"India has two weaknesses: a high current account deficit and the highest price earnings ratio in the world."

Adrian Mowat, JP Morgan

"Given how much the markets had risen, there's a lot of profit to be taken. There's no reason to panic."

Andrew Holland, Merrill Lynch

"The correction in the emerging market was not caused by the commodities correction at theLME."

Jim Rogers, Investment Guru

The Monday turned out to be manic. Panicked investors offloaded, stung traders and operators were forced to sell, foreign institutional investors continued with their "exit emerging markets" mood, and sentiments were at an all-time low. So was the Sensex as it plummeted over 1100 points—the biggest intra-day fall in the history of the Bombay Stock Exchange. Greed turned into dread, boom transformed into doom, and confidence was replaced by suspicion. Within a matter of two hours, the cleverly crafted and optimistic India story seemed like cheap pulp fiction.

On May 22, the sudden nosedive in the Sensex stumped everyone. There was bloodbath on Dalal Street. A more appropriate phrase would be the headline that was plastered across an economic paper a few days ago: Halal Street. The lambs, which had been fattened over 36 months as the markets zoomed to their historic highs, were slaughtered by the millions. No one, it seemed, would get out of this market unhurt. It was a classic case of how easy it's to lose one's shirt in a bull market. Blood pressures rose, and a few heart attacks seemed imminent.

Until, of course, the time when Union finance minister P. Chidambaram and the SEBI chairman, M. Damodaran, decided to hold the bears by their collars. During the one hour when trading was suspended on both the principal exchanges (BSE and NSE), they managed to calm down the nervous markets. The FM went a step ahead; he said both the FIIs and the domestic mutual funds were buying in this depressed market and, therefore, the retail investor should stay invested. Strong words they turned out to be; so what if some of them were lies. The data released by NSE the next day showed that FIIs were net sellers on Monday. But the markets recovered when trading resumed at 12.55 pm, and closed only 450 points lower from the morning's level.

But it seemed that a deeper, more macro story was unravelling as far as the Indian bourses were concerned. For, in two weeks since May 10, when the Sensex was at its highest ever at 12612 points, it had taken a battering of 16.5 per cent. The IFN India Fund, a popular fund traded on the New York Exchange, closed at $47.52 on May 23, down a much higher 26.5 per cent from its May 10 close. The popular and oft-quoted MSCI India Index was down 10.7 per cent between May 1 and May 23, although it was up 11.6 per cent from its level at the beginning of the year.

Does it imply that the Indian party is over? More importantly, is the India story still intact? And, as investors are asking, is it the beginning of the end?

Chidambaram thinks the answer is a categorical 'No', for, the Indian fundamentals remain unchanged. Economic growth was expected to be high, manufacturing was steaming ahead, inflation was low, forex reserves were bulging, corporate earnings were in line with expectations. He told a TV channel that there was nothing to worry for genuine investors because they were invested for the long term and the long-term India story continued to be that of solid growth. No one, he added, has doubted India's growth story. "I would say crash is an inappropriate word (to use) because it suggests that you cannot drive away from it. But I think India will be able to drive away from this quite well," says Adrian Mowat, chief Asia strategist, JP Morgan.

So, what happened in those days? Why did the markets tank? Numerous global factors and the new investors' mindset of booking profits at the slightest tremor have made the markets extremely volatile. Not just in India, but in most of the other emerging markets. So, we have come a long way from an era when the markets consistently and confidently discounted any bad news—be it the tsunami or the Mumbai floods—to one where it will overreact on the slightest of bad news, even if it's in the form of rumours and gossip.

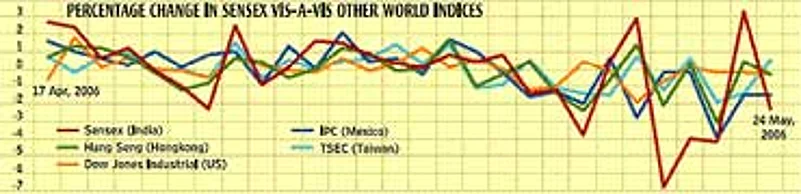

In this case, there were fundamental shifts happening under the surface. Slowly, quietly, but steadily, the FIIs began withdrawing from the emerging markets. Before the current correction, emerging markets and the so-called BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) were riding the wave of unprecedented foreign inflows. BRICs and emerging markets funds were on a high and over $71 billion dollars were estimated to flow into emerging markets this year in terms of portfolio investments. But suddenly, the bottom caved in. As on May 23, Brazil's Bovespa was down 13.5 per cent, South Korea's Kospi 8.1 per cent, Russia's rts 25 per cent and the Indonesian index 13.8 per cent. FII outflows have dragged down other markets too. MSCI's BRIC index is down 9.7 per cent since May beginning, while its emerging markets index is down 8.3 per cent.

At a factual level, there was a constant stream of negative global news. Sure enough, on May 10, US data showed that inflation rates in the country were higher than expected, leading to fear that a new interest rate hike might be on its way soon. In the past, the US Fed has hiked rates by 0.25 per cent for sixteen consecutive quarters, raising it to 5 per cent. This triggered a sell-off in emerging markets as global investors prepared for a liquidity squeeze in the near future. When interest rates go up in the US, most of the FIIs retreat to invest in safer American markets.

In fact, FIIs withdrew a net of Rs 5,967 crore between May 12 and May 23 from the Indian markets. It really started on Friday, May 12, when the Sensex closed 150 points down as FIIs sold shares worth Rs 1,199 crore. By Monday (May 15), these figures were released and further dented market sentiments, and the Sensex fell by 450 points in response. Although Andrew Holland, head of the Strategic Risk Group, DSP Merrill Lynch, says this needs to be seen in the context of the foreign inflows of $4 billion this year itself, investors viewed it differently.

They were further convinced something was amiss after the crash in metals prices on the London Metals Exchange (LME) the same day (May 15). It prompted investors to wonder whether the run-up in the global commodities market had indeed been a bubble. Indian metals stocks, including TISCO, Hindalco, SAIL and others, also crashed, further pulling down the Sensex. By the end of that week, the Sensex shed 11 per cent, but the BSE metals index lost a much higher 22 per cent. It signalled the beginning of the panic. On Thursday (May 18) and Friday, the Sensex was down nearly 1300 points.

Global investment guru Jim Rogers has a different take on the events. "I have been saying that the Indian markets were overheated and needed a correction. The stockmarket correction (in emerging markets) was not caused by the commodities correction (at the LME). Stock prices were stretched anyway. India, and other emerging markets including Russia and Turkey, fell, causing the commodities prices to go down too," he explains. And he adds that one should always be wary when hordes of FIIs enter a particular market as they are finicky. "They rushed into India thinking it was the new promised land. Then they realised it wasn't," he adds.

His sentiments are accepted by several others, albeit in a subtly different way. "With everything up, something had to give," says Holland. He was among the analysts whose end-2005 reports had predicted that the Sensex would touch the 10000 mark by end-2006. When that happened in February 2006, they revised the reports to talk about 12000 levels by October this year. That mark was breached in May itself. It was around the same time that investment bankers like JP Morgan and others felt that a 4-5 per cent correction in the Sensex was long overdue.

The old solid optimism took a beating as the Sensex giddily zoomed 35 per cent between January and early May. Suddenly, there was this unreal feeling about the ongoing party. When the Sensex was at 6000, there were enough investors who believed it would go up to 8000. It did and then there were still many who believed in the 10000 levels. Even at those high levels, there was a genuine feeling that 12000 was achievable. But once that happened, the institutional investors were cagey of predicting even higher levels. That's when many took a short break and global factors merely added to this unease.

"I do not believe that a major structural break has taken place during the past two weeks in the behaviour of foreign investors in emerging markets, like India," says Andrew Karolyi, Charles Webb professor of finance at the Ohio State University. He adds that "we are unlikely to see any kind of 'financial contagion'. It is not a shift in their (FIIs') risk aversion, as much as a pause as they reassess the risks." But Tony Dolphin, director of economics and strategy at Henderson Global investors, added a twist to it in a report titled 'What's upsetting equities markets?' According to him, "Big risks in commodity prices and exchange rates make the world seem a riskier place. As a result, some investors may be looking to lighten up their position in risky assets—including equities—causing their price to fall."

"Perhaps the excessive love for risk has passed," said Rodrigo Azevedo of the Brazilian central bank. So, spending has become more risky and, therefore, investors have scrambled to cut down their risks. In the case of India, says Mowat, "People want to take risk off the table and India has two weaknesses. It has a high current account deficit and price earnings ratios are among the highest in the world." Indian stocks, according to Bloomberg estimates, are trading at a price earnings ratio of 17.5 compared to 12 for other emerging markets on the MSCI.

In such a scenario, expensive commodities and emerging markets would be the first casualties. Just as emerging markets did not know what hit them when record foreign inflows came in, they were now stranded as flows ebbed out due to several realistic and sentimental factors. No one could immediately explain how things had changed in a few days' time.

One reason that explains this was the increasing component of 'hot' money that has flowed into Indian equities. According to SEBI figures, nearly half of the foreign inflows have come through the opaque participatory notes (PN) route. PN is the mechanism through which FIIs can invest monies that's come from third-party sources in emerging markets. An internal finance ministry report mid-last year speculated whether the PN route was used to channelise money from illegal and questionable sources, apart from hedge funds, into the Indian markets. This is the kind of money that's always seeking the next big wave, and flies out of any markets in a jiffy. In fact, hedge funds are said to have been among the biggest sellers during this correction.

A second reason could be that it suddenly made the genuine FIIs a bit careful. A Mumbai-based FII fund manger admits he hasn't been investing over the past few weeks. He has just been waiting for the market to stabilise a bit, and get an idea of what direction it's likely to take, before he entered the market again. Others too contend they're waiting for the Indian markets to stabilise and bottom out. And once the global factors and the changing investors' attitude triggered a fall, the fear that the big correction hadn't yet played out took on a life of its own. "It was a correction on technical issues," says C.J. George of Geojit Securities.

On the one hand, most of the retail investors, small operators, day-traders and sub-brokers followed FIIs' cues and decided it was time to book profits. They began to sell at the first sign of the coming correction. When the Sensex tumbled on Thursday (May 18) by over 800 points, they joined the herd in hordes. By Monday (May 22), they were willing to sell at any price. They didn't want to be the ones to be hurt, as had happened to them in all the previous busts. And they did, causing the Sensex to go into a free fall.

On the other hand, most of them felt there was no way the markets could go down and, hence, had built up leveraged long (buy) positions. For them, the Monday (May 22) fall started a process of margin calls. Under the new market regulation, brokerage houses have to settle their trades by next morning. Or ask the investors who trade through their terminals to cough up the margins to continue with their positions in the futures and options market. In a rapidly falling market, the margin requirements shoot up instantly. And the small investors find it hard to pay up.

For one, even if customers have the money, they find it difficult to pay the extra sum so soon unless they make the payments online. But that forms a small portion of the transactions. Faced with a liquidity crunch at settlement times, brokers have to forcibly sell shares of their clients to square off positions. That's exactly what happened on Monday. Several Mumbai-based brokers confirmed they had been caught in a bind and had to force customers to sell. Others stopped trading for a while or closed down a few of their terminals.

In such uncertain times, rumours and gossip suddenly turn larger than life. They cajole, they force, they push the common investors to get out. And that happened in those three crazy trading sessions (May 18, 19, and 22). First, on Thursday, it was the news that the government was planning to treat FIIs as traders, and not investors, and tax their earnings. Despite Chidambaram's clarification the same evening, things didn't improve as the Sensex fell the next day too. It was left to the FM to reclarify the position thereafter.

On Monday (May 22), another piece of information was floated on the grapevine. It was believed that there was a major payment crisis on the two exchanges (BSE and NSE). Brokers, operators and speculators were unable to fulfil their margin commitments and a crisis was looming. During the one-hour suspension in trading, Chidambaram and Damodaran clarified that this was not the case. Both maintained that systems were in place and everything was normal. The same day, the exchanges stated that all payments for Thursday had been settled. In retrospect, even Monday's transactions were settled smoothly.

Although Chidambaram blamed the fall in the markets on these rumours, others weren't sure. The latter thought that the grapevine only aided the fall, which was due to other global and technical factors. There was a method to the madness even though many didn't see it that way then. Market volatility has a basis, whether sentimental or factual. In the past two weeks, it was a combination of both. Analysts add that bounty-laden monsoon clouds hovering over Dalal Street and elsewhere in the country will lead to strong corporate results. And that will ease most of the worries on investors' minds. "Given how much the Indian markets had gone up, there's a lot of profit to be taken. But there is no reason to panic yet," advises Holland.