- Renovation of the historic Lahori Gate, removal of ugly additions made by the army

- Restoration of elegant vaulted roof and arched bays of the covered, 17th century Chatta Bazaar

- Revival of immense forecourts connecting major buildings

- Restoration of Naubat Khana, Diwan-e-Aam, Rang Mahal, revival of Hayat Baksh and Mehtab Bagh Mughal gardens

- More areas to be opened up to the public, eyesores like metalled roads, roundabouts, squalid teashops and toilets, concrete water tanks to go

- Revamping of visitor amenities-signage, museums, information centres, restaurants, parking, access for the handicapped

- Original floor levels in the fort to be restored-some have risen more than a metre, spoiling architecture and causing heavy water seepage

- Work to begin next April, some changes within a year, but total transformation will take 10 years

True, it was the British who contributed the most to the sense of anti-climax you feel when you visit the fort, by destroying 80 per cent of its rich interior after wresting control of it in 1857, and leaving a handful of isolated, beautiful Mughal buildings to communicate the glories of what was once described as "the most magnificent palace in the East". But Indian neglect and hamhandedness have done their share. Lack of imagination, too. Sparse signage and dull museums fail to tell the riveting story of what the fort has witnessed over nearly four centuries: the grandeur and decline of the Mughal empire, looting by marauders like Nadir Shah, the last stand of the 1857 mutineers, royal halls plundered and turned into messes for British officers, the dramatic Indian National Army trials, the euphoric declaration of freedom from the fort's ramparts.

But now good news seems to be coming out of bad. In 2003, conservationists and the media raised hell over hasty alterations to the Red Fort—like crude inlay work, a prettified canal, 'farmhouse' style stone lights—that obliterated the original geometry and aesthetics. They were done under the watchful eye of Jagmohan, tourism and culture minister in the nda government, whose writ ran over the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), official conservator of the country's most important monuments. Having got the army, which has historically controlled large chunks of the fort, to agree to leave, the indefatigable Jagmohan had decided to do up the place.

As a result of the uproar, the ASI found itself on the wrong side of a 2004 Supreme Court judgement. The court froze conservation work on the site, pending the preparation of a conservation management plan to be okayed by a committee that included independent experts. Lawyer Akhil Sibbal, who represented cultural activist Rajeev Sethi and others in the pil that led to the judgement, points out, "For the first time, the Supreme Court has provided guidelines for the conservation management of a major historical site".

The unprecedented judgement appears to have opened the door for a massive effort to change the fort's fortunes. If all goes well, the dismal way this national icon presents itself will begin to be transformed, from mid-2007. It will be done, not ad hoc, or on anybody's whims, but according to a comprehensive blueprint currently being prepared for the long-term conservation of the fort. And, for the first time, the ASI is harnessing the talents of a multi-disciplinary team of independent conservation professionals to prepare that blueprint. Apart from the imperative to carry out the court's orders, an additional reason is the government's aim to bid forUNESCO World Heritage status for the fort next year.

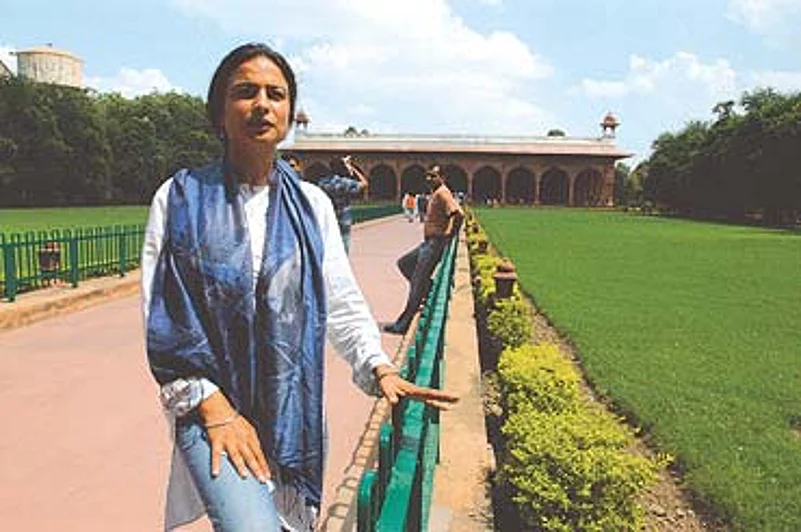

Conservationist Gurmeet Rai is leading a team of architects, historians, engineers, garden landscapists et al

Since April this year, conservation architect Gurmeet Rai, whom the ASI has contracted to put together the plan, has opened up the 120-acre site and its 400-odd structures—Mughal, colonial, post-colonial—to an array of professional consultants. Among them are architects and urban planners, art conservators, historic garden landscape architects, historians, material scientists, electrical and structural engineers.

They are documenting the condition of buildings and decorative work, correlating Mughal-era maps of the fort complex with the existing layout, establishing priorities for repairs, identifying opportunities, and what lost spaces should be recovered—for example, the lost Mughal gardens, like the fragrant night garden, Mehtab Bagh. Says garden conservator Priyaleen Singh, "We don't know much about the original gardens, but we do know what Mughal gardens would have looked like. I would like to put in place a long-term plan for phasing out many of the existing plants, and bring back the old system of planting to capture the spirit of the place as it was then."

Says Rai, "The goal is to understand the past, and project it into the future for conservation and management. The challenge is to make the monument readable to the common man."

The brief also encompasses visitor movements, services and amenities, and urban planning issues relating to the fort's buffer zone. NID-trained graphic designers are looking at signage, market research agency ORG-Marg has been hired to profile and poll visitors, a development economist is interviewing a complex range of stakeholders, including two security agencies, tourism officials, the ASI and the owners of 40-odd establishments, some five generations old, in the bazaar.

While the Jagmohan-led dispensation tried to get the shopkeepers evicted, leading to a legal battle, the new team sees them as part of the solution, rather than the problem. Interestingly, the shopkeepers' statements now chime with the new mantra of conservation. The market association has even hired its own architect to come up with proposals for restoring the ancient market.

An important part of the team's mandate is to recommend an action plan that would enable physical work to begin next year on the complex's central axis, in fact, the main visitor route, encompassing five important Mughal structures and the spaces around them: Lahori Gate, Chatta Bazaar, Naubat Khana, Diwan-e-Aam and Rang Mahal.

What good could it do the visitor? Well, sights lost to view like the vaulted ceiling and graceful arches of the Chatta Bazaar, said to be India's first covered bazaar, may once again be seen. Ugly additions to the Lahori Gate, by the British and Indian armies—inappropriate brickwork, rooms with asbestos roofs, cement floors—may be done away with. So also eyesores like iron-fenced roundabouts, with clumps of cannas, inappropriately located toilets, a hideous water tank and other modern blunders. The immense forecourts that once lay between the Chatta Bazaar and the Naubat Khana, and between the Naubat Khana and the Diwan-e-Aam, may be freed up, which will transform the chaotic approach to the Mughal pavilions. But some of the controversial 2003 interventions may be irreversible, warns Rai.

The ASI is in discussions with various specialised agencies on using ground penetrating radar technology to map original contours, which could then lead to excavations that will establish the foundations of ancient arcades and other structures destroyed by the British. The conservators are not looking to re-erect them. They want to identify foundations to be able to project—through landscaping, continuity of flooring and paving, or street furniture—the scale of the original and the unique relationship between built and open space in Shahjahan's architecture.

In such creative exercises lies, perhaps, the real excitement of conserving multilayered historical sites like the Red Fort. Conservation, stresses architect Abhimanyu Dalal, one of the consultants involved in the planning exercise, is not replication but a 'modern reinterpretation' or 're-imagining' of the past. Sometimes, it raises thorny issues. Not everyone loves the fort's 19th century barracks, blunt statements of colonial aggression that loom over delicate Mughal pavilions and have swallowed up Mughal gardens. Their fate has been a source of debate, but the prevailing view seems to be, as far as structurally feasible, to preserve the colonial imprint: keep and reuse these structures as museums, information centres, libraries.... Says Dalal, "Even abuses, because they are abuses by history, are an opportunity."