The protracted, even duplicitous, negotiations between the UPA government and the Opposition over the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Bill, 2010, must have surely given the heebie-jeebies to those in Washington who are responsible for preparing US President Barack Obama’s visit to India in November. As the Liability Bill generated headlines and stoked passion all around, the overwhelming signal to the US was—there isn’t yet a consensus amongst India’s political class about its relationship with America. Worse, several new wrinkles seem to have surfaced in Indo-US relations precisely at that juncture when officials of the two countries should have been carving out the agenda for Obama’s November visit.

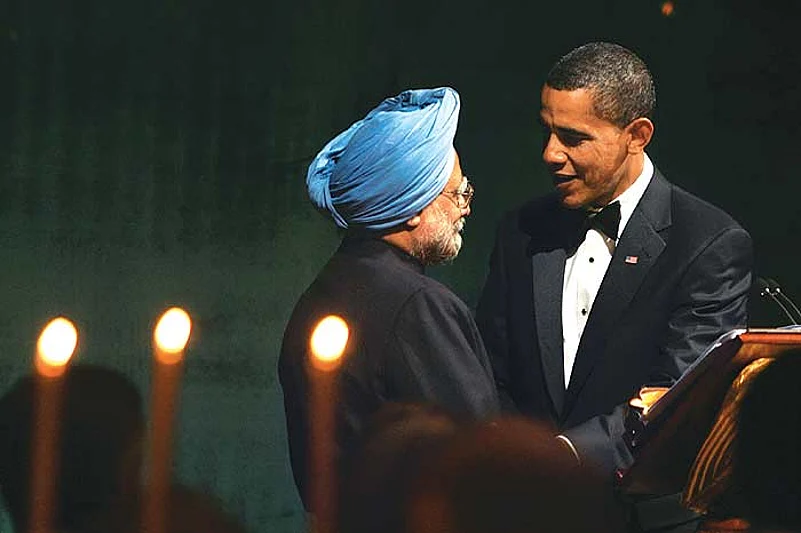

In some ways, this must depress the Obama team—though he’s the third American president to visit India in 10 years, he’s the first to make the journey in his first term. The eve of the visit should have been marked by excitement, expectations and grandiose plans. Instead, as the debate over the Liability Bill demonstrated, questions are being asked about whether the Indian government has been too accommodative of America’s interest even as Washington has ignored or downplayed India’s.

The rancorous ferocity of last week’s debate, as also several pending issues (see infographic), suggest Indo-US relations are not as robust as they were under George W. Bush. True, the Liability Bill was passed, but only after the government agreed to drop the controversial clause that sought to indemnify companies from culpability and liability in the event of a nuclear accident. This was the clause the Americans were keen on because their companies, unlike those of other countries, do not enjoy state support; the possibility of huge compensation payment renders it difficult to secure insurance cover, without which companies are wary of doing business. However, companies enjoying state support are not as badly strapped for insurance. Consequently, the Americans insisted on the indemnity clause, claiming their companies, in competition with those of others, won’t have a level-playing field in India.

The deletion of the indemnity clause, admit officials in the ministry of external affairs, is likely to agitate the US and its companies. It was, after all, the US that had used its formidable weight to secure India a waiver from the Nuclear Suppliers Group—for its firms to be placed at a disadvantage in the competition to grab the Indian nuclear pie would seem to be an odd recompense. These officials, however, say the US will ultimately realise the UPA government couldn’t circumvent Parliament.

No one in America can blame Manmohan for failing to deliver what he had promised though. His government tried its best to smuggle in the clause seeking to indemnify nuclear suppliers. The Americans, say sources, were kept in the loop at every stage of the debate, every time a clause was deleted, inserted or rewritten. Manmohan was even accused of promoting US interests, of being soft on them. As former secretary in the MEA, Rajiv Sikri, told Outlook, “The pertinent question to ask is why the government had not deleted the clause on its own. Perhaps it was trying to bat for someone who was definitely not Indian.”

The odds, however, were stacked against the Manmohan government. For one, intense recent scrutiny of the Bhopal gas tragedy loomed large. Weeks had been spent debating the plight of victims of the world’s worst industrial disaster and how Union Carbide, an American company, got off the hook. The media spotlight had been trained on New Delhi’s failure to extradite Carbide president Warren Anderson, an American national, even after 26 years. This backcloth made it well nigh impossible to protect nuclear suppliers from compensation and culpability for nuclear accidents. Bhopal is one reason why Indian diplomats feel the Americans will condone the UPA government’s failure to deliver on the liability issue.

Foreign secretary Nirupama Rao too says the liability issue won’t become a problem between India and the US as their relations have matured to an extent that they can understand each other’s problems and discuss these with candour. “Indo-US relations are now acquiring increasing maturity to become more multi-dimensional. They are no longer unifocal,” Rao told Outlook.

Yet there are many in the foreign policy establishment who wonder if India enjoys the same kind of status under Obama as it did under Bush. Several new stress-lines have surfaced—for one, there has been a hike of $2,000 for each H-1B visa, thus adversely impacting the Indian IT companies which send their workers to the US. Second, several key Indian organisations remain in the American Entities List, thereby restricting transfer of high technology from the US to India. More importantly, the Obama administration seems keen to outsource the management of Afghanistan to Pakistan, bypassing Indian interests for tactical reasons. Says former foreign secretary Lalit Mansingh, “You cannot have a meaningful strategic partnership when some of your top organisations are in the Entities List.... There is nothing called a perfect marriage. But to make it tick, both sides have to work hard.”

But not every Indian crib needs to be taken seriously; this ruse is often adopted more for “optics” than out of real fear. For instance, some diplomats say that though New Delhi has protested vehemently against the H-1B visa fee hike, this is unlikely to hamper the IT firms operating in the US. “But if we don’t scream and make a song and dance about it, they may put additional burdens,” says a senior official in the MEA.

Some feel India must also do its bit to make its relations with the US robust. For starters, it must shed its “developing country” mindset and not see the devil in every US intiative, opposing things merely because Washington is the progenitor. Diplomats say this factor is the reason why India hasn’t yet signed three crucial agreements—the Mutual Logistics Support Agreement, the Communication Interoperability and Security Memorandum of Understanding Agreement (CISMOA) and the Basic Change and Cooperation Agreements for Geo-Spatial Cooperation (BECA). These agreements sought to give India access to sophisticated information and data pertaining to the military hardware New Delhi buys from the US. Since these were mooted during the UPA-I rule, the Left forbade the Manmohan Singh government from entering into a tighter US strategic embrace. Sources say these could be signed during defence minister A.K. Anthony’s visit to the US next month.

Former Indian ambassador to the US Naresh Chandra says, “We are no longer the country we were in the early 1990s. The India of 2010 is a confident country, but it has to reflect this in its attitude.” It is an argument that cuts both ways—true, it shouldn’t suspect every US initiative; but it shouldn’t agree to every demand of the US either. Analysts feel India should harness its growing economic clout to bargain hard with the US and protect and nurture its interest. With the Indian nuclear pie expected to be around $150 billion by 2030 and New Delhi expected to make military purchases worth at least $110 billion in the next 12 years, it could grant concessions to the US here for a quid pro quo in another area.

As officials begin preparations for Obama’s visit in November, India would want him to clearly express his resolve to counter terrorism emanating from Pakistani soil and accept that New Delhi deserves to play a role in Afghanistan. It would also want Obama to show unambiguous support for India’s quest to secure a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. Should America ignore some of these issues, Obama’s November visit could fail to conjure the Bush or Clinton magic.