- 1911: Tibet becomes an independent republic

- 1935: A boy born to a peasant family in northeastern Tibet is declared the 14th Dalai Lama two years later

- 1949: Mao Zedong proclaims the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Threatens Tibet with ‘liberation.’

- 1950: China invades eastern Tibet

- 1951: China forces Tibetan leaders to sign a Seventeen Point Agreement. It professes to guarantee autonomy to Tibet, respect the Buddhist religion, and allows China to build civil and military headquarters at Lhasa.

- 1954: The Dalai Lama and Mao meet in Beijing

- 1959: Full-scale uprising in Lhasa. Thousands die. The Dalai Lama and most of his ministers flee to India, followed by another 80,000.

- 1965: Chinese government establishes the Tibetan Autonomous Region

- 1966: The Cultural Revolution reaches Tibet. Many monasteries destroyed or shut down.

- 1980s: China introduces "Open Door" reforms and boosts investments in Tibet

- 1987: The Dalai Lama calls for the establishment of Tibet as a zone of peace, seeks dialogue with Beijing

- March 1989: Martial law is imposed in Lhasa after days of rioting

- August 1991: Talks between the Dalai Lama and China break down

- 1994: The Dalai Lama suspends dialogue with China due to lack of progress

- December 1999: The Dalai Lama says Tibetans would be satisfied with self-rule but accuses the Chinese of cultural genocide

- 2002: Contacts between the Dalai Lama and Beijing resume

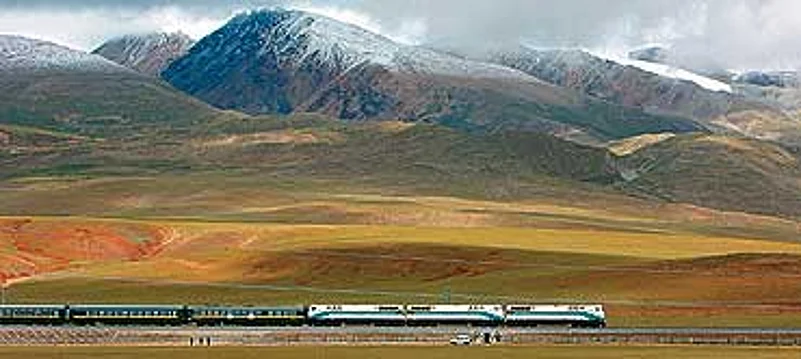

- 2006: China opens Qinghai-Tibet Railway, the world’s highest railroad, saying it will help develop Tibet. Critics say it is accelerating the influx of Han Chinese

- March 2008: Protests against Chinese rule escalate into the worst violence Tibet has seen in 20 years

***

Tibetan rulers and Mao signing the 17-point Agreement in 1951

Stoked by years of enmity between the native Tibetans and the immigrant Han Chinese, the suppressed fury of crowds erupted, targeting every mundane sign of China’s presence in Lhasa. Protesters attacked Chinese shops and offices, ransacked property, beat up Chinese policemen and set their vehicles on fire. For all the rage on the streets though, there were few signs of premeditated action. Only a few unfurled the banned Tibetan flag or mounted photographs of the Dalai Lama, their exiled leader. Several shouted "Free Tibet".

As the riots spread, violent clashes between the police and the protesters ensued. Gunshots rang over the ancient capital and paramilitary troops began to encircle the centre of the city, sealing it off from the outside world. The accounts of the aftermath vary greatly. The Tibetan government in exile, which is seated in Dharamshala, maintains that at least 80 people died in the riots. Beijing disagrees. Qiangba Puncog—chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region and the equivalent of a provincial governor—put the death toll in the violence between 13 and 16 "innocent civilians" and three who died jumping out of buildings to evade arrest. Pointing fingers at violent mobs "linked to the Dalai Lama clique" as perpetrators of the riots, Qiangba Puncog, an ethnic Tibetan, said, "The means the violent mobs used were so cruel that they make one bristle with anger. We will deal harshly with these criminals in accordance with the law."

But even as the deadline—March 17 midnight—set by the Chinese government for the protesters to stop or face a crackdown loomed, the riots spread to other Tibetan-populated provinces. At the holy site of Labrang in Gansu province, hundreds of monks and lay people marched in peaceful defiance. Some townships in Qinghai province reported lowering their Chinese flags and raising Buddhist flags before being swarmed by riot police forces.

Observers here say the challenge to Beijing’s control of the restive region is now at the greatest since a larger uprising was suppressed and martial law imposed in March 1989. "There have been incidents, and some violent ones, in previous years too but nothing of this scale," says Professor Wang Yao, expert on Tibetan affairs with the Central University of Nationalities in Beijing.

The disturbances overshadowed an annual display of social stability when Chinese leaders, including those from the Tibetan province, attend the March session of the National People’s Congress. They rubber-stamp the government work report and every five years, as it was the case this year, vote in the new cabinet, handpicked by the Chinese Communist Party, to lead the country.

But there was more to the Tibetan mayhem that embarrassed image-obsessed Beijing. The bloody riots unfolded under the intense glare of the international media, which has been zooming in on China’s rights record as Beijing readies to host the Olympic games. Arson fires blazed in Lhasa only two weeks before the Olympic Torch is to arrive there, kicking off official celebrations for the Olympics. Chinese leaders regard the games as a symbolic endorsement of their country’s growing global clout. Beijing has spared no effort to prepare a lavish "coming out to the world" party, hoping to win hearts and minds with a show of national unity and well-being.

The Qinghai-Tibet railway

With so many eyes focused on China, the Tibetan exile community and rights activists have seen an opportunity to press the Tibetan cause, which has largely foundered in recent years as China’s international profile has grown. "China must not be allowed to parade the Olympic torch through Tibet while hundreds, possibly thousands, of Tibetans are tortured and brutalised in Chinese detention cells," said Matt Whitticase of Free Tibet Campaign in a statement.

China claims sovereignty over the Himalayan region, citing dynastic tributes paid by Tibetan kings to the Ming and Qing emperors. The Nationalist forces though, which ruled China before the Communists, failed to impose their power over Lhasa and Tibetans lived in a self-imposed isolation until the annexation of their land by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1950.

In 1951, Chinese leader Mao Zedong signed a 17-point agreement with Tibetan rulers, according Tibet and its spiritual leader Dalai Lama special status. But the pledges of full autonomy and independent religious institutions embodied in the agreement turned out hollow. Tibetan resentment over China’s unfulfilled promises has smouldered ever since a failed uprising in 1959 forced the Dalai Lama into exile and allowed China to strengthen its grip over the land.

Over the years, Beijing has administered this restive mountainous area with a combination of state subsidies and tough measures aimed at stamping out the embers of resistance. "Tibet is crucial for the stability of the entire country and the security of Tibet is crucial for national security," said a hard-hitting editorial in the state-run Tibet Daily this week. "We will wage a tit-for-tat struggle and unswervingly fight back to quell the incident promptly and decisively."

Beijing sees Tibet as the frontline for China to enter Central Asia, West Asia and Indian Ocean, and has linked western support for the Tibetan cause to attempts to contain China’s expansion as a regional power. Prof Wang is affirmative of China’s success over the years in improving the material well-being of the Tibetan minority and obtaining its loyalty. He points to the opening of the first railway to Tibet in 2006, which has accelerated Tibet’s integration into the mainland economy and the movement of Han Chinese into the region. "I believe many Tibetan young people now recognise that their homeland’s potential for development lies with China," he says.

| Mao and the Dalai Lama in Beijing |

Fearing that Tibetan riots may set off a chain reaction of protests over a multitude of grievances harboured by ordinary Chinese people, top leaders have been careful to portray the riots as a plot aimed at the country’s sovereignty. No mention has been made of rights abuses or Tibetan grievances. State media reports have focused on horror stories related by Chinese inhabitants of Lhasa and omitted details of the crackdown and the deaths of 90 or more Tibetans. Premier Wen Jiabao has called the protests "an attempt to undermine the upcoming Beijing Olympics"—an implication that any unrest in the coming months that challenges the authority of the Communist Party would be treated as such.

Nearly 10 years ago, when China’s president and party chief Hu Jintao served as a party boss in Tibet, Tibetan protests were the first shot of an avalanche of demonstrations and unrest countrywide that culminated in the 1989 Tiananmen massacre. Then, as now, Beijing faced a volatile mix of social and economic woes—rampant corruption, inflation pressures and disgruntled peasantry. In 1989, China’s answer to people’s grievances was to order the PLA’s tanks in. Yet nothing has done more to blacken Beijing’s international image in the past 20 years than its suppression of the peaceful protests in Tiananmen.

(Antoaneta Becker is a Beijing-based journalist who has lived and worked in China for 20 years.)