Why is India the sixth power?

It’s now in a distinct category. It keeps its nuclear weapons and can also now buy nuclear technology in the world market. Only the US, UK, France, Russia and China have this privilege. Nuclear blockade ends.

But what about the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty?

India’s exceptional nuclear status recognised even though India has not signed the NPT.

Why was this exception made?

As recognition of India as an emerging power, its responsible record on non-proliferation, its vibrant democracy, strategic importance, growing economy, large market and knowledge industry.

Challenges abroad?

India will have to balance its new proximity to the US with good relations with other major powers such as Russia. It will also have to prove its leadership in an unstable neighbourhood. Toughest country to handle? Obviously China, given Beijing’s attempts to hem India in. Latest example: Chinese duplicity during the NSG battle despite India’s extreme overtures, including restrictions on the Tibetans, the Dalai Lama, and playing down border violations.

Challenges at home?

You know them well: poverty, infrastructure, education, communalism and separatism.

***

We have the power: India celebrates the NSG waiver

After endless hours and many heart-stopping moments of negotiations, the Nuclear Suppliers Group, a cartel created in the 1970s specifically to deny India nuclear technology, agreed on September 6 to give India a waiver from its strict guidelines. The decision formally ended over three decades of denials, and more of bitterness. Those who gaze only at their own political navel do not appreciate how tectonic a shift it is in the calcified thinking of the status quo world where the already powerful rarely accept the newly emerging and advantaged rivals work hard to pretend, postulate and pontificate against the one outside the door. "For the first time," says a senior official, "we have brought the international system to a point where it suits us. India has entered the nuclear mainstream."

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, mysteriously patient and quietly firm, prevailed in the end, winning the confidence vote. He has earned his place in history as the leader who wears two crowns—unshackling India at home through economic reforms and liberating it abroad from nuclear apartheid. "If he had stood up too early and quit a year ago, people would have admired his principled stand," says a political analyst. "But by being patient and determined, he got something historic for India."

The success of the Indo-US civil nuclear agreement brings India closer to the United States and marks a new stage in Indian foreign policy. President George Bush, who got Iraq wrong, got India absolutely right. He was able to cut through the cobwebs of old think in Washington, push for a huge policy shift and shake up a bureaucracy steeped in suspicion. Many Indian officials, generally shy of embracing a US president even in words, were effusive about Bush last week. He weighed in at every difficult moment and called world leaders to stand down in the NSG. As an insider put it, "Without the US leaning on them, why would 45 countries break their heads over this?"

The nuclear deal is a net gain. Foreign secretary Shiv Shankar Menon told Outlook, "The long-term implications of this will increasingly become apparent because it’s the first step in dismantling the technology denial regime. India wants to build a knowledge-based economy because that is the future." The ending of the ban will mean technological upgradation in various sectors and a multiplier effect.

India is no longer a nuclear pariah for the world. Those who invoked India and Pakistan in "the same nuclear breath" as two bad boys will have to rethink. The hyphenation with Pakistan is decisively and formally over. Beijing may not like it but the world now strategically equates India with China. The games Beijing played in Vienna on the India waiver were duly noted by Delhi and will be built into future calculations. "They know that we know: the rest is detail," says an official. In the end, all 45 NSG countries were persuaded, mainly because they saw India as a responsible nuclear power with a potential to play an important role in world affairs.

Men who mattered: Special envoy Shyam Saran, foreign secy Shiv Shankar Menon, Nicholas Burns, US ambassador David Mulford

"The world recognises that India has made positive contributions. Our responses to provocations from our neighbours are measured. We have managed better than almost any other developing country on every front—free speech, human rights, knowledge-based industry, science. No developing country has the spectrum of soft power India has shown in the arts, culture, films and literature," says Naresh Chandra, former cabinet secretary and ambassador to the US. "India has been affecting the consciousness of nations for a while. We are seen as a people who will contribute to the welfare of the world." No one worries about the peaceful rise of India.

But the new world environment, which India faces as the sixth power, is pregnant with challenges and responsibilities. There are expectations of a myriad kind, pulls from the neighbourhood, and requirements on non-proliferation, including difficulties around Iran’s nuclear quest. At home, it faces debilitating institutional and political strains which hamper its rise. Can India meet its own aspirations and those of others?

India and the US, now confident friends, will work together where their interests converge as they have on the nuclear agreement, tsunami relief, fighting terrorism and global health issues. Where they don’t, the two will be at loggerheads as in the World Trade Organisation and climate change. Those who fear India will pawn its independent foreign policy as a "thank you" to Washington actually lack self-confidence, officials say. "Why do they always overestimate America’s abilities and underestimate India’s?" asks a former diplomat. But proximity to the US will mean an excruciating balancing act as India juggles its relations with Russia and China, the two other biggies on the block. Perceptions of India’s closeness to the US will dictate calculations in Moscow, which is engaged in a showdown with Washington in its "near abroad". Russia resents NATO at its door and the US role in the Georgia crisis.

Russia occupies a special place in the Indian mind because it has been a rock in times of trouble. But how India insulates that special feeling from the new love of America will be the diplomatic tango to watch. Moscow feels pushed to the wall by Washington, and the future may force India to take sides. "The evolving global landscape is very complex," says a former foreign secretary. "But we have to deal with the world as the world is. The task is to create more and more options for India with diverse relationships with all major powers."

The US, still the pre-eminent military and economic power, remains the most important source of technological and scientific innovation. "If India wishes to modernise its economy, partnership with the US is logical," says a senior advisor. The US too is looking for new partners in Asia, the continent that has claimed this century. India’s sheer size, prime location and military strength make it an attractive choice.

The US will have expectations, whether on the commercial front or strategic, although a close relationship with India in itself is seen "as a plus" in Washington. The Pentagon is always keen to enlist more help from India, especially after the cooperation during the 2004 tsunami. Okay, these guys can do it, was the US reaction. The Americans understand that India is not about to prosecute a war with them, nor will it take absolutist positions against its neighbours, says a diplomat. But New Delhi understands that only after the US-India partnership became a reality did China begin to take India seriously and shed some of its patronising attitude.

Ayes and nays: Ahmadinejad with Hu Jintao; (Below)Sarkozy with Putin. France and Russia backed India unequivocally, but China gave a reluctant nod. Iran, of course, could be a future sticky point.

The US, India and Southeast Asian countries want a more balanced security architecture in Asia to adjust to China’s rising economic and military power. "It’s not containment because everyone is engaged with China," says the former foreign secretary. "But it is an attempt to draw up a system, which raises comfort levels. Everyone wants to hedge their bets. You have to assess China realistically and you need a whole range of policies. How you play this game is important. You are part of the transformation now."

It is also true that the world’s acceptance of India as China’s strategic equal is not happy news in Beijing. China does not embrace the idea of India as a permanent member of the UN Security Council nor as a member of the "inner ring" of Southeast Asian nations. China fed Pakistan’s nuclear and missile programmes against India, hemming it into a South Asian fight. "The nuclear arming of Pakistan was brazenly irresponsible," comments a former ambassador. "Pakistan was persuaded to follow an impossible policy of parity with India. How could those deep Chinese thinkers miss the fact that the gap between India and Pakistan would keep widening?"

But the India-China relationship is multi-layered and complex. Bilateral trade has made a great leap forward—it was $38 billion last year, defying all projections. Indian companies are marking a presence in China and the two countries have similar positions on climate change and the wto. But there are adversarial elements too, the most important being the border dispute and China’s large and strategic footprint in India’s neighbourhood.

To counter India’s new status, China may try to grab even more ground in India’s neighbourhood, build more alliances and offer more lucrative deals to gasping governments. China looms large in Nepal, even though India has been Nepal’s oldest and most dependable friend. Nepal’s new prime minister, Prachanda, has said he wants a policy of equidistance between India and China and renegotiate the Indo-Nepal Friendship Treaty, as a mark of independence. In Sri Lanka, China is developing the Hambantota port in the south at the cost of $1 billion. China has replaced India as Bangladesh’s largest trading partner. It has made inroads into its defence forces, supplying weapons and F-7 fighters. It plans to connect Chittagong to Kunming in Yunnan via Myanmar, but the Myanmarese are not playing ball. "China’s capacity to deliver is enormous. They are all over Myanmar," says a diplomat. "India will face consequences if China has a free run in the neighbourhood." The solution is not fear but good policies for good neighbours, even at terms too generous.

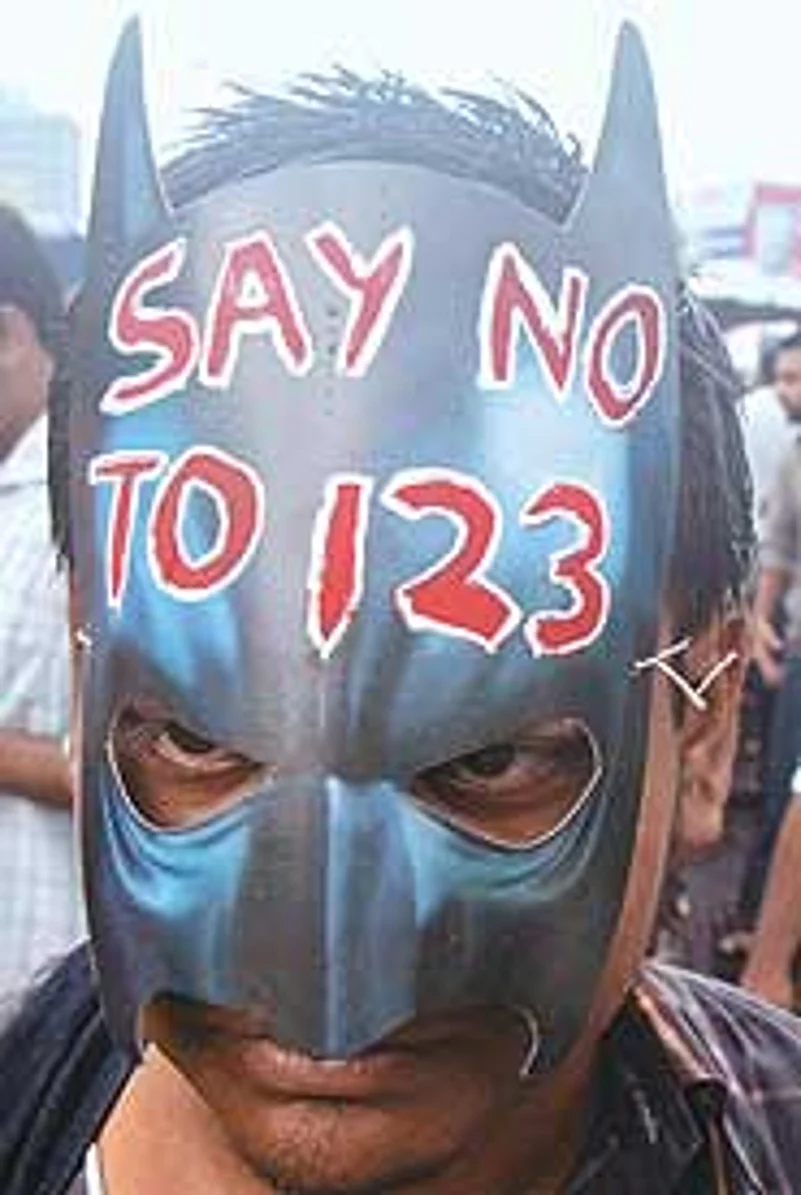

| Anti-nuclear deal protest in India |

India's most difficult relationship is China’s best—Pakistan. China and Pakistan share an "all-weather friendship", often deemed to be "higher than the Himalayas". It even tried to expand the NSG waiver to include Islamabad to recreate parity between India and Pakistan but there was zero support. Although Pakistan wants a similar nuclear deal from China, the NSG is highly unlikely to move given Islamabad’s dark proliferation record. Apart from nuclear technology, China and Pakistan have many big ideas. Both countries plan to link the Karakoram Highway, which goes through disputed Indian territory, to the southern port of Gwadar through the Chinese-aided Gwadar-Dalbandin railway. The rail links extend up to Rawalpindi.

On the surface, India and China will maintain "peace and tranquility" and build on rapidly growing trade relations, but the brains will continue ticking on future scenarios. If the first concentric circle of Chinese influence around India is the immediate neighbourhood, the next consists of Central Asia and Southeast Asia where the two are trying to gain ground. China has a head start because its engagement began in earnest more than a decade ago.

Of the six transport corridors envisaged between Central Asia and Europe by the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation or CAREC—a programme of the Asian Development Bank—five originate in China. China has invested $600 million on roads in Tajikistan. It has bought rights to uranium mines in Kazakhstan and built an oil pipeline. Observers say that Pakistan has been telling Central Asian leaders that the Karakoram Highway would be their access to warm ports, taking delegations by road to prove the point. Central Asia forms the clasp on China’s "string of pearls" policy. The policy aims to increase Chinese access to ports and airfields from the South China Sea through the Straits of Malacca, across the Indian Ocean and on to the Persian Gulf. Some strategic analysts see this as a possible bid for regional primacy down the line.

Meanwhile, India has been slow to deliver on promises made to Central Asian leaders with files moving back and forth in perpetual motion and project implementation delayed beyond belief. This raises the question whether India has the institutional and political capacity to play a larger role in the world. On the one hand are the enormous domestic challenges of poverty, appalling infrastructure, over-stretched institutions and corruption, and on the other is the inability of the politicians to rise above partisanship for the greater good. In the end, unless the political establishment renews its pledge to the country, India will trundle along with bright spots and dark ones.