Spring is the time of the year people in Rawalpindi stay outdoors late into the night, relishing the balmy breeze that spreads exuberance all around. On March 30, though, as Pakistani batsmen stumbled against Indian bowling, and a waning moon shone in the sky, an eerie silence enveloped Rawalpindi. It seemed as if a curfew had been clamped on the city, reminiscent of the troubled times of the 1965 and 1971 wars, during which wailing sirens would punctuate the interminable silence. This gloomy picture was in sharp contrast to the mood earlier, when Pakistani bowlers were spinning a web around the famed Indian batsmen—each dismissal followed by a volley of shots, optimism soaring even as stray bullets injured five people in Hyderabad.

Suddenly, loud bursts of firecrackers tore asunder the midnight silence in Rawalpindi Cantonment, a security ‘Red Zone’ where surely Indians couldn’t have descended to celebrate their triumph. Could the Pakistanis, under the sway of cricket diplomacy, be sending up rockets to share in the joy of the people across the border? As I ventured out to investigate, I saw boys distributing boxes of mithai. My confusion was dispelled as 13-year-old Rahim Ejaz, freely mouthing expletives, said sarcastically, “We had saved up these fireworks and mithai for Pakistan’s victory but we are now bursting firecrackers in protest against Misbah-ul-Haq’s batting, the terrible fielding and Umar Gul’s bowling. (Interior minister) Rehman Malik had warned against players throwing the match. We are suspicious.” A few expressed their anger by hurling down TV sets from their balconies, and some women wept.

Cricket and religion are two prime obsessions of the subcontinent. Following the debacle in Mohali, the fundamentalist crowd in Pakistan threw itself to resolving, in all earnest, that impossible conundrum: Why did Allah betray the Pakistani team, comprising Muslims? Journalist Ansar Abbasi, who had earlier praised Afridi and his team for showing the guts to pray publicly in Mohali, wrote in The News: “The Holy Koran is desecrated and we remain unmoved and a small number of people come out in the streets to lodge their protest. American killer Raymond Davis is released in a shameful manner, insulting the whole nation. Our people are killed every now and then by US drones. We have no money for the poor but billions for the ruling elite. Our failings are too many. Then why do we pray to Allah to listen to us? Let Afridi play cricket.”

Younus Khan drops a Tendulkar catch. (Photograph by AFP, From Outlook, April 11, 2011)

An SMS doing the rounds on Thursday morning underscored the sheer irrelevance of such questions, of framing Indo-Pak matches in religious terms: “Since the Mohali match was declared a war between the believers and non-believers, I humbly submit that the mothers of Zaheer Khan and Munaf Patel are more pious Muslims than those praying in Pakistan.”

These remarks provide a glimpse of Pakistan’s collective dismay, which was aptly articulated in the Express Tribune Page 1 headline, “The dream is over.” Below it was the photograph of Pakistani captain Shahid Afridi, eyes closed, hands clasping his head, with the caption, “I want to say sorry to my nation.” The knives were out for the man who had bowled brilliantly through the tournament. Former captain Aamir Sohail wrote: “Pakistan lost because of poor captaincy. I have been saying that Afridi’s defensive attitude is going to cost Pakistan.” Sports writer Mohsin Ali argued, “Pakistan did not bother to take Powerplay until it started automatically. The Pakistani team was completely outclassed.”

Success, it’s said, has many fathers and defeat none. Defying this dictum was sports journalist Rizwan Ali, who told Outlook, “I am surprised that this team reached the semi-final. I was not expecting them to take the Cup. It would have been a miracle if we had. Remember, Pakistani media has been ruthless these past 10 months against this team, specially Afridi. At least now they can have their catharsis.” Rizwan’s remarks, in a way, underline the absence of logic in Pakistan’s dream—you trenchantly criticise a team for its weaknesses, yet you expect it to win the World Cup, forgetting its achievements were anyway quite incredible.

The dream-run of Afridi’s men till the semi-final blinded cricket fanatics to the foibles of their own team. Former captain Imran Khan was pilloried for declaring, “The Indian team has the best opportunity of winning the World Cup this time, given its track record and consistent performance. They are certainly the favourites.” How dare Imran back the rival, thought many, for whom spinner Danish Kaneria’s lavish praise of the Pakistani team the morning after the defeat would seem a cruel joke. Kaneria wrote, “Pakistan must be praised for an extremely energetic and fighting spirit that they brought to Mohali. They performed outstandingly with the ball and the youngsters in the team will pave way for a bright future for this team.” For devastated Pakistanis, the future ended abruptly on the night of March 30.

Barred view Pak and Indian prisoners watch the match in Karachi

The Pakistani dream of lifting the World Cup was, in a way, also a measure of the nation’s hunger for good news. Wounded almost daily by suicide bombers, devastated by floods last year, bestowed with a political class narrow in its outlook and too weak to combat the fundamentalist forces, the nation looked at cricket for respite. Had the team lifted the World Cup, had they at least vanquished the Indians, the stupendous feat could have been seen as a riposte to those who have scratched out Pakistan from their cricket itinerary and penalised its three leading players for spot-fixing.

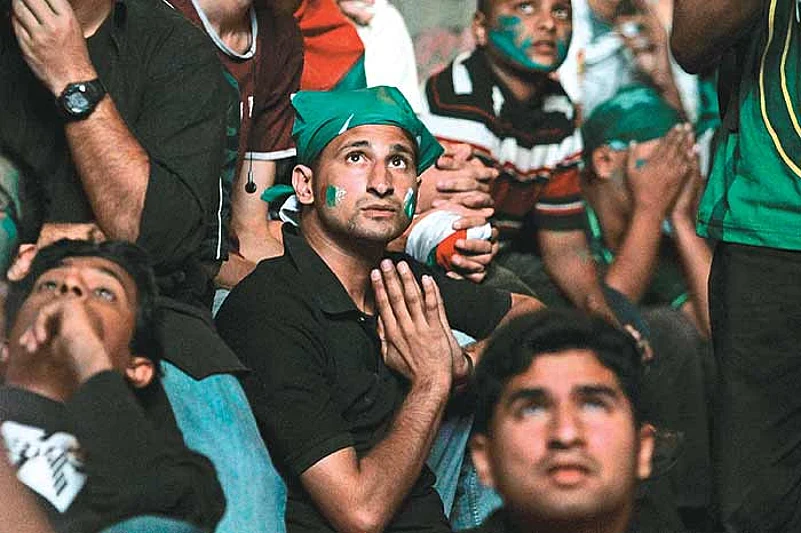

The astonishing performance of Afridi’s men in group matches only encouraged the nation to dare to dream. The time hadn’t come yet for those dropped Tendulkar catches. Pakistanis jammed most main roads with cars and motorcycles, with youngsters dangerously craning out of cars with the green-and-white flag held high, music blaring, shouting, “God is great! The world is green today.” The excitement proved unbearable for Liaquat Soldier, a comedian, who suffered a fatal heart attack on a live TV show on cricket.

The fervour in Pakistan was unprecedented—tribesmen in Pakistan’s restive N. Waziristan were seen cleaning their guns for celebratory firing; giant screens had been mounted at Lahore’s Gaddafi stadium, so also in the parks and food streets of Rawalpindi and other cities; and cinema halls were telecasting the match alive. “Lala Chumma,” the crowds roared each time Afridi, who’s affectionately called Lala, appeared on the giant screen. And mind you, all this in a country where people are apprehensive of crowded places, which have often become the target of suicide bombers.

What was unique in this collective fervour was the absence of strong anti-India sentiments. India was looked upon as just a cricketing rival, not an ideological enemy, not a foe against whom wars have been fought. No doubt, there was much banter, best reflected in one sms a day before the semi-final: “Hindustan walon, tumhari Sheila jawan hai, Munni badnaam hai. Khayal karo, hamara Afridi Pathan hai.” Perhaps Pakistanis realised that the thrill of a cricket match requires India in opposition, or that an Indo-Pak match is a symbol of two separated brothers at least coming together to match their cricketing skills.

Perhaps the temperature was lowered because of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s cricket diplomacy—his invitation to Pakistan Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani imparted to the semi-final a carnivalesque touch. In a jail in Karachi, Pakistani and Indian prisoners, wearing their country’s colours, assembled behind their own flags to watch the match on a giant screen. Pot-bellied policemen danced with abandon. No wonder, foreign office spokesperson Tehmina Janua says, “Mohali was a ‘win’ for the Pakistan-India dialogue process.” And Enver Baig, a ruling party senator, says, “Though Pakistan lost the battle at Mohali, as far as diplomacy is concerned, I feel it has been a tremendous opening after the great misunderstanding on Mumbai. Both governments should take this opportunity to make a new beginning and put in sincere efforts to bring the two people together.”

But Dr Shireen Mazari, CEO, Strategic Technology Resource, an NGO, begs to differ. “The match and cricket diplomacy ended as expected, both in a whimper,” she says. “Just as Pakistan was unable to counter the highly professional and well-trained Indian side, Gilani was unable to raise issues like India’s interference in Balochistan.”

Perhaps cricket diplomacy, as in the past, is unlikely to yield concrete gains in the long run, unless politicians from both countries show resolve. For the moment, though, Rehana Khan, who works for an ngo, is happy to chirp, “So what we lost, the Cup still stays in Asia.” For people like Rehana, the choice is clear—the thrill of a Pakistan-India match is any day preferable to the deathly silence of a frozen relationship.