Why Gossip Is Good

Ashis Nandy, Political psychologist

"Gossip is a form of self-expression...(otherwise) frowned upon in authoritarian regimes. That is why it flourished during the Emergency, in Pakistan under Zia’s rule and now in Singapore. In Nehru’s time there was a kind of self-imposed censorship—people gossiped, didn’t dare to publish it. It gives a human touch to news but, at that time, it was seen as too trivial."

Mukul Kesavan, Writer

"Great movements are buoyed and moved by gossip. Virtually all institutional conversation—in universities, in government and in corporate offices—is gossip if we count the airing of speculation and anxiety about prospects, superiors and peers as gossip. The first gossip column I read (and the last) was Neeta’s Natter in Stardust."

Mani Shankar Aiyar, Politician

"Gossip is not a politician’s monopoly. I have never been good at it because I am too egoistic to take an interest in other people’s lives. Maybe that’s the reason whyI have never been a ruler and now never will be! I consider kaccha kaan the worst quality in people. The recounting of unverified stories as a form of amusement is a dangerous form of communication."

Sudhir Kakar, Psychologist

"Unlike rumour, gossip is a feelgood activity. Besides being the common gamesmanship of cocktail parties, it’s a harmless, healthy trend, helping to discharge feelings ofhostility and envy, even as it subverts those in authority. There’s also an element of sexual voyeurism about it. That’s why it’s associated more with women because telling tales is regarded as ‘feminine’."

Mushirul Hasan, Historian

"There was a certain innocence in gossip of the past. It was not designed to offend but to mock, to lambast and have fun. In the past, gossip first described a person’s good qualities before bringing him down. Now, there’s a greater degree of viciousness: it’s meant to harass, intimidate and destroy a person’s reputation."

Sanjaya Baru, Former media advisor to the PM

"It panders to a basic human instinct—everybody wants to know—and gossip satisfies that. That’s why gossip columns are so popular—the reader feels he’s privy to information he wouldn’t otherwise know. Media advisors of Sharada Prasad’s generation would probably not have approved, but parlaying information, even in the form of gossip, is now very much a part of the job description."

***

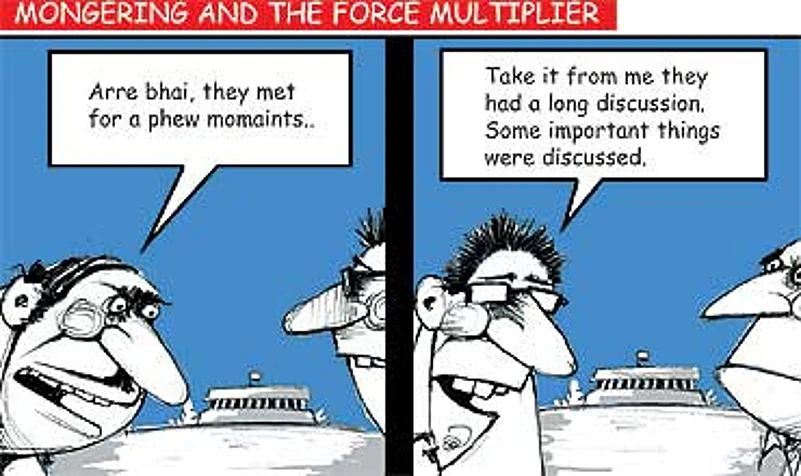

Click here for large image

Incidentally, despite the popular perception that women make better gossips, when it comes to the political sphere, it is the men who have perfected the art of gossip, walking that thin line between entertaining their leader with salacious stories about potential rivals without offending their patron by seeming too familiar. Remember how ex-raja Dinesh Singh fell from favour just because he had complimented Indira Gandhi on the sari she was wearing? It was not the fulsomeness of his flattery that caused his downfall, insiders vouch, but because he chose to do it within the hearing of his party colleagues. Others were more adept at it. For instance, when Karan Singh was once asked the secret of how he got on so famously with Mrs G, he responded without hesitation: "Gossip. She just adored gossip."

But it was not just her love of it that churned the gossip mill during Indira's rule. Driven by insecurity, she encouraged her ministers to carry tales about each other to her. She kept tabs on everyone, including her cousin B.K. Nehru, knowing exactly what he was up to at Raj Bhavan in distant Srinagar. No one could plead "personal work" as an excuse to wriggle out of a job he didn't want to accept. Mrs G's staff kept her briefed on every detail of her officials' life, as P.N. Haksar once gently warned an unwilling official. Her biographer and journalist Inder Malhotra gives an example of how efficient her gossip circuit was: The day after Emergency was declared, one of her cabinet ministers, Swaran Singh, confided in a friend: "Yeh thanedari nahin chalegi (this policing won't work)." "It took less than two hours for the remark to get back to her, and less than two months for him to be thrown out," Malhotra recounts.

But so compelling indeed is the need for politicians to gossip—whether it is to meet and run down rivals and colleagues, or to bare their souls to those they think they can trust—that few could resist it, even if it was at their own peril. Even a politician as famed for his reticence as Pranab Mukherjee succumbed to the temptation, as I.G. Patel, who was finance secretary during Indira's time, recounts in his autobiography. Having just received a phone call from Indira, asking him to chair the cabinet meetings on one of her foreign trips, Mukherjee couldn't keep the good news to himself. "I am now No. 2 in the government!" he burst out to Patil. The bureaucrat shuddered at the risk his minister was running: if it got back to Mrs G, it would be the "kiss of death" for Mukherjee, he writes.

It was during Indira's regime that gossip in the corridors of power took an unsavoury turn, according to veteran journalist Subhash Chakravarty. Her inner coterie, composed mainly of former Leftists, made it their business to plant stories about the personal lives of her rivals within the party. One such tasteless rumour was that Jagjivan Ram was suffering from a secret sex disease. "They (her coterie) were socially more savvy, and very good at running down people in a polished way, hitting below the belt," he recollects. Her rivals, whether it was Morarji Desai or Jagjivan Ram, simply didn't know how to respond.

Others agree that while gossiping was a favourite pastime of politicians even in Nehru's time, they did it with the confidence that nothing they said off-the-record would ever be reported. Two of the most memorable gossips of Nehru's time were Ram Manohar Lohia and Feroze Gandhi. The latter, in fact, had a regular adda going at his house, where a daily session of gossip, fuelled by cups of excellent tea and coffee, took place even before he fell out with his famous wife. Often she was the target, some say. Compared to Feroze, Lohia got carried away by his tongue, making derogatory remarks about both Nehru and his daughter. But it's an indication of those self-censoring times that the only comment directly attributed to Lohia was his description of Indira as "goongi gudiya". It got wide publicity only because he wanted it to; the rest stayed out of print, and will probably die with the few veterans who were the recipients of Lohia's gossip.

All governments rely on gossip, according to Sanjaya Baru, former media advisor to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. "It's part of the information-gathering process, after which you take a judgement call to decide on its accuracy. It has to be tested for the reliability of the source, any ulterior motives, and how factual it is." For instance, when a reporter he trusts told him about the crates of champagne found outside a certain minister's door while on one of his many foreign trips, Baru admits it was his job to carry that information to the PM. "It's part of the job description, much like the court jester of ancient times, who had to both amuse the king as well as keep him informed."

No wonder then that journalists have been actively courted since Nehru's time by anyone who wants to be in the know—businessmen, foreign diplomats, wheeler-dealers and, of course, politicians—wooed into attending cocktail parties, breakfast sessions, lunch (served personally Gujarati-style by Morarji Desai, for instance) and one-to-ones in Gymkhana Club, where they hoped to escape notice in the crowd. The practice continues now with parties for every occasion, including "mango parties" or biriyani-and-kabab evenings. Nothing fuels conversation—and what is conversation, after all, but gossip—better than good food and liquor.

Politicians are as compelled to gossip as ordinary folks, says political psychologist Ashis Nandy. In fact, the more famous you become, the more you need to share with someone you can trust. "Give any politician two hours and four whiskies and he'll turn into a gossip. It's a human tendency. He needs to share, and looks for someone he can trust before he confides his secret hopes and anxieties," he says.

Nandy confesses that he himself has often been the recipient of gossip from celebs across a range of professions—sportsmen, scientists, film directors, thinkers and writers. And this despite being inept at it. "You have to take it with a pinch of salt to really enjoy it. And provide the right cues—be slightly shocked, for instance. But I'm in awe of it—it reveals an important part of the person who is gossiping—I take it seriously."

According to historian Mushirul Hasan, royals needed a good gossip so much that by medieval times, they even institutionalised it, appointing someone called a Hajv, whose only role was to collect and purvey gossip in an acceptable form—in flowery language, interspersed with verse. Apart from giving the king information about potential adversaries, the Hajv's main job was to pull down the king's rivals without getting too offensive.

Gossiping became a highly developed skill in feudal life, according to Hasan, "linked deeply to the art of storytelling". Unlike women's gossip, which was "very domesticated", men's gossip was mostly directed against authority figures, whether it was their rulers or the nobility. It became a favourite public activity, both for its entertainment value as well as being a harmless way of subverting authority and humanising it.

The other quality of a good gossip, as Nandy points out, is that "you're expected to contribute". Journalists in the business of gathering news agree that gossip works only when it's a fair exchange. For instance, when journalist and biographer Rasheed Kidwai first met the late Congress president Sitaram Kesri, the latter asked him, "Have you come to take or give?" The question acutely embarrassed Kidwai, who was well aware of Kesri's reputation with young men, but he soon learnt that all politicians are looking for information about their associates as much as journalists are.

Kidwai feels picking up gossip is an essential part of a news reporter's job—even if it never gets into print—and very little does, even in these gossipy times. It explains what's going on behind the scenes. Agrees Coomi Kapoor, one of the first journalists to go public with her identity on a political gossip column. (Anonymous political gossips, on the other hand, have been around since at least the middle of the 19th century.) "Such gossip columns are no different from news; they're as factual, but often help us understand how the government works," she says. For instance, if you want to know why Kamal Nath was "demoted" from the commerce ministry, or why S.M. Krishna was a last-minute choice, or whether the running down of the PM in cabinet meetings has now stopped after his two main rivals are out, it's the gossip columns that give you a hint, not the news pages.

The only difference between gossip in Nehru's time and now, as veteran journalists point out, is in perception: what was once considered trivia is now a crucial ingredient of news. To paraphrase what Nigel Dempster, Britain's most famous gossip writer, once said: "If gossip is trivial, then all of life is trivial."