. Padmavati Rao as Sakina delivers an impactful performance, while Raj Arjun as Kishorilal does more with his intense, sharp expressions than dialogues. An ensemble that is any director’s dream come true!

The intoxicating, mesmerising background score by Chhavi Sodhani adds to the palpability of the cinematic experience. The lilting music gently stitches the long, uneasy pauses; stealthy and helpless glances exchanged between the characters; and the ellipsis floating in the air heavy with sighs, together to create a mosaic of echoing silences. Chuppi hi zubaan hai. Silence. That is the response this film deserves. The Miniaturist of Junagadh is worth your time and space.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Mosaic of Silence")

Ipshita Mitra is a freelance writer who just launched her debut collection of 21 verses titled smudged ink and Other poems