Storage Spaces

- SCTR scans, edits, digitises cultural, literary manuscripts, music, other reference tools

- Conducts studies in history of printing, recording of oral literature

- Archives include works of noted Bengali writers as well as genres like early Bengali drama, and Hindustani classical music

- Certificate course in editing, publishing; doctoral research; short-term training courses, and music appreciation

***

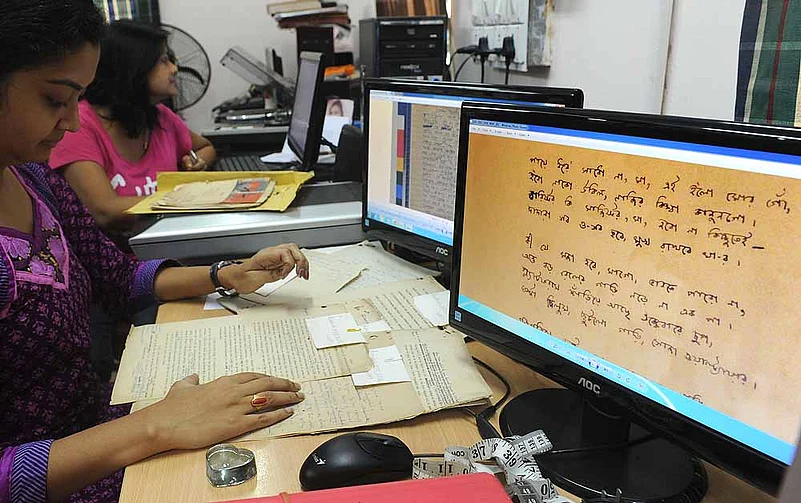

At the end of a third floor corridor in Jadavpur University’s Arts building there is a department of English room where, ten years ago, a movement began—a crusade against time’s inexorable march. No, they have not quixotically endeavoured to stop time in its tracks. What they have been able to do is reverse the ravages it wreaks in its wake. That, after all, is the declared telos of the School of Cultural Texts and Records (SCTR), one of JU’s non-degree projects. It ferrets out mouldering, unpublished manuscripts of noted authors and poets from the dusty shelves of oblivion, and preserves them using a variety of methods, mainly through digitisation. SCTR’s work also involves scouring private collections of music so that priceless content captured in the decaying and friable—cassettes, long-playing records, even spools—may be saved using time-defying technology.

“There is a vast body of unpublished written work by distinguished authors, which is in danger of being lost forever unless something is done to preserve them,” Professor Sukanta Chaudhuri, founder of the school, explains. “Most of the written work, while in the safekeeping of family, friends, relatives or other private collectors, and undoubtedly treated with the utmost care, is nevertheless subject to time’s natural decay.” They are mostly hand-written in ink that fades with time, on paper that rots with each passing day. And the manuscripts exist in myriad forms—diaries, notebooks, loose sheafs, even scraps of paper stashed or filed away in cupboards of private homes or libraries.

In fact, it was the discovery of four such tin trunks containing the unpublished, private papers of eminent modernist poet Sudhindranath Datta and his wife, singer and musicologist Rajeshwari Datta, which came as the impetus to begin such a project. “Sudhindranath and Rajeshwari Datta, who had a long and close association with Jadavpur University during their lifetime, had bequeathed the body of their unpublished work to the university and therefore issues such as copyright did not pose a problem,” says Chaudhuri. “So we could immediately begin”.

Other works started trickling in, then came in a flood. “We have been very lucky,” says Professor Amlan Dasgupta, director of SCTR. “We have never really had to cajole or coax anyone for the salvaging or obtaining of documents or music. Friends, family and other custodians have mostly entrusted us with the material voluntarily.” Dasgupta, a connoisseur of music, spearheaded the school’s music preservation project at the time of its inception. If in the initial stages, those in possession of the documents did harbour some apprehensions, the reputation of the founders and faculty won them over.

Damayanti Basu Singh narrates the sequence of events which finally convinced her to hand over the manuscripts of her illustrious father—author Buddhadeva Bose—to the school. “I knew Sukanta and trusted him. Then I had to convince my mother and elder sister, who had equal say over the matter. But we had one condition. We didn’t want the manuscripts to go out of our hands. Sukanta understood my fears. Even if one page went missing it would be a terrible loss. So it was agreed that someone would come to my house with a portable scanner at a designated time and make copies. This continued for some time. But, gradually, the timing began to be a problem. After a while I agreed, after Sukanta assured me, to let them take four or five manuscripts at a time, process them, return them, then take the next lot.”

In 10 years, Damayanti feels “the school is doing excellent work in retrieving the manuscripts of authors who live on through their work beyond their lifetime”. In fact, it was she who in turn went on to encourage Meenakshi Chattopadhyay, wife of cult poet Shakti Chattopadhyay, to let SCTR have the manuscripts of her late husband.

Since those early days, the school has come a long way, added layers to its work and dealt with more complex issues than just digitisation of manuscripts and analogue music.

“We have gone beyond salvation and preservation to create an archive of an author’s entire body of work so that it becomes a one-stop reference point for researchers and others,” explains Dasgupta. This includes the complete works of Rabindranath Tagore, which, with its 14,000 pages, is arguably the world’s largest single-author archive. “Today, if your subject of research is Tagore and if you want to see the entire body of Tagore’s works (manuscripts) contained in one space, you no longer have to hop from Rabindra Bhavan to Harvard University to the National Library—places where the vast body of his work had earlier been housed in parts. Now, you can come to the school and sift through it in its entirety,” says Dasgupta.

The school has also introduced a number of vocational training courses, including a certificate course in editing, publishing and printing, short-term training courses in bibliography, documentation and textual research, including the use of electronic resources. It also has a doctoral programme which enrols students for research on SCTR’s field of activities and an audit course on music appreciation. “There is a great deal of interest in these courses,” points out Abhijit Gupta, faculty member, SCTR. One reason for that is Jadavpur University’s policy of keeping fees low—SCTR courses do not cost more than Rs 6,000.

At the moment, it is Jadavpur University students who primarily form the group of research scholars at the school. Six faculty members, also from JU (including Dasgupta and Gupta), give lectures, though guest and visiting lecturers frequently address special sessions. As far as funding is concerned, SCTR—which took root around when JU had won a UGC grant under the ‘university for potential of excellence’ category—has in its ten years received some of the most prestigious grants from across the world.

However, lack of funds is what Dasgupta cites as the school’s biggest drawback right now. It’s a signifier of the times that even a project that aims to conserve literary and musical heritage has to apply for funds. “We go online and apply,” says Dasgupta. At the same time, the SCTR, in deference to old-world (some would say hopelessly idealistic) notions of scholarship, will not charge scholars, researchers or even the general public any fee for visiting and using their archives.

(Applications for this year close on June 30. Visit bichitra.jdvu.ac.in)